| + |

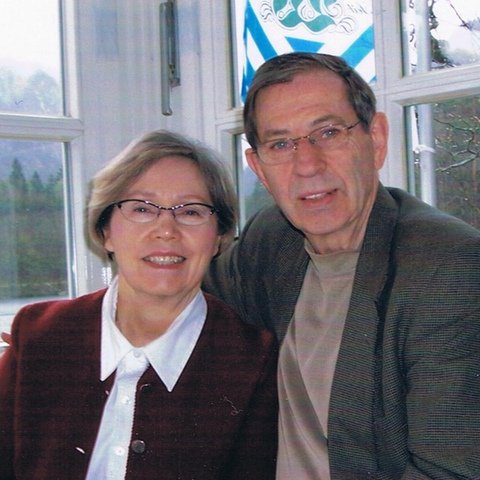

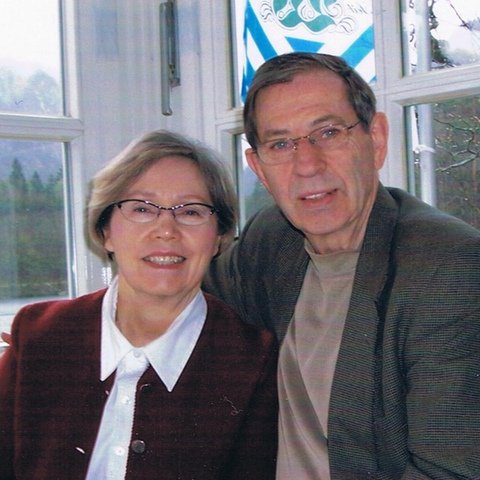

Visiting Mennonites

|

November 15, 2012

|

Vol. 4, No. 6

|

This issue offers three essays by and about three writers who have spent significant time with Mennonites, and features work by Abigail Carl-Klassen, whose poems about the Mennonites in Texas and Mexico are based on observation and oral histories. |

by Ervin Beck

This issue was inspired by Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift’s …

|

by Ervin Beck

The Reading at Goshen College

It was a dark and …

|

by Ellah Wakatama Allfrey

I came to Goshen, Indiana, in the winter of 1987. …

|

by Emma LaRocque

My connection with Mennonites goes back to my early teen …

|

by Abigail Carl-Klassen

The following poems are based on my experience and observations …

|

|

read more from Visiting Mennonites

|

|

| + |

Documentary Film

|

September 14, 2012

|

Vol. 4, No. 5

|

Documentary Filmmakers write about their work. |

by Ervin Beck

Documentary film is the creative nonfiction genre in the cinematic …

|

by Burton Buller

“The movie is the rival of schools and churches, the …

|

by David Dueck

Like the rest of my Mennonite Brethren Church congregation in …

|

by Paul Hunt

I had just returned from filming a family of seven …

|

by Dirk Eitzen

I might as well say that right up front, for …

|

by Jay Ruth

I have worked at video production since 1985, almost all …

|

by Burton Buller

|

by David Dueck

|

by Paul Hunt

|

by Dirk Eitzen

|

by Jay Ruth

|

|

read more from Documentary Film

|

|

| + |

Mennonite/s Writing VI

|

August 4, 2012

|

Vol. 4, No. 4

|

A sampler of creative writing from Mennonite/s Writing VI: Solos and Harmonies, held at Eastern Mennonite University March 29-April1, 2012. |

by Ann Hostetler

In this issue is a sample of original creative writing …

|

by Anita Hooley Yoder

I was introduced to Sleeping Preacher as a first-year student …

|

by Anita Hooley Yoder

Four poems Anita read at the conference, two of them …

|

by Jesse Nathan

"Permission" was inspired by Jesse's experience at Mennonite/s Writing VI; …

|

by Connie T. Braun

Author's note: In these poems the speaker is generationally, linguistically …

|

by Becca J.R. Lachman

These new poems read by Becca at the conference grow …

|

by Maria Lahman

Author's Note: I formed this research poem from in-depth interviews …

|

by Kristen Mathies

This short story, read at the conference, was inspired by …

|

|

read more from Mennonite/s Writing VI

|

|

| + |

Embodiment - The Shenandoah Valley Inkslingers

|

May 16, 2012

|

Vol. 4, No. 3

|

We have chosen the theme Embodiment for the Shenandoah Valley Inkslingers edition of the Journal of the Center for Mennonite Writing. It’s a fitting theme for a Mennonite publication; an outsider reading the Mennonite Confession of Faith might be excused for believing that she now knows who Mennonites are, but those of us who are from, within, or near Mennonite communities know that enormous portions of Mennonite identity are tangible and irreducible: cooking, relief work, farming, bloodlines, schisms, and singing in harmony, to name a few manifestations of this embodied faith and culture.

In Kirsten Eve Beachy’s essay, tending to students’ physical hunger opens her to the possibility of a more visceral approach to teaching. Pam Mandigo’s play deals directly with the body—that is, bodies and the grave-diggers who bury them—and in this excerpt, the character Tom Wheeler’s troubles are embodied as the monster that pursues him. Jessica Penner’s essay about amputation explores disembodiment, and the way the body clings to its wholeness even after her fingers are severed. A myth of incarnation, shared between two characters in sign language, is Tonya Osinkosky’s contribution. Anna Maria Johnson describes how dance gave her permission to inhabit her body and became a way to be present with others in grief. The next essay, by Andrew Jenner, probes the ways the mind limits the flesh as it describes the experience of living inside one particular body. In Chad Gusler’s short story, miraculous signs herald a young writer’s inspiration. The closing piece by Alisha Huber celebrates books as physical containers for words and bodies as containers for the Word.

We are young writers, but when we gather as a body for our rituals of eating, laughing, critiquing, and sharing, we grow into our identities as authors, and we revel in the pleasure of being writers-with-writers. Andrew Jenner has compiled a Q & A with our group that further describes our process and history. -- Kirsten Beachy, May 2012 |

by Kirsten Beachy

If I had grown in some generous place—

If my …

|

by Pam Mandigo

The Characters

TOM… a man with a monster

AMELIA… his …

|

by Jessica Penner

The scent of a pre-op is unmistakable: rubbing alcohol, plastic, …

|

by Tonya Osinkosky

In this excerpt, Jesus (from Guatemala and who came to …

|

by Anna Maria Johnson

A story circulates throughout my extended family about the time …

|

by Andrew Jenner

Since you ask so intently, I’ll be frank. I do …

|

by Chad Gusler

Lenore was happy to sever her friendships. It’s for a …

|

by Alisha Huber

Some orthodox Jews kiss every book before they open it. …

|

by Andrew Jenner

How did you come to join the group?

KB: Chad …

|

|

read more from Embodiment - The Shenandoah Valley Inkslingers

|

|

| + |

New Fiction 2

|

March 16, 2012

|

Vol. 4, No. 2

|

One mission of the Journal of the Center for Mennonite Writing is to offer a forum for the publication of writing by emerging authors whose work has not otherwise gained the attention of many Mennonite readers.

This issue, “New Fiction 2,” extends the work of the “New Fiction” issue of January 2010 by publishing the work of six “new” writers. Only one author, Katherine Arnoldi, has already had a book of stories published, All Things Are Labor, by the University of Massachusetts (2007). In fact, her story published here, “Sewer,” serves as a kind of prequel to that collection, since it depicts the early life of the woman whose voice dominates the first and final narratives in All Things Are Labor.

Kirsten Beachy has become a leader of young Mennonite writers in the eastern United States, especially with her excellent and expeditious work in gathering and editing the contributions to the anthology, Tongue Screws and Testimonies (Herald Press 2010). Her story, “His Wife,” is the most experimental in this issue, since Kirsten writes minimalist, rather than expansive, narratives. As she explains, “Forty gallons of maple sap distills to a gallon of syrup. In my reduced stories, I try to save the essence and let the steam blow away.” Considering the complexities of her story, you may need to read between the lines. Kirsten contributed a memoir on Martyrs Mirror to the “Personal Writing” issue of this journal (September 2009).

Kirsten is also a main organizer of the Mennonite/s Writing conference scheduled for later this month at Eastern Mennonite University. (See the link on the CMW homepage.) In fact, all of the contributors to the issue—except for Matt Kauffman Smith in faraway Oregon—plan to attend the conference, and new writings by Arnoldi and Sears will be featured in public readings. Kirsten’s writing group Inkslingers are also on the program. Selections from their writings will constitute the May 2012 issue of the CMW Journal.

