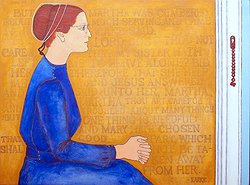

She sits quietly, hands folded, looking at a door with the lock hanging open. I found her at an art exhibition in a Mennonite historical museum in the fall of 2009. Who is she? What needs unlocked? Who painted this picture? I was stunned and full of questions. This could be me although she’s a woman in a plain dress, a cape dress, a block of brilliant blue color like the Amish wear, with a covering over her long hair in a bun. I never dressed like that. But I am a Mennonite woman and something in me is touched by this unlocked door.

Is it like the image of the open jar in Sue Monk Kidd’s novel The Secret Life of Bees, a story of a girl who finds sanctuary in the home of three bee-keeping women? In this book there is a powerful image of freedom. The bees have been let go, but they’re still swarming around the inside of the jar, not realizing the lid’s off.

Is that what’s happening with this woman? Or is it like the central image in contemporary Catholic writer Joyce Rupp’s book, The Open Door, where Joyce asks: what doors are standing open in your life and what would happen if you went through them? This is the beauty of pictures or images – they could mean all of the above and more. They speak in layers; they unfold for you. They unfold you.

A further clue tells us more about the picture – the very faint words scattered all over the background, some standing out more quickly than others: “Mary has chosen;” “one thing is needful;” “[b]ut Martha was cumbered;” “much serving.” I recognized the biblical story of Mary and Martha. At first glance I didn’t know if these were just random words from this story. Someone suggested I look at the King James Version and that was when I saw that the artist had the whole story from the King James version in the picture - no words were skipped! The words were all fitted around the central image of the woman. In the language of the Bible translation the artist grew up with - I found out she was Sylvia Gross Bubalo - here is the whole story: “But Martha was cumbered about much serving, and came to [Jesus] and said, Lord dost Thou not care that my sister hath left me to serve alone? Bid her therefore that she help me. And Jesus answered and said unto her, Martha, Martha, thou art careful and troubled about many things; But one thing is needful and Mary hath chosen that good part, which shall not be taken away from her.”

“One thing is needful” is emphasized by the artist so that it jumps out at the viewer, as do the words “Mary” and “ chosen.” I’m drawn in, because this is a story that has meant much to me over the years, and that I’ve used for preaching, to describe what contemplation feels like - the focus on one thing. More than that, it is a story that I think applies especially well to people who grow up with a service and community emphasis in their Christian faith. The picture is called “Martha”, and that title would work just as well for the whole Mennonite community. We specialize in service. This story speaks to us because it does uphold the importance of service – Jesus enjoyed Martha’s hospitality or he wouldn’t have come back to her house so often for refreshment. But the story is really about the importance of something else: the importance of paying attention, of stillness, of listening, of simply “being with”. The story explains much of my own journey toward more focused prayer and worship. There is more than service in the Kingdom of God – there is a Person at the center who asks for our attention - a Person we can sit with, be with, who sets us free when we do that. And not just people in general but women in particular - in this story - free to pay attention to the one thing necessary. This call comes even to women, whose lives are so often cluttered with attention to everyone and everything else.

Katie Funk Wiebe in her memoir You Never Gave Me a Name says that women resist being drawn away from their Martha tasks because it is challenging to really meet Someone in this way. Wiebe quotes “writer Gail Ransome [who] argues that she saw women preferring to stay in the kitchen like Martha rather ‘than face each other as merely human, fully present, ready to be touched, changed, moved by the presence of another, by the presence of the incarnate God’” (Wiebe 190). You could say the same for all of us, men and women. We’d all rather not be touched, changed and moved. But there’s that pull of the open door.

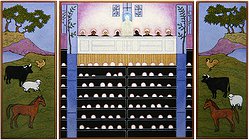

This was just one of Sylvia’s pictures. Browsing further around the art exhibit, I was stunned, pierced, encountered by the spirit of a person, an artist, who turned out to be from my local community but who was born some years earlier. And, as it turned out, she was already gone; she died in 2007. Who was this artist, where was this woman all my life? This Mennonite female Chagall I never knew existed till she died? Was she too dangerous? I needed to know more of her story as I wandered amid floating ecstatic men in plain coats, images of rows of congregants in pews with a smiling sun just outside the walls, flying covering strings, women peace warriors in army helmets and cape dresses. I felt I’d found a kindred spirit I’d never met.

