(The Setting is the home office of Dr. E. G. Kaufman, with desk, swivel chair, file cabinet, bookcase, and hall tree. Books, files, and papers are strewn everywhere. Telephone and typewriter on the desk.

(The telephone rings four or five times. Kaufman comes in hurriedly, wearing hat and sweater. He answers the telephone, reaching across to put his hat on the rack.]

Hello! . . . Yes, this is Grandpa. . . . No I haven't forgotten. Four o'clock. (Looks at wrist watch.) Two hours from now. Do you have a tape recorder or do you want to use mine? . . . And you want to talk about what? . . . Okay, then. I'll be ready for you. (Hangs up abruptly.)

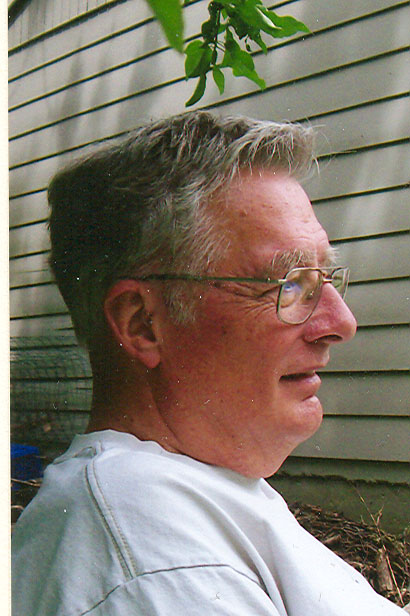

(Notices audience, acknowledges them with a nod, moves to take off sweater and hang up.) That's my grandson, Fred. Good boy. A sophomore at college. He has an oral history assignment in American history. Wants to know what "big changes" I've seen in my lifetime. In my lifetime--seventy years. He hopes we can cover it in about an hour. Humph!

What can you tell the younger generation about the way things were? How can you pass on a heritage?

A year ago Fred wouldn't even talk to me. I had gone over to his room at Goering Hall. He wasn't there, but the door was open so I went in. I was shocked. Up on the wall he had this big picture of a naked woman. It was . . . (Begins to gesture a description, but waves his arm in disgust.) I don't need to describe it to you. Well, I tore that picture down and wrote him a note to see me about it. In less than an hour he was right here in this room, madder than a wet hen.

"Give me that picture back! It's my private property! And my private room! You don't have any right to come in and take things off my wall! You're not President of Bethel College any more! And even the president can't do something like this! Who do you think you are?"

"This is Bethel College and you are my grandson, I told him. "I'll make you a deal. You can take any picture off any wall in my house in exchange. Whatever you like. But I won't give you that naked woman back."

"You are living in a different world, Grandpa," he said. "You are OUT OF TOUCH!" He stomped out of here and slammed the front door so hard it shook the whole house. Maybe this interview is his peace offering. We'll see.

Where can I start with the big changes? I grew up in a rural Mennonite community where people cared about how other people lived--and not only their own grandchildren. I remember a big argument about some members who supposedly stole some oil. There was a damaged railroad oil car left on the Missouri Pacific tracks over by Pioneer Schoolhouse. The oil started leaking out of the car into the ditch. Some of the nearby farmers came out with barrels and set them under there and got oil. Was that stealing? Some church members--some who hadn't got any oil--brought it up to the church board. Those fellows stole oil. They ought to make it right with the Missouri Pacific Company. The church should make them do it.

"Hold on here, now!" said the oil men. "You ought to thank us for saving something from going to waste. We didn't do anything wrong. Anyhow, our accusers don't have clean hands. Some of them have bought life insurance. Let the church deal with that first!"

We Mennonites weren't supposed to have insurance. We should have faith in God and in our people to take care of our needs. Once everyone got insurance they'd start feeling self-sufficient and proud. They wouldn't depend on God to protect them. They wouldn't need their fellow man any more.

