1.

In her 2017 essay "The Scope of This Project," one of the most important pieces of Mennonite literary theory ever, Sofia Samatar calls for an investigation of "postcolonial Mennonite writing," which includes work by Mennonite writers from global postcolonial contexts as well as "minority writers in North America."[1] Samatar's advocacy for hybrid Mennonite identities that encompass multiple ethnicities, nationalities, cultures, theologies, geographies, and, implicitly, sexualities—which I view as a necessary addition to Samatar's concept—epitomizes intersectional, anti-oppressive ideals. When I read Samatar's essay, something clicked for me. I felt that finally the theoretical tool existed for me to begin thinking about my ethnic hybridity in helpful ways. So I apply Samatar's concept to myself here as an example of how it might be employed and as an attempt to theorize it further for others' use.

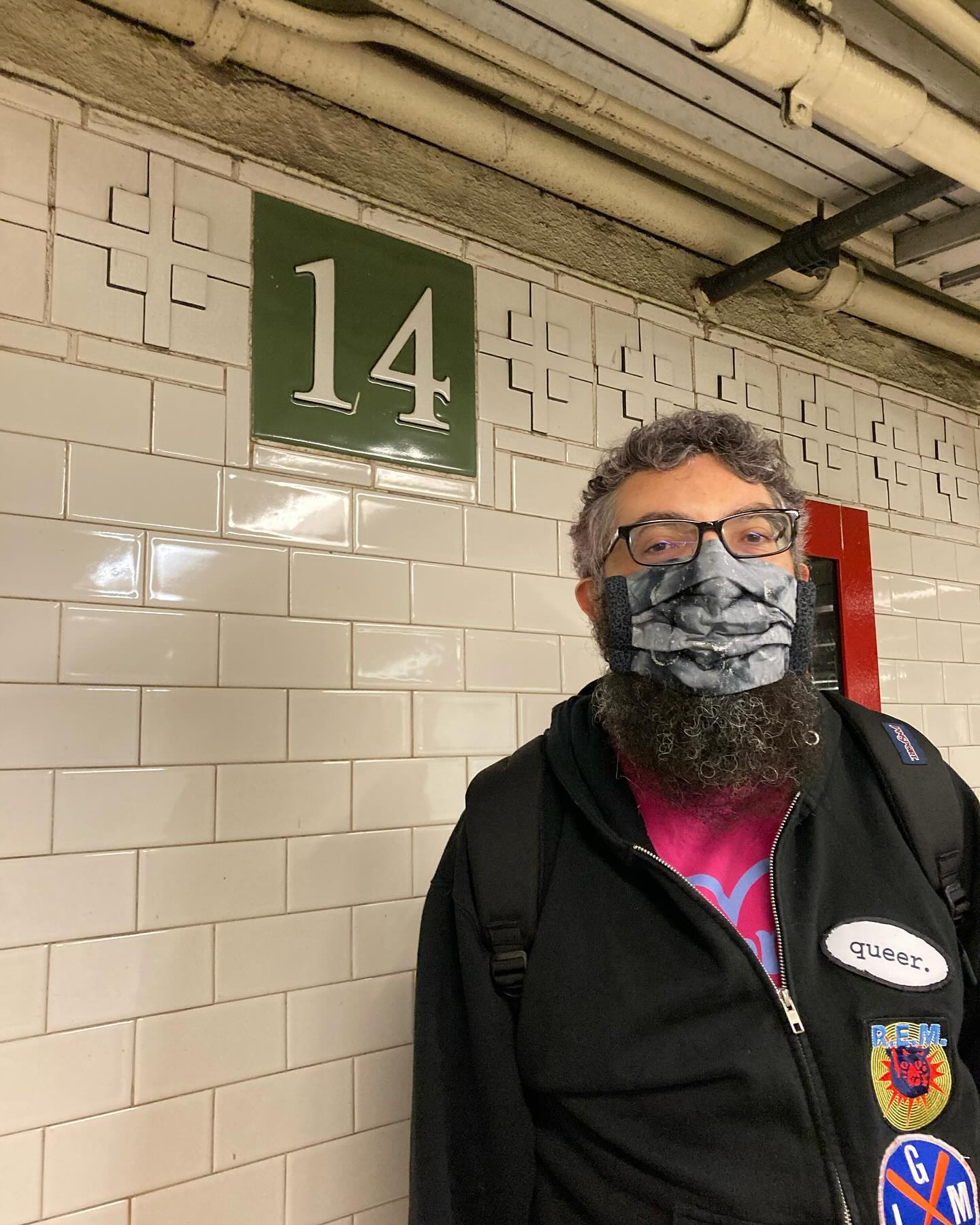

I am a queer Latinx Swiss Mennonite, but have struggled all my life to find a way to integrate these identities successfully. I have found myself switching between identities like I was putting on and taking off a set of Halloween masks depending on what context I was in. I learned what seemed like the necessity of this code-switching as a child. Growing up in the Bronx, I tried to identify as what my classmates and I then called "Spanish"[2] because I saw my Puerto Rican relatives a lot more than my Swiss Mennonite ones and realized that no one at P.S. 97 or I.S. 144 would know what a Mennonite was, anyway. I learned a lesson in sixth grade about how identity formation gets policed by others when the topic of ethnicity came up while walking in the hall between classes and I claimed to some classmates that I was Spanish.

"You're not Spanish, you're white."

"No I'm not."

"Where's your father from?"

"Puerto Rico."

"Where's your mother from?"

"Virginia."

"See? You're not Spanish."

Being what Junot Diaz calls a "halfie"[3] meant not being authentic enough to fit in, even if I wanted to. I thus learned to begin proactively hiding certain parts of my identity and highlighting others depending on my context in order to be the one defining myself rather than having others do it for me. When my family moved to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, just before I began ninth grade at Lancaster Mennonite High School it was easy for me to only be a Mennonite, setting my Puerto Rican self to the side, and likewise during my four years at Goshen College. Doing the work to discover my queer identity was an impossibility in both of these places. When I moved back to New York City for a two-year Mennonite Voluntary Service term, I was able to begin exploring my queer self