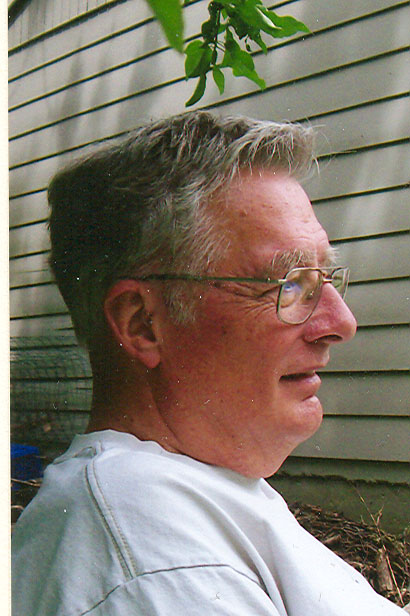

Doug Reed, part time playwright and full time computer programmer, has mobilized members of his Madison Mennonite Church congregation for the production of his latest drama, The Lamentable Tragedie of Scott Walker, Govnour of Wisconsin. The official drama program credits thirteen members from the Madison Mennonite Church for their contributions as part of the Broom Street Theater’s “Most Capable Crew.” Eight more from the congregation are thanked in the credit line.

Reed wears his Mennonitism lightly. His personal story as an artist is not the typical ethnic narrative of struggle for freedom against repressive puritanical traditionalism. He grew up not in a rural or small town Mennonite heartland, but in urban/suburban Richmond, Virginia. He studied playwriting under Lauren Friesen at Goshen College. He claims he still has a key to the Umble Center (if they haven’t changed the locks since 1990) where he developed his dramatic skills in Shakespearean and other plays.

Reed’s most recent play is political satire in Shakespearean mode. The target of scorn is the administration of Scott Walker, elected Republican governor of Wisconsin in 2010. The new governor blitzed the state with a conservative program allegedly to balance the budget by weakening public service unions, cutting corporate taxes, and reducing a host of benefits to the poor and disadvantaged. Walker’s program resulted in a storm of popular protest. Doug Reed, whose “politics are proudly liberal,” joined the thousands of protesters at the Capitol. He posted on Facebook a passionate “Open Letter to My Conservative Family & Friends.” Parts of Walker’s “budget repair bill” he said, were “either gobsmackingly corrupt or screen-door-on-a-submarine stupid. Probably both.” The post was widely forwarded.

In February of this year Broom Street Theater assigned to Reed the summer slot for a new drama. Broom Street (“which abideth not on Broom Street”) is a small experimental theater with seats for some sixty spectators a mile or so east of downtown Madison. It is not accustomed to runaway popular drama productions attended by state senators and noted by national media figures. (On August 4 Rachel Maddow’s blog commented on the drama.)

Early in the writing process Reed recruited Carola Breckbill, a costume designer and fellow member at Madison Mennonite. Would she be interested in creating Elizabethan-era costumes for a Walker-bashing drama? Breckbill was already upset with the Walker administration’s male posturing. “How big do you want the codpieces?” she asked.

Reed approached another Madison Mennonite family for permission to use their personal story. Walker’s reforms threatened this family with a triple whammy. They had a disabled child whose public assistance funding stood at risk; they would be affected by cuts to public education; and their paychecks as public service employees would take a substantial hit. Their story reminded Reed of Charles Dickens’ Cratchit family from A Christmas Carol.

But how could Dickens’ lovable Tiny Tim and his virtuous parents be brought into a comic/tragic drama built on a Shakespearean frame? Reed says this was the first time in his playwriting career that he portrayed real-life characters who he wasn’t “trying to piss off!” He turned Bob Cratchit into Governor Walker’s fool, who is fired from his job in the second act because a fool must tell the truth. Mrs. Cratchit, for her part, stands on a domestic soap box to deliver a speech calling for affordable health care for all. Her real life counterpart from the Madison Mennonite congregation in fact had stood on a box with a megaphone in the Capitol to point out the harmful potential of Walker’s reform for Medicaid recipients.

How can a spare-time playwright create successful dramas in the margins of vocational and family responsibilities? Reed says he has turned himself into a “morning person.” He does his writing in early mornings between five and seven o’clock. He puts his ideas and tentative dialogues onto dozens of pieces of paper scattered in bunches and tacked onto a large office bulletin board. No one but the playwright could make sense of the chaotic layers of notes. Reed’s dramas take shape out of incoherent insight, rather than out of a clear preconceived outline.

Reed says it was a struggle at first to write in the iambic pentameter required of his Shakespearean Governor Walker. After a time, however, with the rhythms coursing through his mind day and night, the text began to flow more easily. Outrageous events in Wisconsin’s unfolding political scene gave the playwright plenty of material to lampoon. Fourteen Democratic state senators fled to Illinois to deny the Republicans the quorum needed to pass the budget bill. A prank caller pretending to be conservative billionaire David Koch got the respectful ear of a duped Governor Walker. Police guards botched attempts to lock protesters out of the capitol building.

There are precedents for faux-Shakespearean lampoons. In 1967 playwright Barbara Garson skewered President Lyndon Johnson with the story line of a single Shakespearean drama, Macbeth. Reed’s Lamentable Tragedie is more eclectic. Reed was influenced by the work of the popular “Reduced Shakespeare Company” that purports to condense all of Shakespeare into a single production. Reed quotes well-known lines and scenes from many different Shakespeare plays. There is a balcony scene (Romeo and Juliet), an “Out damned spot!” confrontation with guilt (Macbeth), a contemplation of a skull (Hamlet), and many more. Sword fights abound.

Actually, Reed’s Walker refuses to engage the skull and its reminder of mortality. This ruler rather resists the dignity of tragedy. Perhaps the most creative literary turn of Lamentable Tragedie comes when the drama reaches the point requiring a profound soliloquy from the would-be hero. Alas, Governor Walker can’t soliloquize. He vacantly rejects repeated invitations to say something significant. Instead he flips on the TV to watch some flickering drivel on the tube.

The Lamentable Tragedie, pointedly lacking a tragic hero, ends with a hopeful call for popular democracy. The hapless governor meets his end in a struggle with “Lady Wisconsin,” the golden symbol of democracy who stands atop the state Capitol. The audience joins the protesters in a rousing chant: “Tell me what Democracy looks like; This is what Democracy looks like!!”

Will “Democracy” win in Wisconsin? While The Lamentable Tragedie was in production the anti-Walker forces succeeded in removing two Republican state senators in recall elections. But they failed to achieve the goal of a Democratic majority in the state senate. The Republicans remain in control of all three branches of the government. Plans are under way for a recall election to remove Walker in 2012. That will be an uphill battle.

Doug Reed’s drama, however, has been a roaring success. It played to sold-out audiences during its six-week run at the Broom Street Theater, July 29 to September 4. Local drama critics praised the play. Some Democratic state senators portrayed in the drama, not with unqualified approval, attended the play and warmly congratulated the playwright and the cast. The Bartell Theater is offering a second sold-out run of the production from November 11-19. Several theaters have contacted Reed about writing additional plays. Reed seems quite surprised by all the acclaim: “I fear I have reached heights with this play that I’ll never reach again.”

Although Reed has always gotten support for his dramatic endeavors within the Madison Mennonite congregation, the level of support for The Lamentable Tragedie will be hard to top. And his non-Mennonite friends see him with new eyes. When Reed recently outed himself as a Mennonite on his Facebook page one of his “friends” wrote, “You, a Mennonite?! It all makes sense now.”