So we had these two groups. The oil stealers and the insurance buyers. Who were the sinners? The church needed to deal with such things. It was the main moral authority in the community. That's the way it was.

But nowadays? Everybody does what's right in their own eyes and nobody is supposed to interfere. We've lost something, haven't we? How can one get the young people to see they aren't a law unto themselves? Mind you, when I was young I criticized the church for all it was worth. They were narrowminded, I thought. They got all excited about unimportant things. Like whether to have a piano in church, whether men and women could sit together, and so on. When I grow up and have a chance to speak in official meetings, I said, I'll really tell them off. I had a lot to learn.

We had a sense of community in those days. I knew I was a Mennonite from the beginning. A Swiss-Volhynian Mennonite. And I knew there were different people on all sides of us. People who spoke different, had strange customs, and who our young people would never dare get married to.

Here, let me show you. I grew up in McPherson County, Kansas.

(He finds a yardstick, gets the hall tree beside him, throws his sweater from the hall tree onto the chair.)

Say this hall tree is the Turkey Creek, flows north to south, of course not so straight. This yardstick is the Missouri-Pacific Railroad which angled toward the northwest--from Moundridge to McPherson and from there . . . all the way out to the Pacific Ocean or China as far as I knew. My family lived here in this triangle. Across the Turkey Creek over there were the Low German Hoffnungsau people. The other direction across the railroad was an even bigger group of Low Germans, the Alexanderwohlers. I used to climb up the windmill at our farm, about here, and look out across the Turkey Creek. What must it be like out there--in the land of Philistines? Do you think my grandson will be interested in that kind of history? He ought to.

I went to grade school at Pioneer schoolhouse, here right along the Missouri-Pacific. There were three kinds of people in school--we Schweizers, the Low Germans, and a few Americans whose farms hadn't been bought out by the Mennonites yet. The Americans spoke the English language at home. We spoke German.

At Pioneer School I had a chance to test the values I learned at home and in church. Take the peace issue for example. We Mennonites were pacifists. We followed Jesus' teaching to love our enemies, so we didn't go to war. Our Anabaptist forefathers suffered a lot for this conviction. Then in the 1870s, seventeen years before I was born, we left Russia and came to America for the freedom to live our convictions.

My test at Pioneer School was Pete Durst, one of the American kids. For some reason, Pete took special delight in tormenting me. He'd punch me, wrestle around with me, and call me a "Russian." He was bigger than me, but I could run faster.

One cold winter day Pete came into the schoolhouse where we had a pot-bellied stove in the middle of the room. He backed up to this stove and warmed himself. (EG backs up to the hall tree, now a stove.) I was just sitting over there on the side watching. Soon I noticed that the back of his pants, still wet from the snow, started to smoke. I didn't want to tell him about it, because he had been mean to me. I distinctly remember thinking at that moment that a people of peace should love their enemies and be good to them. But there I sat. Soon there were holes in the seat of his pants, he smelled the smoke, and he jumped around and beat at it with his hand. [EG acts it out.] I finally went over and helped him. But I knew I had compromised my convictions.

What would Jesus have done, I thought. Would he have gone over right away and told Pete he was too close to the stove? Then Pete would have told Jesus, "Shut up and mind your own business. I can take care of myself!" It's not easy to do good to those who persecute you. At least it wasn't easy for me, a seven-year old Schweizer boy who had to get along with the big Americans. But give me this much credit. I knew the difference between right and wrong. I thought about what Jesus wanted. Do young people do that today?

It was about that time that the Spanish-American war broke out. I remember when my Grandpa Kaufman came over to talk about it. Grandpa Kaufman, now there was a man who could get his values across to the younger generation, without even trying. He had been over to town--Moundridge--and he heard lot of war talk there. "They say the military draft is coming. My boys . . . . . . . might have to go to the army." "But they promised us exemption when we immigrated," said my father. "They say in town that a new conscription law overrides any promises," said Grandpa. "We're going to have to start looking into another place to live. Maybe Canada or Argentina. . . . We Mennonites will leave America before we get into their killing machine!" I could tell from the set of his jaw that he really meant it. Right there I learned more than in six months of Sunday School classes.