and further explore my Mennonitism, though not in dialogue with one another because they felt like opposites. In graduate school in DeKalb, Illinois, I identified as bisexual, and would say I was Puerto Rican if anyone asked about my ethnicity because just like in the Bronx no one knew what a Mennonite was. My colleagues would tease me about being "the whitest Puerto Rican they knew." My Puerto Rican identity was illegible to them, and often to myself.

2.

It is only since finishing my Ph.D. that I have been able to approach my identity intersectionally. In my scholarship, I have written about my queer Mennonite identity as a result of investigating the burgeoning field of queer Mennonite literature,[4] but still have not found successful ways of integrating my Latinx self as well. I understand it less well than my Mennonite self, in part because I have a large archive—both private and public[5]—to access on my Shank side and hardly anything to access on my Cruz side.

Page 2

So this essay is an attempt to produce intersectional postcolonial Mennonite writing despite its difficulty, to work on building its archive. I am still working through my struggle to understand my Latinx self and thus cannot offer definitive answers, but I think it is necessary to write about the journey as one way of working toward and theorizing the Mennonite intersectionality that Samatar's essay envisions because, as Michele Elam posits, not only is being an ethnic hybrid "political," but so is discussing such identities.[6] I am inspired in my attempt by Samatar's work as a Mennonite person of color as well as other intersectional efforts such as Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes's theorization of the field of "queer Puerto Rican studies" that is working to become visible.[7] I view my essay as one entry within this field and within the field of Mennonite studies.

My first step when trying to understand my Latinx self has been to look for models in literature because it is an approach that has been helpful for me when trying to understand my Mennonite self, my queer self, and the intersection between these identities. Seeing myself in texts such as Jeff Gundy's Rhapsody with Dark Matter, Hanif Kureishi's The Buddha of Suburbia, and Stephen Beachy's boneyard [sic] has been invaluable.[8] La Fountain-Stokes also recognizes the power of seeing oneself reflected in other's stories, writing of the importance of personal narratives in literature by queer people of color.[9] Such narratives are included in those that Samatar hopes to see in Mennonite literature. Mennonite literature has taught me how to both take pride in my Mennonite heritage and how to question it, and it has helped me learn how to be a queer Mennonite.

3.

