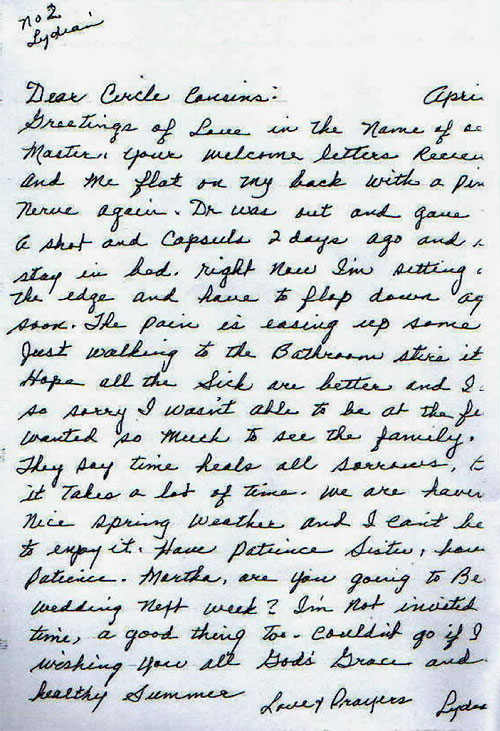

The Old Order Amish and Conservative Mennonite women of the Oak Glen community follow communally constructed rules when they write letters. While these ways are not regulated officially—that is, although the church oversees and regulates communal practices, no one in authority censors these letters—they are, with little exception, regulated by the women of Oak Glen. The letters, often rather brief, contain a salutation consisting of greetings in Jesus' name or some reference to God, an update on personal health issues, a reference to the weather, and sometimes a chronological cataloging, or diary-style listing, of daily activities (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Letter by Lydian Hochstetler.

Communal rules for letter writing are constructed within the context of relational dynamics. Mothers and daughters, sisters, grandmothers and grandchildren, cousins, aunts and nieces, and friends, regardless of age, all exchange letters. While some of these women now have telephones, few use them to keep social ties intact. The letter persists from a time when telephones were banned by the church and the difficulty of arranging transportation prohibited many personal visits. While next door neighbors do not exchange letters, relatives and friends living five miles apart do so in the Amish community. Five miles by horse and buggy is too far apart to be in the same church district, which means that the women may not see each other often.

When the Oak Glen women send birthday and Christmas cards, they include a letter, handwritten on ruled or un-ruled six-inch by nine-inch notebook paper. A woman is not performing her social duties if she fails to include a letter. One woman, housebound by her inability to drive a car, is disgusted if she receives a card with no letter. "There's no point in spending the money for the stamp if there's no letter inside," she often states. Women labor many weeks before Christmas to write a personal letter to each person on the Christmas card list and include the letter inside the card.

Oak Glen women take pride in the fact that they do not let a letter "sit long" before they have answered it and sent it on its way. Ultimately, neglecting a letter is neglecting a friendship, and a woman risks severing familial and friendship ties that have been carefully nurtured by the letter. The neglectful woman who persists in this pattern soon finds herself receiving few to no letters. Women who do not answer quickly are excused if there are extenuating circumstances. For example, illness in the family and an abundance of garden work are legitimate reasons for neglecting a letter.

These women, not surprisingly, have found a way to conserve the time and energy spent on this time-consuming ritual. They use a "circle letter." Circle refers to the group of women to whom the packet of letters is circulated, and circle letter is the packet of letters as circulated in the designated order. That is, the letter begins with one woman who is a member of a group of women who want to be in a circle, and the letter makes a full circle back to the first woman after it has been sent to each member.

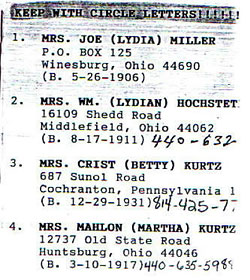

The woman who is known in the circle as No. 1 begins by writing her letter and including in the envelope a list of the other pre-chosen women, their addresses, and often their birth dates. The names of the women are numbered in order as they appear on the list.

The number beside a woman's name functions as a code (Fig. 2), providing an efficient way for other members of the circle letter to refer to her. This list may be handwritten, but more often it is typed. It is cut to the size of a business envelope as an insert that is permanent and endures many mailings. The list functions not only to supply the names and addresses of the circle letter members, but also to dictate the order in which the letters are sent. This same order is required for each circle the letter makes.

Fig. 2. Partial list of circle letter members inserted in circle letter packet.