Five of the six stories are told from a woman’s point of view. Chad Gusler even uses the voice of a blunt-speaking woman who is a Mennonite former pastor addressing a Jewish former husband. Kirsten’s story and Jennifer Sears’ chapter for a novel depict cross-cultural situations, from Egypt and Pakistan. It is tempting to assume that some or most of the narratives, especially those told in first-person, come from the authors’ own lives. However, Kirsten has never been to Pakistan and Beth Lehman’s story was inspired by a submerged bicycle that she noticed during her recent years in Indianapolis. The story by Matt Kauffman Smith, who also has a memoir in our January 2012 issue, contributes his sly, laconic humor to an otherwise rather sober issue.

As editor, I am pleased that, without planning, all of these short stories were written by Mennonite writers living and working in the United States. It remains true that, although poetry has been well cultivated by U.S. Mennonites, fiction has remained less well developed among them. Perhaps issues like this will help improve that situation.

I am very sorry that it was not possible to include new fiction by Stephen Raleigh Byler, whose recent serious injuries from an automobile accident made it impossible for him to follow through with our plans. I expect to read a paper on his book, Searching for Intruders: A Novel in Stories, at the upcoming Mennonite/s Writing VI conference at Eastern Mennonite University. In preparing the paper, I also wrote the essay that concludes this issue, “The Mennonite Novel-in-Stories: A Survey.” Besides briefly describing the sub-genre and its history, the essay offers an annotated critical bibliography of collections of short fiction with novelistic tendencies, written by Mennonites. I hope the essay will both enhance our appreciation of writings by Byler, Rudy Wiebe, Armin Wiebe, Sandra Birdsell, Rosemary Nixon and others and lead to further study of their linked short stories. |

by Jennifer Sears

In the wake of the policies put into place after …

|

by Kirsten Beachy

On the counter is the new toy that Donald accidentally …

|

by Ervin Beck

In the production of Mennonite literature in North America since …

|

by Chad Gusler

Before I tell you that I know all about Maria …

|

by Katherine Arnoldi

First I heard the meow. Loud. Frantic.

I walked around …

|

by Beth Lehman

As soon as the last ripple made its way to …

|

by Matthew Kauffman Smith

Winnie Weaver reached for a hymnal and looked over at …

|

|

read more from New Fiction 2

|

|

| + |

Memoir

|

January 15, 2012

|

Vol. 4, No. 1

|

The memoir and creative nonfiction issue for 2012. |

by Ann Hostetler

Memoir has come of age in Mennonite literature. Family history, …

|

by Matthew Kauffman Smith

On the first day of school in 1984, I planned …

|

by Eileen R. Kinch

All around me was a familiar sea of Plain people. …

|

by James C. Juhnke

In the spring of 1942, not long after my fourth …

|

by Loretta Willems

I had just left the ranch that Stanley and I …

|

by Peter Miller

Lyric poetry can feel at home among prose memoirs. Both …

|

by J. Daniel Hess

To clarify what I mean by memoir as a “troubled …

|

|

read more from Memoir

|

|

| + |

College Student Writing 2011

|

November 16, 2011

|

Vol. 3, No. 6

|

In this issue readers will find four personal essays on growing up Mennonite by Goshen College students and a selection of poems from a first year student at Notre Dame University. Also included is a review of the critically-acclaimed drama “The Lamentable Tragedie of Scott Walker,” written by Doug Reed (Goshen College alum 1990), currently in its second run in Madison, Wisconsin. |

by Sara Wakefield

The idea for a journal issue devoted to writing by …

|

by Phil Weaver-Stoesz

When you’re growing up, the thing about water guns is …

|

by Kate Stoltzfus

I can clearly remember the moment I turned into a …

|

by Sarah Rich

I grew up in one of those college-professor neighborhoods where …

|

by Annie Martens

“Eliiijah,” I whined, “Can I play?”

“You don’t know how …

|

by Vienna Wagner

The poem, "Esther," published here, won a special merit award …

|

by Vienna Wagner

Shiva balances on a window

ledge where sunlight stretches to …

|

by James C. Juhnke

Based on attendance at the drama September 2 and an …

|

|

read more from College Student Writing 2011

|

|

| + |

The Poetry of Peace

|

September 11, 2011

|

Vol. 3, No. 5

|

On the 10th anniversary of 9/11 we offer an issue co-edited by Jeff Gundy and Ann Hostetler to commemorate a decade of peacemaking and peacbuilding. The poems and essay collected here, with commentary by the writers, express a range of voices attuned to the delicate and complex work of peace as both an interpersonal and cross-cultural endeavor. The issue closes with a meditation on William Stafford, a poet dedicated to peace, in the form of a sermon delivered by Jeff Gundy at First Mennonite Church in Bluffton on 9/11/2011. |

by Jeff Gundy

Every Mennonite poet I know is an ardent peacemaker—and so …

|

by Ann Hostetler

On September 11, 2001, I was co-teaching a Humanities Lab …

|

by Alicia Ostriker

The prophet Isaiah tells us that some day people "will …

|

by Julia Spicher Kasdorf

"We are against war and the sources of war. We …

|

by Jean Janzen

In a poetry workshop years ago I was taught to …

|

by Yorifumi Yaguchi

During the Second World War, I as a child experienced …

|

by Keith Ratzlaff

Like many of my generation of Mennonites, my introduction to …

|

by Barbara Nickel

Peace is shattered. Years later, a small poem comes unbidden, …

|

by John Paul Lederach

A brilliant artist once said blessed are the peacemakers. …

|

by Michelle Webster-Hein

Shortly after September 11th, 2001, when I was a 21-year-old …

|

by Jeff Gundy

Sermon given at First Mennonite Church, Bluffton, Ohio, 9/11/2011

|

|

read more from The Poetry of Peace

|

|

| + |

Drama

|

July 15, 2011

|

Vol. 3, No. 4

|

July 2011 |

by Ervin Beck

The early suspicion of drama, theater and film by Mennonites …

|

by Vern Thiessen

Copyright © 2011 Vern Thiessen

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A ten-minute version of …

|

by Don Yost

Copyright (c) 1982 Donald C. Yost

Based on interviews by …

|

by Talia Pura

The Moonlight Sonata of Beethoven Blatz had its world premiere …

|

by Lauren Friesen

The playwright, poet and novelist Hermann Sudermann was …

|

by Lauren Friesen

July 2011

I. PLAYS

A. Collected plays:

Hermann Sudermann. Dramatische …

|

by Ervin Beck

About 15 kilometers south of the birthplace …

|

|

read more from Drama

|

|

| + |

Literary Art in Worship

|

May 16, 2011

|

Vol. 3, No. 3

|

In This Issue

For the past few decades, writers from Mennonite contexts have been receiving recognition from the literary world for their poems, stories and plays. But what of the reverse—is there a place for literary art in Mennonite places of worship? What are the possibilities of bringing home the work? Certainly not every literary work belongs in worship, but opening a space for literature in worship can open new possibilities for participation and meaning. In this issue we hear from a literary scholar, a pastor, several poets, and two seminary professors who reflect on the meaning of words in worship.

In the fall of 2004, I went on an east coast reading tour for A Cappella: Mennonite Voices in Poetry with poets Di Brandt and Julia Spicher Kasdorf. One of our readings took place at the 15th Street Friends’ Meetinghouse in Manhattan, graciously hosted by Malinda Berry, a student at Union Theological Seminary at the time. After we each read poems from the anthology, we turned to the audience and invited anyone who had brought poems to an open mic reading. One young woman had just come from a creative writing class. She had not intended to read, but was persuaded to share her reflection on her grandmother’s hands with us. In the flickering candlelight we imagined with her the polished wrinkles, the tender skin of these hands marked by work and care. Afterwards she made the comment, “I didn’t know that poetry could be read in church.” At that moment, I decided that I would direct some of my energy towards bringing back the gift of poetry to the community that had nurtured the poets. I didn’t want to have such talented writers believing that their art could only flourish outside the church. This issue is a fruition of that desire to bring the words back into the space in which we honor the Word and source of creativity.

Sheri Hostetler’s essay, “Poetry as Contemplation,” was written a number of years ago in response to a call for essays from the poets in the anthology A Cappella: Mennonite Voices in Poetry. The final version of the anthology did not include the essays, but the language and phrases of Sheri’s essay stayed with me and I found myself quoting it in several of my own talks and articles. I am pleased that her essay, revised to incorporate her path from poetry to pastoring, has found a home in print in this issue. Sheri is also a fine poet, and in addition to the poems published in A Cappella—some of which have found their way onto Garrison Keillor’s "The Writer’s Almanac"—she has written poetry for worship. Several of these poems, along with a description of the writing prompts that created them, are also published here for the first time. I hope this will inspire more worship teams to include creative writing in their services.