But there are virtually no narratives about Latinxs in Mennonite literature, and the one I am aware of, David Bergen's 2016 novel Stranger,[10] is sadly an excellent example of how far Mennonite literature still needs to go to become postcolonial. I read Stranger as a book about the U.S.'s economic imperialism and how it uses Latin America as a source of cheap, dehumanized labor. This is not Bergen's story to tell from the perspective he tells it. I am not arguing that writers may only write about their own communities or perspectives, but that it must be done cautiously. As Samatar says in an interview with Aaron Bady, merely including ethnically "diverse" characters in one's writing is not the same as writing about "marginalized people."[11] In other words, to write about such characters sensitively it is necessary for white writers to acknowledge the characters' marginalization and to write against it. Part of such sensitivity means understanding the characters' geopolitical context. This is where Stranger fails. It only tells the story of its individual characters without examining their broader societal positions. It is not intersectional, examining the interactions between class, race, and gender. Instead, Stranger tells the story of illegal immigration that North American whites want to hear: a story that ends happily for both the immigrant (the protagonist Íso does not fall victim to the judicial system and her family remains intact) and white readers (the racial Other leaves the U.S., so readers do not have to worry about them anymore). It is true that the novel portrays the white Americans who take Íso's baby as the villains, but their villainy is represented as an individual, personal failing. There is no recognition in the text that they can have their racist attitudes which lead to their racist actions without censure in their U.S. gated community because their actions take place within a broader context of systemic racism that the book does not acknowledge. I am sure that some real-life immigrant stories have happy endings like Íso's, but most do not, and the way Stranger ignores these narratives in favor of its easy, comforting one is problematic. Such a hopeful narrative might be okay for a Latinx author to write as an act of resistance, but not for Bergen. Instead of being liberatingly postcolonial, his book valorizes neoimperialism.

Page 3

I find Bergen's failure especially frustrating because the offense Stranger commits is not a new one in North American literature. At least as far back as William Styron's 1967 novel Confessions of Nat Turner, literary critics of color have been chastising white authors for their misappropriation of stories that are not theirs to write.[12] It saddens me that a Mennonite author would do such a thing. Mennonites should know better. Rudy Wiebe wrote way back in 1964 about Mennonite racism, observing that although there were some Mennonite congregations with minorities as members, these congregations were marginal within the Church and had little denominational clout.[13] On a related note, Elmer F. Suderman argues that Wapiti's hypocrisy in Wiebe's Peace Shall Destroy Many stems from its racism.[14] So discussions of race have been present in North American Mennonite literature in English from its early days. But Mennonite racism remains rampant, and it takes a psychological toll. I cannot stop feeling angry about Stranger even though I read it over a year ago. Writing about it put me in a funk for a few days and I had to step away from this essay for a while.

4.

There are few pieces of Mennonite literature by Mennonites of color in general. I know of Samatar's work, and of Katherena Vermette's work, and of Yorifumi Yaguchi's work, and of Dominique Chew's work, and that is about it.[15] In another 2017 essay, "In Search of Women's Histories: Crossing Space, Crossing Communities, Crossing Time," Samatar writes about why North American society's anti-intersectional bias makes it is difficult to mesh Mennonite identity with other ethnic minority identities. She examines Sabrina from the television show Breaking Amish, a Puerto Rican who gets adopted by a Pennsylvania Mennonite family and is thereby a Puerto Rican Mennonite in some ways. However, the show does not allow Sabrina to be a hybrid. She is either a conservative, plain Mennonite (an identity that itself gets erased by the show's title, which should more accurately be Breaking Anabaptists), or solely "Puerto Rican" once the show brings her to New York City: she is portrayed wearing hoop earrings and dressing in loud colors while interacting with her Puerto Rican family. Samatar explains that "Sabrina cannot know about Mennonite churches in Puerto Rico" or about Mennonite churches in the city, some of which are explicitly Latinx-identified. The show engages in this "racial separation" because "if Latina Mennonites exist[… e]verything's muddy," there is "cultural anarchy." Sabrina can only be "the plain, chaste Mennonite" or "the sassy, sexy Puerto Rican." Such anti-hybridity enforces "the myth of recognizable identity."[16] Samatar's analysis of the "muddiness" of having two ethnic identities is important because part of what I am seeking in the journey of the present essay is the ability for my hybrid identity to be somehow recognized and made sense of, both by myself and others. So I am perhaps seeking a self-understanding that can never exist because the broader (Mennonite) culture does not want it to exist. This difficulty is why there is space for racist Mennonite narratives such as Stranger to come into being.