I had a hero when I was young. Nowadays they don't have heroes. The best they can do is "role models." My hero was Andrew Schrag, the first one in our small community to get a college education. He was my first German schoolteacher. Backthen we had English school for five months, and then German school for two or three months. They called the German school the "Black College."They never painted the boards and the building turned black. So it was the "Black College."

I was just a little tyke and at the end of the year had to give this recitation that began, "Das Hundlein bellt Wauwau, Das Katzlein schreit Meouw, Meouw . . ." (The little dog hollers bow-wow, the little cat cries meow-meow.) In front of all those people, could hardly get through it. But teacher Andrew Schrag took me when I was done, put his hand on my head, patted me and escorted me back to my seat. I felt so good that he approved.

Every year when Andrew Schrag came home from college for summer I would watch him closely. I wanted to be educated, even if some older people said higher education wasn't for us Mennonites. To go to Bethel College, that was almost like going to the moon now. Then Andrew Schrag got even more daring. He got engaged to a Low German girl from across the tracks. Margaret Richert.

I remember one harvest time when I was working so hard in the hot sun and in the dirt, Andrew Schrag drove by our place with a load of wheat and wearing a white shirt. My father said to me, "See, you get an education and you don't have to work hard. You can drive around in a white shirt." Father didn't mean it for a compliment. But I wanted to be like Andrew Schrag.

Then my hero went too far. He attended Johns Hopkins University in the East and met another girl. He broke his engagement to Margaret Richert. To break the Verlobung--that was serious. Almost as bad as divorce. And the Richerts--they were one of the most prominent Low German families. What would those people think of us? My grandfather Schrag came over to our house crying, [EG mocks a strong Swiss-Volhynianaccent] "Look what's happening to us in America here. How worldly we get! See what comes from going to college? We chase after success. We forget the humble and simple ways of our forefathers." I tell you, the Andrew Schrag incident ruined the Schrags for Bethel.

Did we get too proud, those of us who went to college? My father let me go, but he would straighten me out when I came back home too smart with all my higher knowledge. For instance, one weekend I came home and told my younger brothers to eat their lettuce at the meal because lettuce had iron. They needed iron. At the next meal everybody had food on their plates but on my plate was a bunch of old nails. Fathersaid, "Since Ed believes in iron, we will let him eat iron. You others can eat the regular food." Of course they let me eat then, but I was put in my place.

I have nothing against humility and simplicity--good Mennonite virtues. But they can also be twisted into an excuse for ignorance and narrowness. Even as a student I was accused of being too aggressive. My big disappointment in college was not getting on Bethel's debate team. Five or six of us tried out, but only four could make it. I knew I was a good debater. I didn't find out why I wasn't chosen until years later when J. W. Kliewer--he was college president--published his Memoirs. I have that book here somewhere. Here it is, yes, on page 109, second paragraph. President Kliewer wrote about that debate team selection.

"For years I was watching his career. (That refers to me.) I recall when he was still an undergraduate at Bethel College, that out of a number of three judges choosing a representative for our school in a debate, I was the one who pushed Ed. G.Kauffman. The other two men were not certain that he would make us a good man. One of the men stated that Kaufman was too insistent. I answered, 'That is what we want a debater to be. But the man responded, 'He might prejudice the judges against him.' "

So there you have it. I lost out two to one. But the man on my side was the college president, J. W. Kliewer. A president has to know something about leadership. You don't inspire people to great deeds and noble sacrifices by hanging your head and apologizing for yourself all the time. Humility has its place. But I'd rather make my mistakes by being "insistent," even if it kept me off the debate team and in some people's dog houses now and then.

