When readers of the Journal of the Center for Mennonite Writing hear the name “David Wright,” they probably think of the Mennonite poet, well-known for his piece “A New Mennonite Replies to Julia Kasdorf” (Lines 17-18), which wryly responds to some of the tropes of Mennonite literature listed in Jeff Gundy’s “How to Write the New Mennonite Poem.” But most sports fans probably think of the New York Mets’ all-star third baseman, who has been one of the best players in baseball over the past decade.

When I was asked to edit this issue of JCMW on sports, I immediately thought about David Wright. “A New Mennonite Replies to Julia Kasdorf” has been one of my favorite Mennonite poems since I first encountered it in Ervin Beck’s Mennonite Literature course at Goshen College in the spring of 2001, and these fond thoughts were heightened when I saw Wright do a hilarious impression of the ethicist Stanley Hauerwas at the 2002 Mennonite/s Writing conference, and when I chatted with him at the 2012 conference. But I must admit that, as a lifelong Mets fan, since 2004 when David Wright made his major league debut the signifier “David Wright” has most prominently denoted for me the third baseman, my favorite player. When I check the Mets box score my first thought is “Did they win?” and my second thought is “How many hits did Wright have?” He is on my mind nearly every night of the summer.

Of course both “David” and “Wright” are rather common names. Thus it is not surprising that there are two David Wrights who are famous enough to have come to my attention. But I find the synchronicity of their name meaningful because it brings together two things that I love, writing and sports, which many people think are polar opposites. When I tell an academic colleague that I am a sports fan, I cannot tell you how many times the response is a negative one. These responses range from looks of bemused disgust to dismissive questions such as “What’s the point? It’s only a game!” to angry diatribes about how athletes are overpaid to laughter because they assume that I must be joking. Judging from discussions with other sports-loving coworkers, I am not alone in receiving these reactions. In this way of thinking, writing is a noble intellectual pursuit epitomizing the acme of culture, and sports are a trivial and yet horrifyingly over-influential activity followed by the same kind of people who watch Here Comes Honey Boo Boo or Jersey Shore. And it is true: there are problematic elements of the sports world. The athletes do get paid way too much, cities invest hundreds of millions of dollars in new stadiums instead of in social services, some sports (notably American football) result in debilitating injuries, and, if you are doing it right, watching your favorite team play is much more of a stressful experience than an enjoyable one.

Nevertheless, this stereotype of sports as being unworthy of consideration by thoughtful persons is problematic despite its enduring presence. Two of David Wright’s poems show why the intersection between writing and sports is one worth paying attention to.

In “My Friend at Firestone Asks about Poems” (A Liturgy 26), the speaker’s blue collar friend asks if he has any poems about manual labor or “how good a football game looks on Sunday” after working a twelve-hour night shift. The description of watching football as a mode of relaxation occupies half of the poem, showing its importance in working class life. The friend assumes that literature has nothing relevant to say about his experiences. The poem simultaneously acknowledges this assumption as a fair critique by allowing it a voice while also responding to the critique by being a powerful poem about the working class in general and sports as a refuge that can offer a poetic tranquility in particular. The reader is able to feel the soft “recliner” and taste the cold beer being drunk while the game goes on that the speaker’s friend wants a poem about. The poet’s willingness to provide it shows that both literature and sports are avenues for transcending class divides and other social barriers, which is something worth acknowledging for those of us in what should be a socially conscious Anabaptist milieu. When I watch a Mets game, I do not just feel connected to the team, I feel connected to all of its other fans and to the city where the team plays even though I have not lived there in over a decade. I can have an enjoyable conversation about sports with a complete stranger just as I can about the short story in the latest issue of the New Yorker. It is precisely because our culture is so sports saturated and because sports serve as a common bond across class and ethnic (and, increasingly, gender and sexuality) divisions that we should seek out thoughtful writing about sports in order to better understand their appeal.

A poem from Wright’s first collection acknowledges this appeal. In “Lines from the Provinces,” which is about the difficulty of writing poetry and how this struggle is worthwhile because it sometimes leads to the sublime, the speaker describes sitting at a church dinner with “boys who played / on my little league teams, all good athletes / who would take my spots on the baseball fields” once they reached “high school” (Lines 80). The inclusion of these lines is striking because they show that there is something worth chasing in sports just as there is in the act of writing, as the speaker’s baseball failures are used as a metaphor to describe his inability to produce poems that his academic advisor appreciates. Both include moments of aesthetic beauty that can lift us to a higher plane of existence for a moment even as we remain ensconced in the world. Sports fans will tell you that a great play such as Jermaine Jones’s long-range goal for the U.S.A. against Portugal in this past summer’s World Cup, or LeBron James speeding down the court to block an opponent’s shot from behind, or David Wright lacing a line drive double into the right-centerfield gap is itself a kind of poem.