Therefore, I have looked outside of Mennonite literature for possible models. For instance, I was excited to find Erika Lopez's Flaming Iguanas: An Illustrated All-Girl Road Novel Thing, which stars a half-Puerto Rican, half-German bisexual Quaker, an identity that is somewhat close to my half-Puerto Rican, half-Swiss Mennonite bisexual self. Lopez's semi-autobiographical protagonist Tomato shares my angst about my mixed ethnicity and not having queer ethnic role models to look up to. She complains that she does not feel like "a real Puerto Rican" because, like me, she does not speak Spanish. She "want[s] a Bisexual Female Ejaculatory Quaker role model" to look up to and decides that "[f]rom now on [she will] demand to be represented" in pop culture.[17] I want narratives that represent me, too, but despite the affinity between our hybrid identities on the surface, Tomato's narrative does not really speak to me. It is, frankly, just not Mennonite enough, a lack that I feel strongly because my Mennonitism is at the center of the Venn diagram of my various identities. Thus it is necessary to return to the field of Mennonite literature and further theorize how it might approach intersectionality.

Page 4

5.

In "The Scope of This Project," Samatar suggests "hymns" as a subject for global Mennonite literary analysis because they are a shared genre across Mennonite communities.[18] Food and its rituals, an important element of building community both literary and otherwise, is another area of commonality across the Mennonite diaspora calling for further theorization. What shared foodways—including theories and theologies of food, not just shared cuisines—can be found throughout the Mennonite diaspora? Is food writing another area where the postcolonial Mennonite writing archive could be enlarged? Kay Stoner highlights these intersectional possibilities in a discussion of "potlucks" and the "fellowship" they entail in both queer and Mennonite communities, so there is already a basis from which to expand this theorizing.[19] Specific foods could also be used as symbols for intersectional analysis.[20] Pork is one example that works well for my own life. From a Swiss Mennonite perspective, John L. Ruth recalls hearing stories from his father about how his family would use every bit of the pigs they would slaughter for food: chops, roasts, hams, bacon, sausage, scrapple.[21] Puerto Rican cooking also uses the entire pig. Growing up, my grandmother would make pernil (roast pork shoulder) for Christmas, and on other occasions would make pork ribs or chicharron, pieces of fatty deep-fried meat leftover from butchering the pig into specific cuts. Remaining bits of meat from these dishes were used to flavor rice and beans or pasteles. There was often a bag of pork rinds to snack on at her house between meals. The two cultures' love of pork melds when my father, who has been a part of the Mennonite community for fifty years, makes pernil for Shank family reunions. When we eat it, the fellowship it facilitates matters, not our ethnicities.

I am also intrigued by the role that the theoretical exploration of geographical spaces, whether real or imagined, can play for postcolonial Mennonite writing. Samatar names this possibility in her advocacy of the concept of "diaspora" as one that is important for such writing.[22] Her novella Fallow provides one example of such exploration. It takes place on a far planet centuries from now. A group of Mennonites have left a dying Earth and set up a colony called Fallow, thus achieving the long-held Mennonite dream of having a land of our own without interference from governments who will force us to join the military or attend school in English. They are no longer "that heart-breaking paradox: wandering farmers."[23] Unfortunately, Fallow devolves into a repressive theocracy. It is basically Wiebe's Wapiti in outer space. However, Fallow offers a liberating vision of Mennonite community for twenty-first century readers because it fully accepts queer relationships, putting the identity queer Mennonite on equal footing with the identity straight Mennonite. Fallow does not repress its members based on their sexuality or ethnicity, but based on whether or not they want to interact with non-Mennonites. Thus in its obviously negative portrayal of strict Church polity which it means for readers to reject the novella argues for a version of Mennonitism that is intersectional and open to learning from others.

On a more concrete plane, New York City is an example of a location available for theorization as a postcolonial Mennonite space. It is one context where my hybrid Mennonite identity feels at home. Numerous Mennonite writers such as Jessica Penner, Casey Plett, and Julia Spicher Kasdorf have lived there while producing work,[24] so it is already a Mennonite literary space. Both traditional ethnic Mennonite and person of color identities are on full display in Mennonite New York because for the past fifty years, the city has had a significant postcolonial Mennonite presence.[25] As noted above, the city is also a space with room for queer identities. La Fountain-Stokes theorizes the city as a queer space in his identification of the conceptual location of "Nuyorico" as represented in queer art by the Puerto Rican diaspora in the Bronx. He asserts that Nuyorico is "an intrinsically queer space," and that it is "an embedded mindscape[…,] portable."[26] Nuyorico's movability is important because its symbolic impact is transferable to global contexts, including Mennonite ones. Nuyorico can be effectively appropriated into Mennonite thought because it is "a space of liberation, tolerance, and social justice,"[27] which are also Mennonite ideals. I find this space one that I can inhabit productively as I try to define myself and mesh all of my identities. It contains an element of cosmopolitanism that has often been absent from Mennonite spaces.