My grandson inherited his own streak of stubbornness. "Der Apfel faellt nicht weit vom Baum," my mother always said. ("The apple doesn't fall far from the tree.") I wonder if Fred will ever forgive me for tearing down that picture? Maybe he's just coming over here as an excuse to find out whether I still have that picture and will give it back. . . .

You can never tell why some young people are rebellious and others are obedient. Some of the young fellows in my home church changed overnight. Once they were rebels--smoke and drank and had horse races Sunday afternoons. Then they got converted at revival meetings, and all of a sudden they became reactionary and narrow minded. Some of these were the most critical of Bethel College or of any new idea of any kind.

I was just the opposite. I started out conservative and gradually turned liberal. There was a time I was more religious than my parents. I remember one Sunday evening when my father wanted to load some hogs so they'd be ready to haul early Monday morning. I refused to help because Christians weren't supposed to work on Sunday. "What's so sacred about one day in the week?" my father said."You get out here and load hogs!" "I'm not coming," I said. "The Bible says to work on six days and to rest on the seventh." "Then tell your mother to come and help," he said. "And tell her she has raised a son who is some kind of Pharisee. So my mother had to help my father load the hogs on Sunday evening. She was a hard worker--in the house as well as in the field. I felt bad about making her work that time, but I believed there was an important principle at stake.

I even had scruples against the parties and dances the young people in our church had on Sunday evenings. It didn't make any difference to me that the preacher approved of these gatherings--even arranged for them sometimes. Often I just didn't go. When I was teaching public school--after my first two years at Bethel College--I would warn students against worldliness, against the theory of evolution, and things like that. I had my conservative ideals. I was an earnest young man.

I changed from my conservatism very gradually, over many years, even decades. One important event in my senior year at college was the so-called "Daniel explosion"--an open dispute between two of the faculty members. J. F. Balzer, the liberal, had been to the University of Chicago. He was a very good teacher. One day in chapel he spoke about Daniel of the Old Testament. He said the book was written at the time of the Maccabees and that much of it was to be understood symbolically, not literally. The men were not put into a literal fire--that was rather a symbol for surviving persecution.

The very next day a conservative prof, Gustav Enss, led chapel. He attacked Balzer and said it was terrible that we had modernism at Bethel College. The book of Daniel was written just when it said itwas. If it said Daniel was in the lion's den, and if it said an angel held the lion's mouth shut, that's literally what happened.

Well, that caused a big scandal, an open conflict like that. By then I wanted to be a progressive so I took Balzer's side. And I really got upset afterwards when the college board of directors went on an anti-modernist campaign. They called in the teachers and grilled them: "Do you believe in the virgin birth? Do you believe in evolution? Do you believe in the inerrancy of the Scriptures?" Those board members hadn't even heard of the word "inerrancy" before the fundamentalists came along and made it more important than the gospel itself. Even when the teachers passed the test, they protested against such mistrust and such medieval methods. Bethel lost some of its best faculty. For years after that we didn't have much of a real program in Bible. Balzer and Ennsboth left. The fight between the so-called modernists and fundamentalists almost tore Bethel College apart.

After college I married Hazel Dester and we went to China as missionaries. Now here's something else that young people today have trouble understanding. Overseas missions. They think the missionaries are the conservatives. Back in my day the missionaries were the progressives. They wanted to get out and do great things to change the world. Overseas missions seemed like the most dangerous and exciting thing to do. I went to China because that was the frontier of progressive change.

Actually, I planned to go to China from the time I was ten years old. One day I was on the old two-wheeled sulky plow, about a quarter mile from home, plowing with six large horses. A thunderstorm started coming up and began to worry me. I didn't want to rush home if there was no storm. That would be embarrassing. But the thunder and lightening got closer so I pulled the plow out of the ground and headed the horses toward home--out across the bumpy pasture.