There was an article from a scholarly journal, The Mennonite Quarterly Review of July 1998, sitting beside the pictures at the exhibit. I devoured the article called “Art as an Act of Faith: Sylvia Gross Bubalo.” It included interviews with the artist and interpretations of the pictures. I wanted to know more about who she was. It turns out that Sylvia Gross Bubalo not only grew up nearby but she went to the same seminary I did many years before. I learned a little chronology of her life. The author of the article, Reinhild Kauenhoven Janzen, an art history professor from Washburn University, in Topeka, Kansas, had discussed with Sylvia about 80 of her works and had corresponded with her. A striking quote from one of Sylvia’s letters began the article. “Both my grandmother and my parents and certain singular men and women taught or emanated the Christ-love. It stopped me short of rage, giving me resolve instead to become one of the voices of the same Passionate Love.”

This is what I had seen in the pictures! A Passionate Love. The word “emanating” is a very visual way of talking about love. It makes sense that Sylvia as an artist saw love in a visual way. I saw her image of a powerful light, a sun, in many of her pictures, and resonated with this symbol for the spiritual power at the core of the universe. I responded because I have also experienced this power that comes in images of tremendous heat and power like the sun, with a desire so strong it can melt and mold us but unlike the sun, does not consume us.

Her brother Leonard says: “At the center of Sylvia’s creative efforts lies a strong spiritual motif…. Through her art, Sylvia interpreted life honestly and with strong vision and idealism. She wrote, ‘My aim is for my work to be a window or door to the spiritual, and not an end [in] itself.’ Her artwork and poetry betray her deep interest in things spiritual, drinking deeply as she had always done from stories of the Gospels.” (www.goshen.edu/pressarchive/10-22-08-bubalo-exhibit165.html)

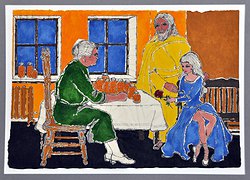

She drank deeply from the Mary-Martha story. There is more than one picture of it. It’s the other picture that really grabbed me. In this picture Jesus’ affirmation of Mary is highlighted even more. There are three figures instead of just one. Jesus is actually present along with both of the women this time. In fact, he stands behind Mary with his hand on Mary’s shoulder. His position in the picture says to me, “I’m over here with Mary on this one.”

Martha is in a cape dress, sensible shoes and covering again – I love making biblical stories right up-to-date, which this would have been for Sylvia, very much about her own real life in the mid-20th century – though this woman is older than the previous “Martha.” This time Martha has a row of canned goods in front of her of which she is very proud, you can tell. But she is not belittled in the painting. She looks content and the canned goods are beautiful in their own way. It is the anomaly of Mary that is most striking, though. Mary looks like Sylvia perhaps, with long curly hair, dancing shoes or ballet slippers (not sensible shoes), a dress that’s open to her thighs, no canned goods to show for herself but a rose in her hand.

Reinhild Janzen says that in another of Sylvia’s paintings she herself said that a flower “stands for the Beautiful and the Non-functional (the capitalizations are Sylvia’s)…” (392). In this picture “Mary” offers a rose instead of “functional” canned goods. Everybody knows what to do with canned goods. What do you do with a Rose? I once spent time on a silent retreat admiring a crabapple tree in bloom. Its deep pink flowers were arrestingly beautiful, and I had lots of time to drink in their beauty. But the color was “useless” (my word for “nonfunctional”) in terms of the values of my religious tradition. You might even say “frivolous.” Beauty was its only “purpose.” This meditation-on-fuschia-crabapple freed me to also pursue more of the “Beautiful and Non-functional.” Something in me needed this tree, to help me ignore some of the values of my past while pursuing others.

A friend was talking about his relationship with a Mennonite step-father 30 years ago. I was struck that he said: “Obedience was more important than relationship.” This approach to parenting comes straight out of the recent Mennonite tradition in which the Martha service-obedience is more important than the Mary relationship-stance.

I still wonder: Is there some reason why I never knew of this woman – who grew up around the corner – till she was safely dead? Is there some form of dynamite here? Her picture of a row of men in plain suits standing stiffly – titled “Mennonite disciples” – tells of a comfort in sameness but a blandness as well.

Her pictures for me reveal a sharp critique as well as a love of the tradition. Interesting that Reinhild Janzen actually articulates the critique I “read” in her pictures, using these words from Sylvia in a letter to the author. Sylvia says: “…the Catholic and Episcopal churches make room for both vita contemplativa and vita activa, ours did not. Anabaptists evicted the mystics from the start and to me that has been part of what is missing from our church ever since. The so-called practical has been so elevated, almost deified, thus excluding gifts of creative ones, including the physically limited” (MQR, July 1998, 408).

Reinhild Janzen closes her article on “Art as an Act of Faith” with a quote from theologian Gordon Kaufman, who “has called upon theologians to explore seriously ‘theological insight that may be manifest in works of art’ because such works are not necessarily merely illustrations of established theological truths but may offer new understanding not arrived at by the traditional methods of teaching and learning theology” (410.) I find new insight and new understandings about myself and the tradition I love in Sylvia’s work and in her life as a creative, physically limited woman.

August 2010