Page 5

These possibilities for thinking about Mennonite intersectionality in general and myself in particular still feel tenuous to me as I finish this essay. I am not sure whether they will work. But Samatar writes in "The Scope of This Project" that postcolonial "Mennonite literature has to be created," that we must actively seek it.[28] I offer these musings as one step in this search.

[1] Sofia Samatar, "The Scope of This Project," Journal of the Center for Mennonite Writing 9, no. 2 (2017): http://www.mennonitewriting.org/journal/9/2/scope-project/#all.

[2] Juana María Rodríguez notes the ubiquity of this term for Latinxs on the East Coast up through the 1980s no matter what our national background in Sexual Futures, Queer Gestures, and Other Latina Longings (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 104.

[3] See Junot Diaz, "How to Date a Browngirl, Blackgirl, Whitegirl, or Halfie," in Drown (New York: Riverhead Books, 1996), 141-49.

Page 6

[4] See, for instance, Daniel Shank Cruz, "Reading My Life in the Text: Adventures of a Queer Mennonite Critic," Journal of Mennonite Studies 34 (2016): 280-86.

[5] Aside from the fact that I have more family documentation on my Shank side because my grandfather Lester C. Shank was both a genealogy and a photography buff who labelled his work meticulously and saved everything, I am also able to read about my Mennonite family heritage in books. There is a discussion of my ancestor Hans Herr in the first volume of the Mennonite Experience in America series, Richard K. MacMaster, Land, Piety, Peoplehood: The Establishment of Mennonite Communities in America 1683-1790 (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1985), 81-83, and my parents, Jesus and Miriam Cruz, are discussed throughout Richard K. MacMaster, Mennonite and Brethren in Christ Churches of New York City (Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press, 2006). Such references give me a sense of belonging within the Mennonite tradition that I am still looking for in the Puerto Rican tradition.

[6] Michele Elam, The Souls of Mixed Folk: Race, Politics, and Aesthetics in the New Millenium (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011), 6.

[7] Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes, Queer Ricans: Cultures and Sexualities in the Diaspora (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), xiv.

[8] Jeff Gundy, Rhapsody with Dark Matter (Huron, OH: Bottom Dog Press, 2000); Hanif Kureishi, The Buddha of Suburbia (New York: Penguin Books, 1990); Stephen Beachy, boneyard (Portland, OR: Verse Chorus Press, 2011).

[9] La Fountain-Stokes, Queer Ricans, 103.

[10] David Bergen, Stranger (Toronto: HarperCollins, 2016). Novels such as Rudy Wiebe's The Blue Mountains of China (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1970) and Miriam Toews's Irma Voth (New York: Harper, 2011) include Mennonites living in Latin America, but these characters identify ethnically as Mennonites, not as Latinxs.

[11] Sofia Samatar, "Interview: Sofia Samatar," by Aaron Bady, Post45, 18 December 2014, http://post45.research.yale.edu/2014/12/interview-sofia-samatar/.

[12] See John Henrik Clarke, ed., William Styron's "Nat Turner": Ten Black Writers Respond (Boston: Beacon Press, 1968).

[13] Rudy Wiebe, "For the Mennonite Churches: A Last Chance," 1964, in A Voice in the Land: Essays by and About Rudy Wiebe, ed. W.J. Keith (Edmonton: NeWest Press, 1981), 28. Of course some (i.e., not me because I do not feel in a position to do so, but I recognize the validity of such critiques if they exist: it is the right of the oppressed rather than the oppressor to define their oppression) might accuse Wiebe of the same fault I accuse Bergen of regarding Wiebe's fictional portrayals of Indigenous Peoples, but Wiebe's essay at least shows an awareness of racial issues that Bergen's novel does not.

[14] Elmer F. Suderman, "Universal Values in Rudy Wiebe's Peace Shall Destroy Many," 1965, in Keith, A Voice in the Land, 72.

[15] Aside from Samatar's fiction, a piece of which I discuss below, see, for instance, Katherena Vermette, The Break (Toronto: House of Anansi Press, 2016); Yorifumi Yaguchi, The Poetry of Yorifumi Yaguchi: A Japanese Voice in English (Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 2006); and Dominique Chew, The Meaning of Grace (Goshen, IN: Pinchpenny Press, 2015).