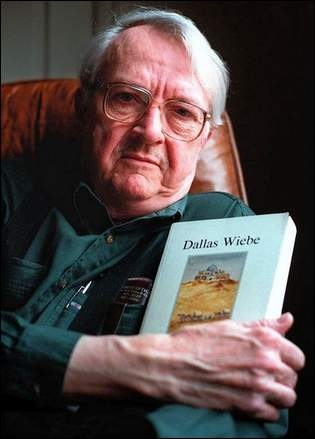

Dallas Wiebe, a seminal voice in Mennonite Literature, known primarily as a novelist and short story writer, turned to poetry at the end of his career and published several startlingly powerful volumes on religious themes: On the Cross (Cascadia 2005) and Monument: Poems on Death and Dying (Sand Hills 2008). Hildi Froese Tiessen’s essay about her experience of incorporating Wiebe’s poetry into worship illustrates the ways in which poetry can serve to open up new possibilities for honesty and connection. Three of Wiebe’s poems, chosen from Monument by Froese Tiessen—who is also one of its publishers—are reprinted in this issue.

Malinda Elizabeth Berry and Rebecca Slough both reflect on the role of literature in worship from theological perspectives. Berry, Director of the M.A. Program at Bethany Seminary in Richmond, Indiana explores the potential she sees for literature to play a role in the regeneration of Anabaptist theology. Aware of the complexity and interpenetration of religious, cultural, and artistic symbols, she concludes with a layered image of the cross as interpreted by Toni Morrison. In her essay, “What Language Shall We Borrow,” Rebecca Slough, Dean of Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary in Elkhart, Indiana, brings us back to the “Word” and reminds us that in a worship service rooted in scripture, hymns and poems can complement and deepen our reverence for the Word. Her essay offers strategies for renewing our relation to words, and will be of especial value to those who attend to the Word as they select complementary texts for worship.

Finally, A Cappella: Mennonite Voices in Poetry (Univ. of Iowa 2003) remains an excellent source of poems for worship, and many of the writers anthologized in that volume have gone on to publish new books, some of theological interest, such as Jean Janzen’s recent Paper House (Good Books 2010) and Todd Davis’s The Least of These (Univ. of Michigan Press 2010). Cascadia Publishing offers a number of poetry books under their Dreamseeker imprint that are good sources for worship poems, including Cheryl Denise’s I Saw God Dancing, Shari Wagner’s Evening Chore, and Dallas Wiebe’s On the Cross. Other poets whose words often find their way into worship include Wendell Berry, John Donne, T. S. Eliot, Gerard Manley Hopkins, James Weldon Johnson, Mary Oliver, William Wordsworth—just to name a few. |

by Sheri Hostetler

My journey as a poet began the day I discovered …

|

by Sheri Hostetler

An Advent worship leader at First Mennonite Church of San …

|

by Hildi Froese Tiessen

I was born to be a shepherd. I was trained …

|

by Dallas Wiebe

From Monument: Poems on Aging and Dying

Reprinted with permission …

|

by Malinda Elizabeth Berry

I have been living, studying, and working in a seminary …

|

by Rebecca Slough

Worship is a public event in which a group of …

|

|

read more from Literary Art in Worship

|

|

| + |

German Scholars on Canadian Mennonite Writers

|

March 16, 2011

|

Vol. 3, No. 2

|

In this Issue

We are pleased to publish three essays by German scholars on Canadian Mennonite writers, along with a poetry feature by American poet Katie Lehman Pierce.

This group of essays engages issues of language and translation in complimentary ways. Wolfgang Hochbruck’s essay, “Rudy Wiebe’s Reconstructions(s) of the Indian Voice,” articulates three approaches to representing the multiple voices and languages of First Nations Canadians in Wiebe's fiction. This essay, originally published in France in 1989, takes on new relevance with the recent publication of Rudy Wiebe's Collected Stories: 1955-2010, which reveals Wiebe's full contribution in this genre. Martin Kuester’s overview of recent Canadian Mennonite literature, “A Complicated Kindness—The Contribution of Mennonite Authors to Canadian Literature,” raises the question of whether Canadian Mennonite writers owe some of their versatility and creativity to their multilingualism. Many of these writers have a background in Plautdietsch and German in addition to English, and perhaps hear these different “voices” as they compose their work. Christoph Wiebe approaches Miriam Toews’ A Complicated Kindness from a theological perspective in “’The Tail End of a Five-Hundred-Year Experiment that has Failed: Love, Truth, and the Power of Stories in Miriam Toews’ A Complicated Kindness.” As the pastor of the Krefeld Mennonite Church, one that has been in existence for 400 years without a split, he urges theologians to listen to the voices emerging from Mennonite literature. The essays by Kuester and Wiebe were translated from German into English by Gerhard Reimer, an American scholar and professor of languages who grew up as Mennonite in Manitoba.

Alongside these significant contributions to the criticism of Mennonite literature scholarship, we feature an American poet new to readers of Mennonite literature: Katie Lehman Pierce. Several of her poems published here have been inspired by Katie’s residence in Ireland, where she worked and studied with an Irish nun. Thus the works in this issue involve questions of transatlantic travel and translation—in terms of both culture and language.

We hope these works will lead to a deeper appreciation of the linguistic heritage of Canadian Mennonite writers, and the role that cultural exchanges play in contemporary literature by writers of Mennonite heritage. Look for a review of Rudy Wiebe's Collected Stories in an upcoming issue of the Journal.

Ann Hostetler and Gerhard Reimer, co-editors |

by Martin Kuester

Introductory presentations on the topic of Canada, Canadian studies and …

|

by Katie Lehman Pierce

Garden Talk

In western Connemara, County Galway, Ireland, a Victorian …

|

by Wolfgang Hochbruck

This essay originally appeared in RANAM: Recherches Anglaises et Nord-Américaines …

|

by Christoph Wiebe

Translated from the German by Gerhard Reimer

|

|

read more from German Scholars on Canadian Mennonite Writers

|

|

| + |

Indianapolis Writers Group: On Mennonite Identity

|

January 15, 2011

|

Vol. 3, No. 1

|

In This Issue

About every sixth Saturday morning, five writers gather around a cozy breakfast table in an Indianapolis home to eat, discuss current events and read to each other our most recent writings. J. Daniel Hess, retired professor of communication at Goshen College, pulled us together about ten years ago in order to encourage creative writing. Admission to the group was not based on prior writing experience or success, but simple desire. We quickly discovered a comfort level with each other that has allowed for honest, personal and insightful conversation—as well as invaluable feedback.

Our occupations vary: a poet, pastor, professor, psychiatrist and physician. Some of us have published essays or books, stories or poems; others of us have not. But at the breakfast table we are equals, eager to listen and share. Our time together has inspired us to write more—and better—than we would have done alone.

Recently we found ourselves discussing Rhoda Janzen’s Mennonite in a Little Black Dress, which in turn led us into a discussion of what it means to be Mennonite. Each of us understood, and had experienced, being Mennonite in significantly different ways. Having already been invited to create the contents for this issue of CMW Journal, we had a sudden “aha” moment—we would use Mennonite Identity as our common theme.

In this issue—through personal essay, memoir and poetry—we explore the twists and turns, the obstacles and landmarks, that have contributed to, and helped us define, what it means for each of us to be Mennonite.

J. Daniel Hess starts us off with an intriguing autobiographical essay, “My Mennonite Identity,” which describes his journey from a conservative Mennonite home with a thick Pennsylvania heritage, to going off to a more open-minded Mennonite college, then on to secular graduate school, then a detour to what was supposed to be a temporary stint teaching at Goshen College, and finally back home for his parents’ 50thwedding anniversary. The circuitous journey is exciting, painful, enlightening and ultimately integrative. Despite times of rejection and tearing away, many worlds come together to form a new Mennonite identity that honors the good in all he has experienced.

In recent years, Hesshas been writing poetry. In his “Three Garden Poems” he reflects on his relationship to the animal kingdom: considering how to share fruit with the robins, how to imitate the seed shucking of a cardinal, and how to make peace with a black snake. The desire for harmony—never to be fully realized—becomes more apparent in each poem.