It started to rain in huge drops. The lightening flashed and thunder roared like the voice of Jehovah himself. The horses panicked and began to run. I pulled like crazy to hold them back, but they galloped out of control. That plow bounced me way up and down and I thought I was going to die. I prayed to God. "God, get me out of this. Save me. If you help me this time I'll do anything. I'll go to China, God! I will! I'll be a missionary in China!" So I got home safe, even though it rained terribly before we got there.

To this day I can take you to that pasture and show you where I made that promise. God did His part, so I should do mine. After that the direction was set. I was going to China.

[EG looks at wrist watch.] I'm going to get a cup of coffee now. Fred won't be here for a while yet. You might want to stand and stretch. I'm glad you showed up. This reminiscing helps me get ready for the interview.

- End of Part I –

LIVING CREATIVELY, PART II

[EG returns with cup of coffee in hand.]

Let's see, we were on our way to China. . . .

One of my students once asked me, "Dr. Kauffman, do you think people who haven't heard about Jesus are going to hell?" "What happens in the hereafter is God's business, not mine," I told him. "But I doubt if a loving God would do something as unfair as that."

"If you don't think they are going to hell, then what is the point of missions? Why did you go to China?" The student thought he was smart--like he had stumped me.

I told him. "If God gives you some light, you ought to share it! What do you think? People who know something should put their light under a bushel?"

I said before that the early missionaries were the progressives. In fact, we Mennonites had a struggle in the mission field just like we did at Bethel College. Liberals verses conservatives. The liberals were identified with the college and with our Mennonite General Conference. The conservatives were suspicious of the college andconference. Some opposed missions in general. But others supported the so-called independent "faith missions."

My grandfather Schrag was a conservative. Before I left for China he paid me a visit. "I'll give you a quarter section of land to use for the China mission," he said. "But on one condition. You go under a nondenominational mission rather than under the General Conference mission board. I believe in 'faith missions.' You think it over.

Well, now. That was a pretty good offer. A quarter section is 160 acres, eight or nine thousand dollars after it is sold. One could do something on the mission field with that much money. But I didn't like being pushed around with money. And I didn't like grandfather's implication that our conference missionaries didn't go in "faith." I figured it would take just as much faith to go to China without his nine thousand dollars in my pocket.

I was polite with my grandfather. "Thanks for your offer," I said. "But I already promised our conference board we would go with them." "Well," he said. "Then I can't give you the whole quarter. But I'll give you half of it--eighty acres. See that you make good use of it in China." He gave the other half to a distant relative, Jonathan Schrag of South Dakota, who was in an independent outfit called the "Bartel mission." I used my share to build a school in Kai Chow. I wasn't upset with my grandfather. That kind of generous giving made the world-wide missionary movement possible.

Our mission in China was along the Yellow River, the Hwang Ho, cradle of ancient Chinese civilization. Here, I have a map of it. [EG unfolds a map of the mission, hangs it from the hall tree.] We were in the southern neck of Chihli Province, with the river cutting northeast through our field. To get to this area we had to cross the ocean by ship, go overland by train to within thirty miles, travel one day by wheelbarrow, and cover the last stretch in a cart pulled by mules.

Once we got there the first task was to learn the language. Chinese is so different from English. We spent almost a year and a half just studying Chinese--a lot of that out in a village where no one else spoke English or German. The Chinese language has tones that we Americans don't know. The same word has different meanings depending on the tone. Take the word "may." In Chinese it can be may [high tone], may [upward tone], may [downward tone], or may [sliding down and up tone]. One means beautiful; one means coal; one means ink; and one means . . . I forget now what it means. Once I tried to persuade a fellow-teacher to bring some ink tomorrow. He said we didn't need any. But I insisted and said I'd pay him later. Finally he shook his head and went. When he came back we had some coal. Ihad used the wrong tone.

You also have to learn a whole set of new gestures and body language. How do you show the numbers from six to ten? [Encouraging the audience.] Do it with me.