[16] Sofia Samatar, "In Search of Women's Histories: Crossing Space, Crossing Communities, Crossing Time," Journal of Mennonite Writing 9, no. 3 (2017): https://mennonitewriting.org/journal/9/3/search-womens-histories-crossing-space-crossing-co/#all.

[17] Erika Lopez, Flaming Iguanas: An Illustrated All-Girl Road Novel Thing (New York: Simon & Schuster Editions, 1997), 241, 29, 251.

[18] Samatar, "The Scope of This Project."

[19] Kay Stoner, "How the Peace Church Helped Make a Lesbian Out of Me," Mennonot (Fall 1994), 10, http://www.keybridgeltd.com/mennonot/Issue3.pdf. Malinda Elizabeth Berry, "The Gifts of an Extended Theological Table: MCC's World Community Cookbooks as Organic Theology," in Table of Sharing: Mennonite Central Committee and the Expanding Networks of Mennonite Identity, ed. Alain Epp Weaver (Telford, PA: Cascadia Publishing House, 2011), 284-309, could be another foundational text for postcolonial Mennonite literary food theorizing because of its discussion of how MCC's cookbooks work to acknowledge Mennonitism's international contexts.

[20] My thought here is inspired by Ervin Beck's investigation of possible archetypes for use in Mennonite literary criticism, most notably that of "Menno in the molasses barrel," in "The Signifying Menno: Archetypes for Authors and Critics," in Migrant Muses: Mennonite/s Writing in the U.S., ed. John D. Roth and Ervin Beck (Goshen, IN: Mennonite Historical Society, 1998), 49-67, especially 55-56.

[21] John L. Ruth, Branch: A Memoir with Pictures (Lancaster, PA: TourMagination/Harleysville, PA: Mennonite Historians of Eastern Pennsylvania, 2013), 12.

[22] Samatar, "The Scope of This Project."

[23] Sofia Samatar, Fallow, in Tender: Stories (Easthampton, MA: Small Beer Press, 2017), 260.

[24] Penner and Kasdorf discussed the city's effects on their writing in a panel, "The Quest: Being Female, Mennonite, and an Artist in New York City," at the Crossing the Line: Women of Anabaptist Traditions Encounter Borders and Boundaries conference at Eastern Mennonite University in Harrisonburg, Virginia, on 24 June 2017.

[25] See MacMaster, Mennonite and Brethren in Christ Churches of New York City, especially chapter eleven, for a discussion of the significant roles played by Latinxs and African Americans in Mennonite New York.

[26] La Fountain-Stokes, Queer Ricans, 133, emphasis in the original.

[27] Ibid., 132.

[28] Samatar, "The Scope of This Project."

Bibliography

Beachy, Stephen. boneyard. Portland, OR: Verse Chorus Press, 2011.

Beck, Ervin. "The Signifying Menno: Archetypes for Authors and Critics." In Migrant Muses: Mennonite/s Writing in the U.S., edited by John D. Roth and Ervin Beck, 49-67. Goshen, IN: Mennonite Historical Society, 1998.

Bergen, David. Stranger. Toronto: HarperCollins, 2016.

Berry, Malinda Elizabeth. "The Gifts of an Extended Theological Table: MCC's World Community Cookbooks as Organic Theology." In Table of Sharing: Mennonite Central Committee and the Expanding Networks of Mennonite Identity, edited by Alain Epp Weaver, 284-309. Telford, PA: Cascadia Publishing House, 2011.

Chew, Dominique. The Meaning of Grace. Goshen, IN: Pinchpenny Press, 2015.

Clarke, John Henrik, ed. William Styron's "Nat Turner": Ten Black Writers Respond. Boston: Beacon Press, 1968.

Cruz, Daniel Shank. "Reading My Life in the Text: Adventures of a Queer Mennonite Critic." Journal of Mennonite Studies 34 (2016): 280-86.

Diaz, Junot. "How to Date a Browngirl, Blackgirl, Whitegirl, or Halfie," In Drown, 141-49. New York: Riverhead Books, 1996.

Elam, Michele. The Souls of Mixed Folk: Race, Politics, and Aesthetics in the New Millenium. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011.

Gundy, Jeff. Rhapsody with Dark Matter. Huron, OH: Bottom Dog Press, 2000.