Martha Yoder Maust, like Hess, comes from a multi-generational heritage of Mennonite forebears, but she was nurtured in a more international context. In her identity essay, “Branching Out from One Foundation,” she relates her experiences with Mennonites in Argentina and Israel, across the United States and Canada, and at three Mennonite World Conferences. Along the way she has also engaged with other Christian traditions, as well as other religions, and has found the historical “dividing wall of hostility” being replaced by bridges. Intentionally mixing her metaphors, she sees her Mennonite identity rooted in the foundation of Jesus Christ while also branching out into greater diversity and dialogue.

In her personal essay, “Gleaners,” Yoder Maustdigs into the struggle to live ecologically in a throw-away society. She values and gathers what others ignore or disdain. Gleaning thrown-out food from dumpsters becomes a metaphor for the productive way we can gather insights from a variety of sources in order to create something more enriching.

Two years ago my mother died, and the way she died reflected her free-spirited, Auntie Mame personality. In my (Ryan Ahlgrim’s) autobiographical vignette, “Mom’s Rock ‘N’ Roll Party,” I recount her final wishes and how my family carried them out. She passed on to me a commitment to creative and courageous individual expression—a quality which has not always mixed well with Mennonite identity.

My second personal essay, “Bogart and Being Mennonite,” explores how I came to terms with the tensions between the values of my parents—who had no Mennonite background—and the values of the Mennonite congregation and college that nourished my mind and spirit as I grew up. The result is a definition of being Mennonite that is truly “naked” Anabaptist.

Unlike the others in our writers’ group, Rodney Deaton had no Mennonite influences prior to joining the church as an adult. This perhaps gives him an advantage in being able to understand and embrace the soldiers—traumatized by the Iraq war—with whom he does therapy. His lack of traditional Mennonite indoctrination, as well as the influence of his maternal grandmother, also gives him a clearer view of our hypocrisies. His personal essay, “An Aggressive Mennonite,” pulls no punches as he challenges us to re-think what it means to empathize, to seek peace, to know grace, and to be Mennonite.

Rounding out our writings is a set of persona poems by Shari Wagner. Inspired by frequent visits to her uncle’s farm, and stories told by her aunt, “The Farm Wife” series of poems embodies Wagner’s curiosity regarding what life might have been like if she had lived on a farm like so many generations of her family before her. In these poems we meet a conflicted woman: anchored to the land and the solidity of her cows, yet dreaming of the ocean and sometimes taking trips without a destination. She ruminates on the meaning of snakes and tornadoes, trees and grain. She also experiences the grief of eventually leaving the farm. One of the poems, “The Farm Wife Sells Her Cows,” was featured by Garrison Keillor on his radio program,The Writer’s Almanac.

Throughout this collection of writings is a profound gratitude for a vision and set of qualities we can identify as Mennonite. But getting to these gems is not easy. They must be mined in our past and in our present. We have to get scratched up and dirty. Slag has to be cut away and left behind. And what one person finds may not be exactly the same gems someone else finds. If this writers’ group is any indication, being Mennonite has a rich and diverse future.

--Ryan Ahlgrim, Guest Editor |

by J. Daniel Hess

My Mennonite identity is like a thread made of strong …

|

by J. Daniel Hess

Robins

Since you can’t

wait any longer

I went to …

|

by Martha Yoder Maust

They say that Menno Simons’ favorite Bible verse was 1 …

|

by Martha Yoder Maust

The mural on the west wall of the old Gleaners …

|

by Ryan Ahlgrim

At the end of 1961, when I was four years …

|

by Ryan Ahlgrim

“I’m dying,” said Mom matter-of-factly, sitting on the couch in …

|

by Rodney Deaton

I am an aggressive man. And I am a Mennonite. …

|

by Shari Miller Wagner

The Farm Wife Sings

to the Snake in Her Garden …

|

|

read more from Indianapolis Writers Group: On Mennonite Identity

|

|

| + |

Working with Scripts

|

November 15, 2010

|

Vol. 2, No. 7

|

In This Issue

When I was a student at Goshen College in 1956 I sneaked downtown one dark night to see a movie, A Man Called Peter. I felt guilty even about seeing that religious film, since movie attendance was against the rules. Later during a “Nonconformity Week” series of chapel services, we were warned against seeing DeMille’s The Ten Commandments. The only theater activity on campus were plays entirely directed by students for “literary” programs, and those scripts had to be approved by a censor. Even as recently as 1978, when the Umble theater was dedicated on campus, a strong voice from the church objected, saying the college should first have got permission from the church to launch that previously questioned activity.

How things have changed! Today, Mennonite campuses have theaters and theater programs, show controversial feature films, have television studios and sponsor filmmaking programs. The official publication of Mennonite Church USA, The Mennonite, regularly offers movie reviews. The Mennonite Church sponsors Mennonite Media, which regularly offers critiques of new movies via the online Third Way Cafe and makes documentaries for use by churches and educational and commercial television channels. Dramatic segments in worship services have become commonplace. All such activity is carried out within a context of Anabaptist critique, but the media themselves—theater and film—and the acting, directing and technology that they require have found their useful place in North American Mennonite culture.

This issue of the CMW Journal highlights the work in film and theater that some Mennonite-related artists are engaged in, illustrating different kinds of work and degrees of success. If in some of the essays one also finds a self-consciousness (or even defensiveness) in being a Mennonite involved in the dramatic arts, that is to be expected, considering the distinctive Mennonite culture out of which all of them come. The four writers of scripts for commercial feature films – Don Yost, Joel Kauffman, Collin Friesen and Sidney King -- represent varied control by the writer of the final artistic work and varied relationships of their scripts to Mennonite experience and values.

A script to be turned into a film is probably the most unstable of texts, meaning the kind most liable to be altered in the process of producing the film. In classic filmography, the writer sells the script, which is then altered in major or subtle ways by the producer, director, actors, photographer, and editor. Some such process generated the feature film The Big White (2005), written by Collin Friesen, starring Robin Williams and Holly Hunter, and distributed in North America by Echo Bridge. It was filmed in Manitoba and north Canada. The Big White, which received mixed reviews, was described by one blogger as a “quirky black comedy,” which Friesen elaborates on by saying: “My stories aren’t inherently Canadian or American, they’re just inherently weird.” The script for The Big White was the first one offered to Hollywood producers by Friesen. Although he has sold several others since, he has not yet matched that original achievement. His essay, a kind of wry lament, muses on his experience in Hollywood.

At best, the normal Hollywood way of producing a movie emphasizes “collaboration.” Don Yost and Joel Kauffmann were deliberate collaborators in generating their scripts for two feature films produced for the Disney Channel, Miracle in Lane 2 (2000) and Full Court Miracle (2000). They also discuss several moments when they were involved in the actual production of the scripts. Their essay here is also a dialogic collaboration. Miracle in Lane 2 won the Humanitas Prize in 2000, and Full Court Miracle was nominated for the same prize.

Sidney King exercised more personal control over his feature film, The Pearl Diver (2005), for which he was not only screenwriter but also director. The Pearl Diver was given the Best Narrative Award at the Winnipeg International Film Festival; the Crystal Heart Award at the Heartland Film Festival; and the Grand Jury Prize at the Indianapolis International Film Festival.

The films of these four screenwriters illustrate varied influences from their Mennonite backgrounds. Although Sidney now considers writing a script for an action movie (which would fulfill an Anabaptist emphasis on doing), thus far his work has dealt with explicitly Mennonite subjects. The Pearl Diver depicts a conflict between two Mennonite sisters in Indiana and finds a way to integrate the Swiss-Alsatian tradition with the Dutch-Prussian-Russian experience. For an interpretation of this film, see Julia Kasdorf’s essay in the “Martyrs” issue of this journal (September 2009). The video Sidney produced as a college student dealt with the disappearance of Goshen College student Clayton Kratz in revolutionary Russia.

In their essay, Don Yost and Joel Kauffmann discuss how Mennonite values appear in their films, despite content that is not overtly Mennonite. However, Miracle in Lane 2 is based on the experience of an actual Mennonite family in northern Indiana, and Joel’s first film The Radicals depicts the experience of Michael Sattler, a first-generation Anabaptist martyr. It won the Silver Award at the Houston International Festival.

Although Collin Friesen elsewhere says he is a “lapsed Mennonite,” he opens his essay by saying he was willing to represent himself as a Mennonite on Craigslist, and he was happy to contribute to this issue of the Journal.

Segments from all of the films mentioned in these essays can be found on YouTube.

