At the height of the Roaring Twenties, on November 25, 1928, Sylvia Gross (Bubalo) came into this world, in Doylestown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Born into the Mennonite world of that day, a world set apart from that of the flapper generation, or even that of the more demure Thirties, Sylvia was destined to become a Mennonite, growing up in a traditional (old) Mennonite setting.

But not exactly. For Sylvia started out life with a physical condition only decades later diagnosed as muscular dystrophy. Disabilities sometimes sharpen up other areas of human activity, and for Sylvia, a highly developed intellect became her mainstay of life, which she used judiciously, and effectively.

Sylvia was also an unabashed feminist. For example, when the bishop of the church came to her, one day, telling her to stop curling her hair, since such was a sin and against the rules and discipline of the church, her reply was: “It is naturally wavy, any suggestions on how I might straighten it out?” – leaving the astounded bishop nonplussed.

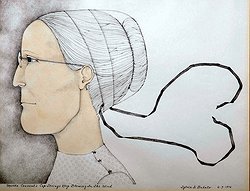

Sylvia contended with many a minister, confounding them with her astute knowledge of the Bible. Two of her paintings, among others, illustrate this aspect: The Last of the Red-Hot Papas and Martha Convent’s Covering Strings Keep Blowing in the Wind.

Born to be an artist, Sylvia enjoyed drawing and painting for as long as she could remember. At Doylestown High School, art teacher Melba Lukens mentored Sylvia, returning her work with carefully written commentary and critique. At Goshen College, she took all art classes offered at that time (1947-51) under artist Art Sprunger, completing an art minor.

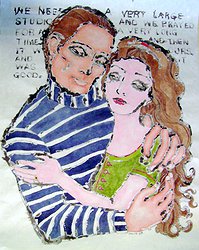

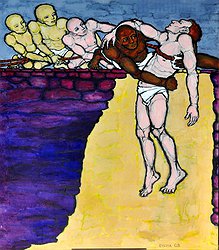

Sylvia came into her own at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she studied from 1955 to ‘59, and where she also met Vladimir Bubalo, her “Abe Lincoln,” a Chicago artist whom she married in 1957. Sylvia’s thick portfolio of work at the Art Institute illustrates her creative use of diverse media in two-dimensional works of art. Beginning in the mid-1950s, she produced profound works in oil or acrylic on canvas, watercolor or gouache and Sumi ink on rice paper, and numerous smaller works in watercolor, ink, and graphite. As her muscular dystrophy progressed, her husband assisted her, enabling her to continue working.

Upon the death of her husband in 1989, Sylvia abruptly stopped painting and turned exclusively to the world of poetry. Her more than 250 poems encompassing close to 600 pages were written from the 1950s to 2007, shortly before her death.

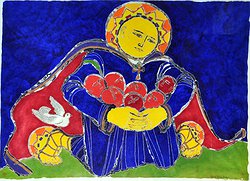

Her poetry and art productions betray her intense interest in things spiritual, drinking deeply as she had always done from the stories of the gospels. Central in her faith and life was the reality of the spiritual Christ, founded on the very human Jesus of history whom we are to follow.

At the center of Sylvia’s creative efforts lies a strong spiritual motif. This may have been inspired in part by her years of study at the Mennonite Biblical Seminary in Chicago (1953-55), as well as by her Mennonite upbringing – although she considered herself “not a Mennonite artist, but an artist born into a Mennonite tradition.” Through her art and poetry, Sylvia interpreted life honestly and with strong vision and idealism. She wrote, “My aim is for my work to be a window or door to the spiritual, and not an end [in] itself.”

Sylvia became a genuine urbanite, eager to expand her broad literary interests, a path that she pursued throughout her years. She lived in Chicago (1953-70) and Seattle (1976-86), but also in Scottdale, Pennsylvania.(1970-76) and Goshen, Indiana (1947-51, 1986-2007). Over the decades, and up to the very last day of her life, those who visited Sylvia soon found out they were entering Sylvia’s world. And an amazing world it usually turned out to be, spiritual, political, literary, each in its turn.

But Sylvia could also listen, and remembered many details of the other person’s life and experience. Sylvia then created, out of this complex assortment of personalities, something that remained with her all her life: candle time, a time of thoughts and prayers for a whole cadre of individuals, ongoing – candle time, late into the night and into the early morn.

On October 30, 2007, Sylvia passed from this world, into the cosmos of the Eternal.

– Leonard Gross (September, 2010)