Keith, W.J., ed. A Voice in the Land: Essays by and About Rudy Wiebe. Edmonton: NeWest Press, 1981.

Kureishi, Hanif. The Buddha of Suburbia. New York: Penguin Books, 1990.

La Fountain-Stokes, Lawrence. Queer Ricans: Cultures and Sexualities in the Diaspora. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Lopez, Erika. Flaming Iguanas: An Illustrated All-Girl Road Novel Thing. New York: Simon & Schuster Editions, 1997.

MacMaster, Richard K. Land, Piety, Peoplehood: The Establishment of Mennonite Communities in America 1683-1790. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1985.

---. Mennonite and Brethren in Christ Churches of New York City. Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press, 2006.

Rodríguez, Juana María. Sexual Futures, Queer Gestures, and Other Latina Longings. New York: New York University Press, 2014.

Ruth, John L. Branch: A Memoir with Pictures. Lancaster, PA: TourMagination/Harleysville, PA: Mennonite Historians of Eastern Pennsylvania, 2013.

Samatar, Sofia. Fallow. In Tender: Stories, 206-61. Easthampton, MA: Small Beer Press, 2017.

---. "In Search of Women's Histories: Crossing Space, Crossing Communities, Crossing Time." Journal of Mennonite Writing 9, no. 3 (2017): https://mennonitewriting.org/journal/9/3/ search-womens-histories-crossing-space-crossing-co/#all.

---. "Interview: Sofia Samatar." By Aaron Bady. Post45, 18 December 2014, http://post45.research.yale.edu/2014/12/interview-sofia-samatar/.

---. "The Scope of This Project." Journal of the Center for Mennonite Writing 9, no. 2 (2017): http://www.mennonitewriting.org/journal/9/2/scope-project/#all.

Suderman, Elmer F. "Universal Values in Rudy Wiebe's Peace Shall Destroy Many." 1965. In Keith, A Voice in the Land, 69-78.

Stoner, Kay. "How the Peace Church Helped Make a Lesbian Out of Me." Mennonot, Fall 1994, 10-12, http://www.keybridgeltd.com/mennonot/Issue3.pdf.

Toews, Miriam. Irma Voth. New York: Harper, 2011.

Vermette, Katherena. The Break. Toronto: House of Anansi Press, 2016.

Wiebe, Rudy. The Blue Mountains of China. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1970.

---. "For the Mennonite Churches: A Last Chance." 1964. In Keith, A Voice in the Land, 25-31.

Yaguchi, Yorifumi. The Poetry of Yorifumi Yaguchi: A Japanese Voice in English. Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 2006.

Daniel Shank Cruz (they/multitudes) is a genderqueer bisexual disabled boricua who grew up in the Bronx and Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Multitudes is the author of a book of literary criticism, Queering Mennonite Literature: Archives, Activism, and the Search for Community (Penn State University Press, 2019), and a hybrid memoir/literary critical text, Ethics for Apocalyptic Times: Theapoetics, Autotheory, and Mennonite Literature (Penn State University Press, 2024). With James Knippen, they are the co-author of It Breaks Your Heart: Haiku and Senryu on the 2023 New York Mets (Redheaded Press, 2024). Their writing has also appeared in venues such as Acorn, Blithe Spirit, Failed Haiku, Frogpond, Kingfisher, Modern Haiku, Religion & Literature, Rhubarb, and numerous essay collections. Multitudes also maintains the three Mennonite/s Writing Bibliographies at mennonitebibs.wordpress.com. Visit them at danielshankcruz.com.

Daniel Shank Cruz (they/multitudes) is a genderqueer bisexual disabled boricua who grew up in the Bronx and Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Multitudes is the author of a book of literary criticism, Queering Mennonite Literature: Archives, Activism, and the Search for Community (Penn State University Press, 2019), and a hybrid memoir/literary critical text, Ethics for Apocalyptic Times: Theapoetics, Autotheory, and Mennonite Literature (Penn State University Press, 2024). With James Knippen, they are the co-author of It Breaks Your Heart: Haiku and Senryu on the 2023 New York Mets (Redheaded Press, 2024). Their writing has also appeared in venues such as Acorn, Blithe Spirit, Failed Haiku, Frogpond, Kingfisher, Modern Haiku, Religion & Literature, Rhubarb, and numerous essay collections. Multitudes also maintains the three Mennonite/s Writing Bibliographies at mennonitebibs.wordpress.com. Visit them at danielshankcruz.com.