Vern Thiessen has written over 25 scripts for stage production, not film. Five have been published by Playwrights Canada Press. He won the Governor General’s Award for Drama in 2003 for Einstein’s Gift. Although Hildi Froese Tiessen’s long interview with him was conducted in 2000, its publication in this issue is serendipitous, since it coincides with the opening in Toronto on October 29 of his most successful play, Lenin’s Embalmers, which won critical acclaim in New York City in 2010 and is being translated for productions in Warsaw, Poland, and Tel Aviv, Israel. Like the other writers here, Thiessen discusses some of the negotiations between writer, cast and producers that occur as a script is being staged. The interview opens with the kind of warm personal exchanges between Hildi and Vern that seem to occur whenever two Mennonites meet and get acquainted.

For good measure, we publish a lively, thoughtful personal essay by Jeremy Frey, who as a stage and film actor, becomes a kind of creative pawn in the process of making a work of art. After briefly mentioning his role in Beloved (1998), he focuses on his experience of being the only Caucasian person in an all-black cast producing a play about black experience, Deep Roots by P. J. Gibson. We learn less about how a play is made, and more about what personal effect the process has on the actor. The photograph of Jeremy that accompanies his essay, from The Big Job (2010), probably represents the first time a Mennonite has introduced himself holding a pistol, ready to shoot.

Some current Mennonite screenwriters are not represented here. That is especially true of the many Mennonites who make documentary films, to which a future issue of the Journal of the Center for Mennonite Writing will be devoted.The same is true for Mennonite writers of drama, who will also be featured in a separate future issue. We welcome nominations and submissions.

-- Ervin Beck, Editor |

by Collin Friesen

It’s overcast today, which is the closest thing to “weather” …

|

by Hildi Froese Tiessen

Vern Thiessen in 2003 won the Governor General’s Award for … Vern Thiessen in 2003 won the Governor General’s Award for …

|

by Charity Gingerich

“Currently life is rich and terrifying, and I am finding …

|

by Sidney King

Screenwriters tend to spend a lot of time thinking about …

|

by Don Yost and Joel Kauffmann

Part 1 – From How It All Started to the …

|

by Jeremy Frey

Audition: You get what you risk.

One of many cattle …

|

|

read more from Working with Scripts

|

|

| + |

Christine R. Wiebe

|

October 19, 2010

|

Vol. 2, No. 6

|

In This Issue

Christine Ruth Wiebe (1954-2000) was a poet, writer, seeker, healer, nurse--a Mennonite daughter, devoted sister and friend, Catholic oblate, and Christian mystic. This issue of the Journal devoted to her poetry and to reflections about her life and work is the second part of a double issue devoted to the life and work of two unique women artists from Mennonite origins: Sylvia Gross Bubalo and Christine Wiebe. Because of size limitations, the issue was published in two parts. “The Prophetic Art of Sylvia Gross Bubalo: Enabling Constraints I” was published in September 2010 and can be found in the issue archive.

Christine Wiebe was born into a Mennonite Brethren family. Her pastor father Walter Wiebe died in 1962 when Christine was six years old. Her mother, Katie Funk Wiebe, a professor of English and Journalism at Tabor College in Hillsboro, Kansas for 24 years, became a strong feminist voice within the church and one of its most prolific writers (see her author biography in this issue). To be born into such a family with a gift for writing is not surprising, but to find one’s own voice and to carve an authentic path in writing in this context can be a daunting task.

Christine’s biography reveals a sensitive and joyful spirit intent on imprinting her vivid impressions of life in language. From a young age she created hand-made books, hand-stitched together like Emily Dickinson’s. Her writings continued to translate for friends and close family members her personal experiences of illness and recovery as she struggled to return from the threshold of death. While she longed for a life of both service to others through healing and through translating her most intense experiences in poetry, and was able to accomplish much in both areas, her lupus, and especially the medications used to treat it, made her vulnerable to heart failure and strokes which presented themselves as hard lessons and powerful subject matter for transformation into art. From these experiences she wrote and illustrated a book, How to Stay Alive, for family and friends.

This issue features a selection of Christine’s poetry, published here for the first time, excerpts and lively illustrations from How to Stay Alive, a tribute by poet Jeff Gundy, a reflection on Wiebe’s poetry by literary scholar and poet Ellen Kroeker, whose poem for Christine is also published here, a memoir by her sister Joanna Wiebe, a biographical sketch by her mother Katie Funk Wiebe, and a complete bibliography of Christine’s published work.

In Christine’s writings and life there will be much of interest to those who seek to articulate a spiritual pilgrimage in the arts, to reconcile the demands of earning a living the call to make art, and to discover a healing journey in illness and limitation. In another time and another faith, Christine might have been a Theresa of Avila. As George Eliot remarks in her Prelude to Middlemarch, there are many St. Theresas born who do not end up finding their moments of grandeur or founding an order. But fortunately for us, Christine found poetry as a vehicle to express her longings and her love of life. Her poems compel us to experience language in a new way; her journals offer insights to readers who seek to understand the artist’s vocation, and companionship for those engaged in the struggle to create.

– Ann Hostetler, Guest Editor |

by Christine Ruth Wiebe

These poems were selected from a manuscript of over 100 …

|

by Christine Ruth Wiebe

Christine Wiebe wrote this book with the hope that her …

|

by Jeff Gundy

We arrived at Hesston College in fall 1980, almost exactly …

|

by Ellen Kroeker

She turns fiercely to her right,

Curling to the lost …

|

by Ellen Kroeker

The poetry of Christine Wiebe is in piles on the …

|

by Joanna Wiebe

“As a young child,” Christine wrote about herself, “I was …

|

by Katie Funk Wiebe

Hearts starve as well as bodies;

Bread and roses! Bread …

|

by Katie Funk Wiebe

ESSAYS:

“Pacifist aim is peace,” Tabor College View. 12 …

|

|

read more from Christine R. Wiebe

|

|

| + |

Sylvia Gross Bubalo

|

September 19, 2010

|

Vol. 2, No. 5

|

In This Issue:

Art is produced when inspiration meets formal constraint. Some artists, however, must deal with more than formal constraints when they strive to give form to their work. In the case of the two Mennonite women artists who are the subject of this double issue on “Enabling Constraints”—Sylvia Gross Bubalo and Christine Wiebe—those constraints included chronic illness, gender, and the restrictions of their Mennonite contexts. Because of size limitations, the issue will be published in two parts. The first part, “The Prophetic Art of Sylvia Gross Bubalo,” is published below as the September issue of the Journal of the Center for Mennonite Writing. The second part, “Writing as Spiritual Journey: The Poetry and Art of Christine R. Wiebe,” will be published in a special October issue.

Sylvia Gross Bubalo (1927-2007) and Christine Wiebe (1954-2000) did not know each other. They were members of different generations and came from different branches of the Mennonite family—Bubalo from the Mennonites and Wiebe from the Mennonite Brethren. Bubalo was married to a kindred spirit, the artist Vladimir Bubalo; Christine remained single, though she sought out kindred spirits throughout her short life. Both women were poets and artists, although Bubalo’s formal training was in visual art and Wiebe’s in poetry. Yet the “enabling constraints” of their journeys as artists, and their understanding of art as a spiritual practice, resonate with each other.

Both women understood their art as a spiritual vocation. Both struggled with the restrictions of the Mennonite Church at a time when it was wary of embracing artistic gifts as an expression of spirituality and cautious about the leadership roles of women. Both women coped with severe physical disabilities, Sylvia with muscular dystrophy and Christine with lupus. Both were drawn to mystical expressions of faith—Sylvia through what appears to have been ecstatic religious visions, and Christine through her embrace of the Catholic faith. Both artists articulate a longing for spiritual practice lacking in their Mennonite experience, and both returned to the Mennonites at the end of their lives. Their verbal and visual art is their gift to the faith community that formed them and their artistic concerns continue to be of relevance today. By bringing their work to a wider circle of readers and viewers, we hope to enlarge its audience so that it can continue its transformative work. Look for “Enabling Constraints II: Writing as Spiritual Practice in the Life of Christine R. Wiebe” on or about October 18, 2010.