When I think about “David Wright,” what they each do is not as disparate as the two activities may seem. There is a narrative to sports which lends itself to the contemplation of the successes and tragedies of human existence just as good writing does. The pieces in this issue on sports acknowledge this confluence between sports and writing and show why it is worth exploring.

Todd Davis’s essay “Lessons” examines the values taught by the football-mad culture of his Midwestern boyhood. The game is initiation rite, escape, and violent spectacle. Davis explores how this spectacle is simultaneously addicting and disturbing as he and his teammates try to find their way into adulthood.

Chip Frederick’s essay “Growing Up Mennonite, Growing Up Hawkeye” describes how being a sports fan went hand-in-hand with being a Mennonite in his childhood. This fandom was one way Mennonites could acceptably interact with the outside world in the 1960s. Frederick shows that belonging to a community of fans, in this case of the Iowa Hawkeyes, can offer a kind of sustenance in fellowship that is also found in church.

Two sets of three baseball poems serve as counterweight to the two football essays. Carl Haarer’s triptych of poems chronicles scenes from the Boston Red Sox’s improbable 2004 postseason run. “The Idiot Red Sox Will Rise!” has a very “upside-down kingdom” feel to it in its use of the trope of the Red Sox as marginalized misfits who nevertheless triumph. “Previewing the World Series” uses religious language (“the old testament of loss and pain”) to help describe why sports have such a hold on us: there is something mystical about baseball that inspires devotion in fans, as illogical as that devotion might seem. And “Times Square Poem 3AM” offers the image of the baseball fan as urban walker, as flâneur that is also found in Jesse Nathan’s “The Sweep.” Nathan’s three poems pay homage to baseball’s enduring presence in American life as it sits in the background of scenes from both the speaker’s life and the broader global community. Baseball brings solace in the face of being turned down for a date (“In the fall of 1960, my father turned sixteen”) or the death of a beloved celebrity (“July 11”), and brings spontaneous joy as the hometown nine vanquish their opponents for the third game in a row in “The Sweep.”

One common theme in the work of Davis and Nathan is the intersection between sports and models for masculinity. Whether it is knowing how to take a hit in Davis’s essay or examining Babe Ruth’s largesse in Nathan’s “July 11,” sports offer ways of being a man that the authors’ work interrogates, searching for better ways of living. Similarly, Melanie Zuercher’s “Sports, Me, Title IX, and the World Cup” questions American society’s assumptions about gender and sports in its description of her growing obsession with soccer, which in the United States is played much more successfully by women than men. Zuercher uses her personal story to map the gains in sports women have achieved over the past forty years in American society as a whole. The essay also illustrates how sports fandom itself is changing due to the rise of social media. Like the other pieces in the issue, it shows how our passion for sports may be difficult to explain to non-sports fans, but is somehow life-giving anyway.