The first woman sends her letter and the list to the second woman on the list who, in turn, adds her letter and mails it on to the third person on the list, and so on. The last person on the list sends the packet to the first person on the list. When the letters return full-circle back to the first woman, she removes her original letter, adds a new one, and mails the packet to the second woman once again. The list of women's names and addresses is the only piece of paper that remains constant in the envelope as the letters are mailed in the circle.

In my larger project, I examine three circle letters to illustrate, respectively, how a circle letter begins, how one endures, and how one can finally come to an end. Here, I focus upon the one that finally came to an end.

Oak Glen Circle Letter

This circle letter had eleven members who are related to one another in some fashion. The elderly woman, Lydia, who began the circle letter, lived in Ohio, had no telephone, and wanted regular contact with her cousin, sisters-in-law, nieces and two wives of nephews. She wanted the circle letter kept small so that the letters would arrive swiftly. She was housebound and depended upon personal visits and letters for her communication with the outside world. Consequently, she chose the members with care, those to whom she felt especially close and those who admired and loved her. She included a first cousin who lives 150 miles away; three sisters-in law who live in Pennsylvania, Ohio and Florida; a daughter who lives in Indiana; three nieces who live in Ohio and Delaware; and the spouses of two nephews living in Ohio and Florida.

The list structuring the circle letter is typed, with these instructions in all capitals running across the top: "KEEP WITH CIRCLE LETTERS!!!!!!" The members are numbered 1 through 11 and are identified by their married status, their husbands' names, the women's first names in parentheses, followed by their last names. This line is in all capitals: "MRS. JOE (LYDIA) MILLER." The address follows in two additional lines. Under the last address line is a fourth line in parentheses giving a member's birth date: "(B. 5-26-1906)." Since the woman who began this circle letter was Old Order Amish, she did not include a telephone number. However, at some later date, members began penciling in their telephone numbers, including this woman's daughter, also Old Order Amish, who wrote in her neighbor's telephone number.

This circle letter existed nearly eighteen years before it ceased altogether. However, during that time, circulation slowed and even stopped altogether a few times, even though one cousin regularly ended her letter with "Hurry back!" As they discussed these problems, some circle letter group members pointed their finger at one of the nephews' wives. She took a month or more to answer the letter, and sometimes she forgot about it altogether. Her procrastinating ways caused discord. Lydia's daughter eventually refused to be in the circle, stating that it took too long to "come around." She would not rejoin until the other woman was excluded. Her mother finally agreed to exclude the neglectful nephew's wife, and efforts were put forth to rescue the circle letter—a rescue that depended on the exclusion of the errant member.

This action caused some confusion. Lydia's Old Order Amish niece writes on December 14, 1993: "I received these letters today. Was so good to hear from everyone. I did talk to Lydia [another circle letter member] in town & she said they're changing the circle letter. I'm not sure who to send it to. There's no address sheet with the letters. So will send it to Aunt Lydia." However, the excluded woman's mother, also in the circle and thinking her daughter's name had been forgotten, included her again. She writes in her section of the circle letter on January 30, 1994: "Was surprised and glad to see that someone started the circle letter again. Was it you, Lydia? I'm going to put the list in that we had before. If any one doesn't want to be in the circle letter just cross out your name and send it on to the next one. You can also add others if you wish. I took out the other list so it wouldn't be confusing. I'll keep it in case we need it again. Hope this is O.K."

No one crossed out the nephew's wife's name, and no one added names. For another four years the letter took its time going around the circle. Eventually, the nephew's wife forgot to write one time too many and broke the circle for good. Gradually, the circle letter members realized the circle was broken, but by this time they did not have the will to keep the circle going. No one made an additional effort. By the time another year passed, three members were deceased, including the woman who had begun the circle, her cousin and one of her nieces.

The Letter Writing Practice Ritualized in the Circle Letter

Under normal circumstances the letter-writing practices, as ritualized in the circle letter, endure in the unbroken circle, keep the relational ties strong, and assure the circle letter members of communal continuity. While writing is valued by both Oak Glen men and women, different kinds of writing are relegated to male and female roles in this community. These gendered tasks are particularly visible in the literacy practices of the Oak Glen Old Order Amish community. Women write the letters and cards to sustain communal relationships as dictated by the church.