In “The Prophetic Arts of Sylvia Bubalo,” we meet the artist through her own words and images as well as through the reflections of those who knew her in life or who have responded to her work. This has been made possible by the generosity of our contributors as well as by the meticulous care with which her brother, the historian and scholar Leonard Gross, has catalogued and curated her paintings and poetry. Sylvia’s grandniece, Miriam Kirchner Gross, assisted with the selection and arrangement of the poetry. Sylvia’s “Artist Statement” serves to introduce her intention and vision to the reader. “Point of Entry,” Sylvia’s autobiography in poetry, along with related paintings and drawings, reveals connections between her artistic vocation, her faith, and the Mennonite community. Bob Regier, a visual artist and friend of Sylvia and Vladimir Bubalo, offers a reflection on the days when all three of them were students at the Art Institute of Chicago. John Blosser, a visual artist and Professor of Art at Goshen College, engages Sylvia in conversation in a rare interview. Dawn Ruth Nelson, author ofA Mennonite Woman: Exploring Spiritual Life and Identity, writes about her recent discovery of Sylvia’s visual testimony and how it spoke to her own spiritual journey as a Mennonite woman. Reproductions of Sylvia’s artwork are interspersed throughout the essays and poetry.

Sylvia’s vibrant engagement with Bible stories, reminiscent of the Jewish practice of Midrash or wrestling with the text, reveals a living faith that demanded her full resources as an artist. On the other hand, she was an outspoken critic of what she considered to be ossified practices and traditions among the Mennonites of her Pennsylvania community, especially those pertaining to women. In “Point of Entry” she recalls:

"So in baptism they said: 'Do you choose Christ and / (or) the church?' And she said: 'I choose Christ. (I can't handle the church).'"

Sylvia’s painting, “La Paloma,” portrays a stylized one-eyed woman in a flowered conservative Mennonite dress and an army helmet, sitting atop a dismantled weapon, her axe on the ground, and a dove flag, whose pole rises from the gun. One version of this painting includes the word “coraje,” which is Spanish for "rage.” According to medical anthropologist Marcia Good, women are said to have "coraje” . . . to have “nerve” . . . an expression that blends fury and courage to express an effort to surmount injustice.

Yet, as noted in a letter to scholar Reinhild Kauenhoven Janzen, it was the Christ-like spirit of many Mennonite men and women in the church, as well as the enthusiasm of her newly converted husband, the artist Vladimir Bubalo, at having discovered in the Mennonites a Church that preached the gospel of peace, that emboldened and sustained Sylvia in her efforts to conduct a ministry of art in conversation with the church. Sylvia Bubalo wrote to Janzen: “Both my grandmother and my parents and certain singular men and women taught or emanated the Christ-love. It stopped me short of rage, giving me resolve instead to become one of the voices of the same Passionate Love.” (“Art as an Act of Faith: Sylvia Gross Bubalo,”The Mennonite Quarterly Review, July 1998, 389.)

The Mennonite Historical Library at Goshen College has accepted the gift of Sylvia Bubalo’s paintings, the first major collection by an artist in its holdings, and the Archives of the Mennonite Church USA, her writings and papers.

Ann Hostetler, Guest Editor

|

by Sylvia Bubalo

|

by John Blosser

|

by Sylvia Bubalo

|

by Bob Regier

|

by Dawn Ruth Nelson

|

by Sylvia Bubalo

The major long poem, “From the Turquoise Sky 21st Century …

|

by Leonard Gross

|

|

read more from Sylvia Gross Bubalo

|

|

| + |

Serial Fiction

|

July 15, 2010

|

Vol. 2, No. 4

|

In This Issue

Some books are so wonderful that we want to read them over, or even again and again. Authors sometimes capitalize on this kind of success by writing a sequel, or two, and suddenly a series has been born. Children still love the old Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew series. Pre-teens and teenagers today relish the Harry Potter and the Twilight books and films. Many adult readers are fans of the books by Alexander McCall Smith in his No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency, 44 Scotland Street and Isabel Dalhousie series. Most recently, The Millennium Trilogy by the late Swedish author Stieg Larsson has become very popular.

This issue of the Journal of the Center for Mennonite Writing focuses on this burgeoning phenomenon by focusing on fiction that has appeared in series written by Mennonite or Amish authors, or written about Mennonite and Amish people, whether by Mennonite-related or non-Mennonite authors.

A minimal definition of “series” might be a sequence of at least three books that deal with overlapping characters in the same historical and geographic setting. The narrative may or may not be continuous, although by including characters from other books their stories are at least implied. Usually books appearing in a series can be read in any order, which militates against a narrative that continues to unfold from the first through the last books.

Among the Mennonite authors who have been given the most attention in recent years at conferences and in journals, the three novels by Armin Wiebe about Low German Manitoba culture, often referred to as his “Gutental novels”—The Salvation of Yasch Siemens, Murder in Gutental, The Second Coming of Yeeat Shpanst—is the only true series that comes to mind. Rudy Wiebe’s Sweeter than All the World is a sequel to The Blue Mountains of China and Sandra Birdsell’s The Ladies of the House is a sequel to Night Travellers. However, a sequel seems to be something less than a series. And Birdsell’s books, later published as the one-volume Agassiz Stories, really constitute a long novel of stories.

This issue of the journal foregrounds other authors who have found enthusiastic audiences and distinguished themselves by writing Mennonite-related serial fiction. They are Mennonites Judy Clemens and Karl Schroeder, non-Mennonite P. L Gaus, and the many Mennonite, Amish, Old Order Mennonite, and non-Mennonite writers who supply the U.S. and Canadian mass markets for romance and detective fiction about Mennonite and Amish people—sometimes called bonnet fiction, or buggy fiction. The most successful of these writers is Beverly Lewis. My bibliography in this issue is an initial attempt to identify these series. Notice that, although it features mainly series of “bonnet fiction,” it also includes the series by Judy Clemens, P. L. Gaus, Karl Schroeder, Armin Wiebe and the earlier writer A. E. van Vogt.

Karl Schroeder’s short story “Making Ghosts” was first published in On Spec (Hard Science Fiction Issue), Spring, 1994, considerably before his “Virga” series of four science fiction novels published by TOR Books from 2006-2009. Luddites might not be able to follow all of the sophisticated cybernetics on which the story is based, but the story deals clearly enough with how the “virtual” representation--or creation, or re-creation--of a person relates to the human desire for immortality. When we die, can we live for eternity in virtual reality? There must be something about the water of the Brandon, Manitoba, community from which Karl Schroeder comes. It is the same community that produced A. E. van Vogt, regarded as one of the best writers in the “golden age” of sci fi, and, before him, Douglas Hill and E. M. Hull.

Judy Clemens offers the first chapter of her newest book,The Grim Reaper’s Dance, second in the “Grim Reaper” series, which was released on July 1, 2010, by Poisoned Pen Press, the premier U. S. publisher of detective fiction. Poison Pen has published all five of her Stella Crown mysteries and has given Judy a contract for the books in her second series, which features the paranormal detective Casey Maldonado, whose close associate is Death. No doubt this series will draw a following, too, but her fans might well complain if she abandons Stella Crown, the tough-talking, cycle-riding Mennonite sleuth featured in her first series.

About her second series, Judy says: “During 2008 and 2009 my father was very sick from cancer. Death became a regular partner of my days as I considered what was happening to my dad. When I began writing about Casey, Death came along as a natural companion. When reviews began coming out describing Embrace the Grim Reaper as a paranormal mystery, I was surprised. Death was such a real part of my life, I hadn’t thought of it as being anything supernatural. I now see that of course it is a paranormal aspect of the book! I write Death as a genderless being so people can imagine it as they will. Most people think of it as male, but I’ve had one person who seemed surprised it would be anything but female! It’s fun to hear people’s thoughts on what Death looks like to them.”

P. L Gaus was too busy writing his seventh Ohio Amish Mystery novel, all published by Ohio University Press, to contribute new fiction for this issue, but Kyle Baldanzi Schlabach offers a critical, interpretive survey of the series. Kyle is well qualified to present Gaus, since Kyle is a native son of the same area of eastern Ohio that Gaus represents in fiction, and Kyle has also taught detective fiction at Goshen College.

As my bibliography indicates, the number of “bonnet” novels published about Amish and conservative Mennonite communities is staggering. Beth Graybill contributes a critical survey of some of the authors working in the field. The essay is a revision of the paper she presented at the "Mennonite/s Writing: Beyond Borders" conference at Bluffton College in 2006. Among other things, Beth assesses the “authenticity” of the authors’ representation of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, Amish life, which she is eminently qualified to do since she is a native of “The County” and until recently was director of the Lancaster County Mennonite Historical Society.

Michelle Thurlow focuses on the work of Beverly Lewis, who is arguably the most successful writer of Amish romance novels. In particular, Michelle gives a literary “reading” of three Lewis novels whose unity is supported by symbolic use of infants’ clothing. Michelle’s master’s degree in Christian fiction, along with her experience in teaching it, might lead us to hope that she will continue to keep up with, and publish, about this burgeoning phenomenon.