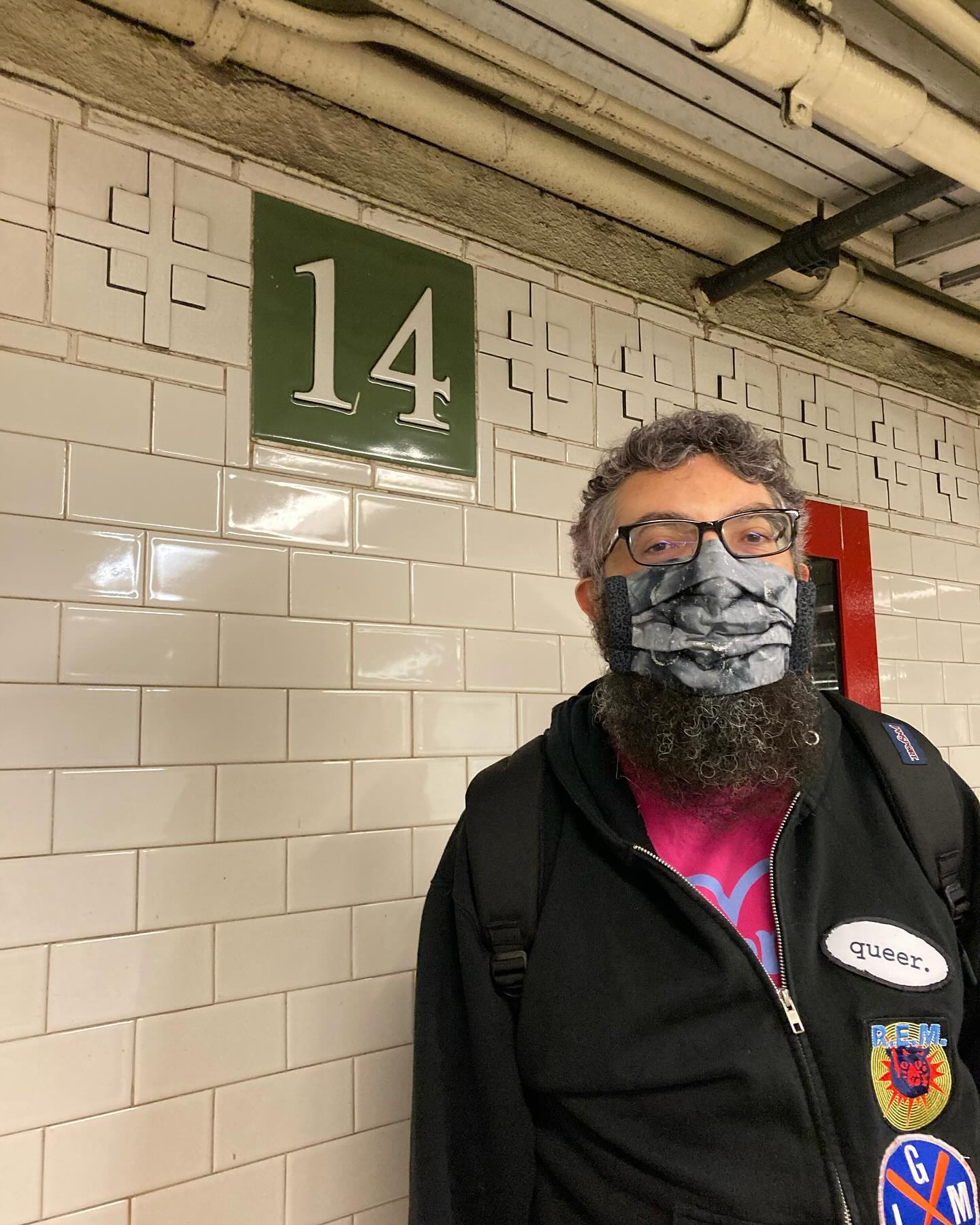

Daniel Shank Cruz (they/multitudes) is a genderqueer bisexual disabled boricua who grew up in the Bronx and Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Multitudes is the author of a book of literary criticism, Queering Mennonite Literature: Archives, Activism, and the Search for Community (Penn State University Press, 2019), and a hybrid memoir/literary critical text, Ethics for Apocalyptic Times: Theapoetics, Autotheory, and Mennonite Literature (Penn State University Press, 2024). With James Knippen, they are the co-author of It Breaks Your Heart: Haiku and Senryu on the 2023 New York Mets (Redheaded Press, 2024). Their writing has also appeared in venues such as Acorn, Blithe Spirit, Failed Haiku, Frogpond, Kingfisher, Modern Haiku, Religion & Literature, Rhubarb, and numerous essay collections. Multitudes also maintains the three Mennonite/s Writing Bibliographies at mennonitebibs.wordpress.com. Visit them at danielshankcruz.com.

Daniel Shank Cruz (they/multitudes) is a genderqueer bisexual disabled boricua who grew up in the Bronx and Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Multitudes is the author of a book of literary criticism, Queering Mennonite Literature: Archives, Activism, and the Search for Community (Penn State University Press, 2019), and a hybrid memoir/literary critical text, Ethics for Apocalyptic Times: Theapoetics, Autotheory, and Mennonite Literature (Penn State University Press, 2024). With James Knippen, they are the co-author of It Breaks Your Heart: Haiku and Senryu on the 2023 New York Mets (Redheaded Press, 2024). Their writing has also appeared in venues such as Acorn, Blithe Spirit, Failed Haiku, Frogpond, Kingfisher, Modern Haiku, Religion & Literature, Rhubarb, and numerous essay collections. Multitudes also maintains the three Mennonite/s Writing Bibliographies at mennonitebibs.wordpress.com. Visit them at danielshankcruz.com.