For example, during the week between Sunday church services (formal services are held biweekly), each Old Order Amish Oak Glen home receives a copy of Der Gemeinde Brief [The Church Letter] published by Mespo Printing. This publication usually consists of six standard-sized sheets of paper stapled together, and it brings the news of the church to the Old Order Amish Oak Glen families. Among the "news" items are directives from the bishop and ministers to send letters and cards to fellow church members:

Mary S. Miller was unable to attend church the last 2 times. She appreciates cards and visitors; Mrs. Crist T. Kuhns has cancer so please, known and unknown friends, won't you please send her a few lines? Mail is such a nice pastime and something to look forward to. Thank you; Joe Troyer has been laid up for awhile because of a stretched ligament he received in an accident. He's a farmer with seven children and has field work that wasn't finished. Let's cheer him up; Noah Mast has been taking Chemo and is to continue on it for quite a period of time yet. Mail would be welcome; A hearty thank you to each & everyone for all the help, cards, letters, grocery showers, sunshine boxes, scrap books, prayers, & visits while Marvin was so sick & since he had his kidney transplant.

The audience for these appeals is the Oak Glen Old Order Amish women, who respond by showering other church members with cards, letters and scrapbooks containing pictures of flowers and scenery and encouraging quotes. For these women, the circle letter becomes a site where the everyday of their community and the sacred of their church community collapse into one entity, thanks to the women who write letters. When she is writing under the direction of the church newsletter, the Oak Glen Old Order Amish woman is writing to and for community members. When she is writing under the direction of circle letter members' communal values, she is writing to and for the church. Thus, the circle letter ritual serves both domestic and sacred purposes.

Because the male spouses of the Oak Glen circle letter members do not contribute letters, they are not overtly recognized as participants in the circle. However, the women use their husbands' names on the list for identification purposes, and the men also read the letters addressed to their wives. The men report that they often look forward to the arrival of the letters as much as their spouses do. Both men and women take note of which woman on the list sent the packet on its way the fastest. Clearly, these women play important roles as communal liaisons, since they not only maintain social ties with each other but also with the men who read the letters and, indeed, any community person who picks up the letters to read.

Since the circle letter—in fact, any letter—is freely shared with anyone who desires to read it., it becomes integral to the well-being of the broader community. Thus, while the letter serves a real audience positioned in a rhetorical circle, it also serves radiating circles of communication in whichever geographical location the letter resides at the moment.

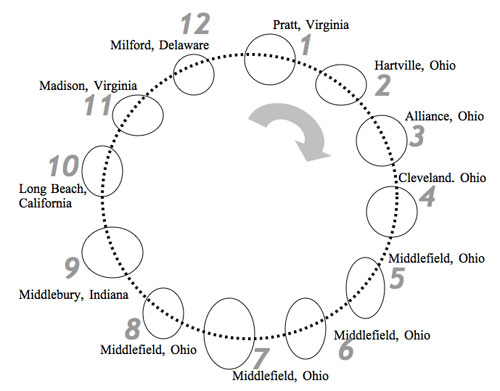

Fig. 3. The larger rhetorical circle of female members writing and reading letters.

When it arrives by postal service in Virginia, for example, it is read not only by the member of the circle, but also by the spouse and anyone else who may enter that home. Or it may be taken by the member to an event so that it can be read by other interested parties. The entire community is bound together by the letter in these various circles. Contemporary Oak Glen communal relationships are made material through female penmanship.

Although, on a practical level, the number assigned to each member of the circle letter facilitates identification, it more importantly represents the rhetorical position each woman occupies in the circle (Fig. 3). These women neither meet in real time nor occupy space in a physical circle. A member addresses the entire group, the circle, when she writes her letter. Although member number 10 may address member number 1 in a letter, members 2 through 9 are looking on, reading, participating and positioning themselves in the circle as target audience as well. The letter does not exist temporally. Rather, it rhetorically positions and provides location for the target audience during a member's reading of the letter—which is the moment when the circle is activated. Community is evoked every time an Oak Glen community member, or someone welcomed into the community member's home, reads the circle letter.

The Old Order Amish and Conservative Mennonite women participate in the ritual of circle letter inside personal spaces formed by their communal interactions. However, the same ritual that binds them together in community also sets them apart as women within the Oak Glen community, separate from the Oak Glen men and their more public sphere. In sustaining communal relationships, the circle letter also sets the entire community of Oak Glen men and women apart from other communities in the surrounding public sphere. The circle letter ritual serves to bind them together and to separate them from others.

Adhering to the circle letter ritual is one way that the Oak Glen women validate themselves in light of the community's expectations. The writing practices are communal means to communal ends. The circle letter ritual is sanctioned by both community and church and reinforces the Oak Glen women's commitment to each other and to their beliefs, in an attempt to preserve a cohesive community.