Indeed, one goal of this issue is to encourage more serious consideration of the extreme current interest, especially by non-Mennonite readers and authors, in Amish and Mennonite romance fiction. When did it begin? What historical and cultural developments have led to it and sustained it? Do the authors “get it right” in regard to Anabaptist theology, culture and experience? Why are the authors mostly non-Mennonites, or people only tangentially related to Mennonitism? What creative contributions are writers of bonnet fiction making to what readers of the CMW website regard as “Mennonite literature”?

Despite budgetary constraints, the Mennonite Historical Library at Goshen College still tries to obtain copies of every such book published, which makes it a beckoning haven for whoever will rise to the challenge of understanding this popular literature.

-- Ervin Beck |

by Beth Graybill

A few years ago, when conducting dissertation research on Amish …

|

by Judy Clemens

“This here’s my daughter Katie. She’s thirteen, and lives for …

|

by Karl Schroeder

What stands out in memory is that first picture of …

|

by Ervin Beck

Joe Springer, curator of the Mennonite Historical Library at Goshen …

|

by Jeff Gundy

We are pleased to publish for the first time a …

|

by Kyle Schlabach

Blood of the Prodigal (1999), Broken English (2000), Clouds Without …

|

by Michelle Thurlow

Although best-selling inspirational novelist Beverly Lewis is understandably …

|

|

read more from Serial Fiction

|

|

| + |

For Young Readers

|

May 15, 2010

|

Vol. 2, No. 3

|

In This Issue

At the “Mennonite/s Writing: An International Conference” held at Goshen College in 2002, Elaine Sommers Rich paid special tribute, in absentia, to Barbara Claassen Smucker for the many books she had written for young readers, most notably Henry’s Red Sea (1955). Other than that brief moment, apparently no other serious attention has been given to Mennonite writing for young readers, whether at the large Mennonite literature conferences or in published scholarly writings. This, despite the fact that the earliest successful literature written by U.S. and Canadian Mennonites was for children, stemming from books by Claassen Smucker and Elizabeth Hershberger Bauman in the mid-1950s.

The recent surge in handsomely illustrated books for children by Mennonite writers calls attention to this important area of creative writing and publication. Perhaps this issue of the Journal of the Center for Mennonite Writing will inspire more such books and the serious consideration that they deserve.

To that end, the CMW editors asked Kathy Meyer Reimer to write a preliminary critical survey of Mennonite children’s books. She decided to focus on the publications of Herald Press, the book division of the Mennonite Publishing House, since most such books have come from that press. Kathy identifies four different “eras” and at least five different kinds of books published for children by Herald Press and, in general terms, relates them to publications for children in secular presses in the U.S. Her survey and analysis need also to be applied to children’s books published by the former denominational Faith and Life Press and by Good Books of Intercourse, Pennsylvania, an independent trade publishing house founded by Mennonites, as well as those published by commercial trade houses.

For very young children, the illustrations that accompany the printed text are as important as the words in the book. We are privileged here to look over the shoulder of graphic artist Ingrid S. Hess as she describes how she proceeds to develop visuals for the books that she illustrates. Her essay is replete with colorful examples of the bold, stylized, “flat” artwork that is a trademark of her style. Ingrid, who teaches at the University of Notre Dame, also agreed to let us publish a presentation she was asked to give, regarding her work, to a meeting of Jesuits in California during the past year.

Barbara Nickel has previously won awards for her books for older children, including fictionalized accounts of classic European composers, drawing on her experience as a violinist. Like Sarah Klassen, the “featured poet” in this issue, she has also published several collections of poetry for adults. “Schnee 1939” is the first chapter of her novel-in-progress, now titled “September Cold,” which, like much Canadian Mennonite literature for adults, draws upon the historical accounts of Western Canadians, who were immigrants to the prairies from Prussia and Ukraine.

Of her plans for the novel, Barbara says: “This is a historical children’s novel that explores the relationship between two cousins who have never met, and their perspectives as German Mennonite children on either side of the Atlantic during World War II. Allegiances to country, family, and faith will be tested in complicated ways as their friendship deepens despite distance in the midst of one of the world’s greatest conflicts. The novel is based on much of my family history. My maternal grandfather emigrated to Saskatchewan in 1921 from the Danzig area, which (since WWI) was a city-state independent from Germany, although much of the population was German. He left most of his family behind, joining a farming community of Mennonites (Prussian, from the same area he’d left) who had emigrated decades earlier. My mother’s first cousin lived in Danzig, and her birthday party actually was cancelled because of the Battle of Westerplatte that opened World War II.” One incident in this opening chapter is adapted from a story told by the Canadian poet Patrick Friesen.

In the context of Kathy Meyer Reimer’s survey, it is intriguing to consider whether the work of Ingrid Hess and Barbara Nickel fits into the same paradigms of authorial intent and genres that Kathy finds in her four eras of publications. One might look for continuities, also, in the six poems published here by our “featured poet,” Sarah Klassen. Is it possible to see in her poems for sophisticated adult readers, intentions and subjects parallel to those of the writers for children discussed in this issue? In what ways do her poems demonstrate an ethical engagement with the world around her? There are no exemplary biographies in these particular poems--although one of her books of poetry focuses on the work and life of philosopher and mystic Simone Weil—but rather a deep engagement with nature, a clarity of observation, and especially in the last poem, a strong sense of social responsibility. And do we find in her poems a word and sound “magic” that might appeal, in an animated oral reading, to children too young to understand the poems’ full intentions? |

by Kathy Meyer Reimer

Mennonites claim a strong heritage of women writers--in children’s and …

|

by Ingrid Hess

To see Ingrid Hess's colorfully illustrated article about her work, …

|

by Ingrid Hess

As presented to a meeting of Jesuits at “Search for …

|

by Barbara Nickel

The sky makes him stumble out of the barn. That …

|

by Sarah Klassen

CMW is pleased to introduce readers to a group of …

|

|

read more from For Young Readers

|

|

| + |

Word Work

|

March 15, 2010

|

Vol. 2, No. 2

|

Bookbinder Image

In This Issue

Click on the link above to find the image that introduces this issue. It is “The Bookbinder,” one of 97 engravings in The Book of Trades published in 1694 in Holland by Jan Luyken (1649-1712), the prolific Mennonite engraver, assisted by his son Casper (1672-1708). The book of engravings has become Luyken’s most famous work, and the Bookbinder image has become an icon for book-binders and book conservators worldwide.

No doubt an idealized depiction, the Bookbinder seems to have reason to be satisfied, even happy, in his work. The room is spacious. The upper windows let in a lot of light and the lower windows and doors are open, letting in fresh air. In the left foreground, the worker sews signatures on a sewing frame, glue pot on the floor. In the back, the man beats the signatures prior to sewing. The round-blade “plow” at bottom right is for trimming book edges. The shelves at the left are crammed with books. Perhaps the Bookbinder is himself an avid reader.

He is doing “word work,” the theme of this issue of the Journal of the Center for Mennonite Writing. Perhaps he can represent most of the readers of this journal—poets, fiction writers, memoirists, bloggers, journalists, readers—anyone who loves words and might yearn to earn a living in some way associated with words. All of us might hope somehow, someday to attain the goal of the speaker in Robert Frost’s poem, “Two Tramps in Mudtime,” who says: “My object in living is to unite / My avocation and my vocation.”

This issue presents three Journal readers who, in very different ways, earn their living by means of words and books. Jeff Peachey is The Bookbinder’s closest descendant, since he has mastered the craft of book conservation and earns his living by it in New York City. We can tell he loves to hold and preserve the physical vessels of writing—books and pamphlets—by his clear and precise attention to the physical and historical details that the books themselves embody. Even more of his craft and insight is available through his blog that is included in the links on the homepage of the CMW website.

Marta Brunner manipulates books in a similarly meticulous way, but more theoretically, as an academic bibliographer for the graduate library at the University of California at Los Angeles. Her academic background is in English, rhetoric and the history of consciousness, not in library science, which gives hope to all that our training does not limit us to one vocation.

At the opposite pole from Peachey, who preserves books and their history, is Jane Hiebert-White, who as Executive Publisher of the journal Health Affairs, tries to keep up with the decline of words in print and the rise of words in digital form. Despite Jane’s heavy workload in Washington, DC, during the recent flurry of discussions of health care reform, she was able to rise above the chaos and craft her fine essay—like many writers, just in the nick of time.

Dr. Samuel Johnson, a lexicographer, defined his own “word work” as that of “a harmless drudge.” To some degree, the intense, minute scrutiny that our three authors’ jobs require fits that disarming description. But ask all of our writers if they enjoy their work, and you will, I am sure, receive a positive response.

One caveat: Nick Lindsay, the poet and mentor who was honored at the Mennonite/s Writing Conference in 2006 at Bluffton College, always urged his creative writing students NOT to try to earn their living by writing literature or teaching creative writing, lest the job ruin the art. Nick eventually left his teaching position at Goshen College and returned to Edisto Island, South Carolina, where he built winding stairs and fiberglass boats. Perhaps, in light of his warning, the three essayists in this issue have found the golden mean of “word work” between the extremes of “mere work” and “literature.”

This issue concludes with a series of linked poems by David C. Wright. He is the “Featured Poet” for this February 2010 issue, to be followed by Sara Klassen in May and Jeff Gundy in July. Wright’s five “Sarabandes” represent a new direction in his published poems. Instead of the sharp, chatty, witty and always insightful poems that we have enjoyed earlier, here he experiments with pure lyricism and emotion, responding to performances of cello music by Bach. The poems are examples of ekphrastics, or the interplay between one artistic media and another, in this case music and poetry.

The Bookbinder engraving that introduces this issue is also ekphrastic art, since it integrates image with poetry, creating a kind of Renaissance emblem. The Luyken text has been newly translated by Jan Gleysteen and Leonard Gross:

The Eye of the Eternal Being,

Can read the book of your heart.

If knowledge were hidden in secret corners,

Showing us the way to heaven,

It would be worth searching the world for it;

But now it has been clearly told to humankind,

In the Holy, God-given Book. Respond to it by holy living!

Ervin Beck, Editor

|

by David Wright

|

by David Wright

"A real diehard, indestructible, irresolvable obsession in a poet is …

|

by Jeffrey S. Peachey

A book conservator often enters into public perception heavily colored …

|

by Jane Hiebert-White

Sometimes change creeps up on you, slowly, without clear signposts …

|

by Marta Brunner

I didn't set out to be an academic librarian. In …

|

|

read more from Word Work

|

|

| + |

New Fiction

|

January 15, 2010

|

Vol. 2, No. 1

|

The title of this issue is a bit misleading, since some of the authors included have published fiction elsewhere, and the piece by Keith Miller is excerpted from his second published novel. But the title does capture the intent of this issue, which is also one of the goals of the CMW website as a whole: to offer unpublished authors a friendly venue for publication; to bring to the attention of CMW readers Mennonite writers early on in their publishing careers; and to make accessible the writings of Mennonites who might be unfamiliar to many readers of this journal. The seven very different fiction-writers in this issue fulfill these intentions in a fine way.

The issue also is intended to encourage the writing of fiction in the Mennonite community. Periodicals tend to favor poetry, which takes up less space. Readers can easily embrace a lyric poem, and move on if they don’t like it. Fiction requires more space from the publisher and more patience and commitment from the reader.

To pose a provocative, winless debate: it may also be easier for most people to write a good poem than to write engrossing fiction. If William Wordsworth is right, a poem springs from a “spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling,” which everybody experiences from time to time. Any person literarily inclined might be able to write at least one good poem in a lifetime, based on such experience.

A short story might also derive from personal experience—hence the close association between memoir and fiction—but perhaps it requires a fuller, more complex set of competencies and inspirations to create “believable” setting, characters, narrative, conflict, dialogue, resolution and idea (to invoke the classical ingredients of fiction).

As has often been noticed, Mennonite writers in Canada have tended to excel in fiction, as in the remarkable work of Rudy Wiebe, Sandra Birdsell, David Bergen and many others. Mennonite creative writers in the U.S. have produced much fine poetry, but much less fiction. That situation is remedied here a bit by a preponderance of U.S. authors: Keith Miller, Ryan Ahlgrim, Tim Stair, John Liechty and Linda Wendling

The seven pieces of fiction published in this issue prove once again that Mennonite literature is no predictable, monolithic body of work. The pieces are so varied that it was hard to arrange them in a fruitful sequence, and it is even harder to generalize about their connections.

The sequence begins with fiction by Keith Miller and Ryan Ahlgrim, both of whom move us beyond mundane reality into kinds and degrees of fantasy. Miller clearly writes in the tradition of Borges and other magical realist writers by creating a new world that bears little correspondence to daily life. Ahlgrim begins with mundane reality in Indianapolis, which gradually modulates into the realm of fable and poses a moral view of life, even if that “moral” is hard to pin down. Miller’s “Library of Alexandria” avoids any moral and lifts the reader into the purely imaginary, aesthetic realm. Miller’s piece welcomes the reader into the world of imagination in which the writers who follow him also dwell.

The next three pieces, by Dora Dueck, Tim Stair and Linda Wendling, exploit the idiosyncratic views of first-person narrators. Dueck’s short story seems so close to life that the Journal editor initially mistook it for memoir, although the complex narrative strategies in it signal that it is art more so than life. Stair’s narrator is so witty and saucy—and so different from its pastor author--that we relax, enjoy the humor and look forward to the unwinding of a picaresque tale. The most extreme, idiosyncratic, surprising – and biographically and emotionally complex -- narrator is Wendling’s God-haunted Hope, whose story becomes the most overtly religious one in the set.

The sequence concludes with two third-person narrations. Janice Dick offers the beginning of an unfinished historical novel, set in Siberia, that promises to add one more variant to the archetypal Russian Mennonite narrative of migration because of persecution. John Liechty creates a central figure who is an alien by choice, teaching English in an Arab country, almost despite himself. Dick’s chapter sets up a romantic, melodramatic story line, whereas Liechty’s selection comes from a picaresque novel that is funny, ironic and richly allusive to experiences found in Mennonite history and western literary classics.

A welcome response to any or all of these fictions would be comments addressed to authors on the CMW website blog. Any response is an encouragement. Feeling ignored is the worst fate a published writer can experience.

Ervin Beck, Editor |

by Dora Dueck

The year I was eleven and Danny was ten, our …

|

by Ryan Ahlgrim

The special invitation came in the mail. Inside an oversized …

|

by Linda Wendling

…if your killer is the nicest person you know, it …

|

by Keith Miller

Excerpt: The Library of Alexandria

In tremendous caverns, bookshelves lifted …

|

by Tim Stair

Chapter 1

Be careful at family reunions. I wouldn’t have …

|

by Janice L. Dick

Chapter 1

Alexandrovka, Slavgorod Colony, Western Siberia — 1926

The …

|

by John Liechty

Chapter 7: In This World

Fretz – “Mister John” to …

|

|

read more from New Fiction

|

|

| + |

"New" Mennonite Voices in Poetry

|

November 15, 2009

|

Vol. 1, No. 6

|

A Celebration of “New” Voices in Mennonite Poetry

In a recent talk broadcast on TED, the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warns against “the danger of a single story.” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg

Although her focus is on African writers, and the ways in which western readers are apt to read a single work of fiction by an African writer as representative of all Africans, Adichie’s insights can productively be applied to a discussion of Mennonite literature. According to Adichie’s logic, cultures with great economic power have the privilege of telling many stories about themselves, but cultural minorities too often only have permission to tell “one” story to outsiders. If the story a minority writer tells deviates too much from the “script” of the single story, then the story is deemed “inauthentic” by critics outside the minority group, who have known the group primarily through this “single story.” Too often, their criticisms gain support from insiders who disagree with a representation of their culture that does not match their own experience. Yet, as Adichie convincingly argues, we are all people who have multiple, overlapping stories to tell.

Reading poetry, I’m convinced, is a way to expand one’s capacity for entertaining a variety of stories . . . as well as their containers made of language. Lyric or non-narrative poetry may not offer story as such, but it allows us to look at the world from different vantage points, illuminated through the lenses of other minds. While readers may lack time or patience to sample multiple works of fiction, they may be enticed to read a variety of poems. Poems, after all, are short. We’ll reserve the “New Fiction” for the January 2010 issue of the Journal, after we have offered readers a taste of poetry.

While I was editing A Cappella: Mennonite Voices in Poetry (University of Iowa Press, 2003), I was delighted to discover a whole range of diverse voices, each offering a unique perspective from the roots of a heritage whose churches have split over and over again because they insist on a single version of what is in fact a capacious and multi-faceted story. Mennonites have for so long been misunderstood by outsiders, a state of affairs complicated by the tremendous range and variety that exists among Mennonite groups. Individual Mennonites also tend to become extremely uncomfortable with representations of their cultural and religious group that do not reflect their “own” experience or understanding of Mennonites.