First "Six." We Americans show six with five fingers on the right hand and one on the left. The Chinese do it like this. [Right first with thumb pointed outward.] Now you do it. How much is half a dozen? Six. Come on. Some of you aren't doing it. You'll never learn Chinese if you don't try it.

"Seven" is like this. [Fist with crooked little finger extended.]

"Eight" is like this. [Thumb and index finger out, like pointinga gun.]

"Nine" is this. [Fist with crooked index finger extended.]

You don't need both hands until you get to ten. "Ten" is crossed index fingers, like this.

Let's go back over it: six, seven, eight, nine, ten. Now you know some Chinese gestures. Remember, if you hold up ten fingers like this to show ten, they won't have the slightest idea what you mean. They might even think you mean, "Get away; I don't like you!"

My main job on the mission field was to head the school at Kai Chow, first the grade school and then the high school. We also helped start district schools in outlying villages when the Chinese wanted them. Before we got through we had some thirty district schools. We got a special award from the Chinese government for excellent work in education. I think I have that medal here somewhere. [He begins to rummage for it.] Oh, that's right. I gave it to the Kauffman museum. You can see it on display there—on the Bethel College campus.

Where did the idea get started that the only point of Christian missions was to save souls from hell? Nonsense! We worked to build up all aspects of personal and social life. We were preaching Christ and we were bringing civilization to China. You can call us overconfident, but not narrowminded. Later on the Communists took credit for a lot of the very same things we were doing.

Take footbinding for example. The Communists agreed with us that footbinding was evil--no matter how traditional it was in that culture. It was oppression of women, pure and simple. The mothers would wrap up the feet of little girls so that the toes curled all the way under. Sometimes the bones would break. We didn't allow footbinding in the Christian church.

Maybe sometimes we were too confrontational--like with the snake god tree. Two miles from our place there was a big tree and a little pond. People would come and worship the god in the tree, put some money there, and take some water home for medicine because the god had blessed it. Well, one of our church members owned the land where the tree and pond were, so we asked him if we could cut it down and use it for lumber for the school we were building. He was reluctant at first but then agreed if we took responsibility. We were young and foolish, but we saw a chance to oppose superstition. So we announced to the whole town that on such and such a day we would cut down the snake god tree. We could have had a riot on our hands. The missionaries had been driven out once before in the Boxer Rebellion. Or if something bad happened in the mission after we cut the tree, everybody would say the snake god had taken revenge. But we went ahead.

On the announced day a large crowd showed up--some of them really upset. First we took out the camera and took a picture of the tree. Then we missionaries took the first cuts, and the Chinese Christians did the rest of the cutting. The tree came crashing down, and nothing bad happened to anybody. When we got home that day the story had gotten there ahead of us. Hazel told me the Chinese women said, "Ah, these foreigners are smart. They brought a little box along and before they started cutting they aimed the box at the hole where the god is. They got the god to jump in the box by magic. We heard it click!" Well, I guess the image of the tree was in the box.

My big crisis in China was smallpox. I was vaccinated for smallpox as a child, and then again before going to China. But it never took. I thought I was immune. I was tough--never got sick. But over there I came down with oriental smallpox--that's worse than our kind. I got awful boils all over my body. My head was so swollen it looked like a pillow. Hazel dabbed olive oil over me to help the pain--used more than a whole gallon. My eyes, feet and hands were swollen. My toenails and fingernails came off like thimbles.

For almost six weeks I went in and out of delirium. On the wall at the foot of my bed was the Scripture verse, "as thy days, so shall thy strength be." At times I could open my eyes and see that verse and know where I was. But then I'd close my eyes and slip back.

I was in touch with the hereafter. I had talks with my dead grandfather and my grandmother and others. I woke up and asked Hazel why in the world Dr. Kaufman and others at Bethel College hadn't taught us how to get in touch with the dead. It was so easy. And then there were all kinds of colorful flowers and beautiful music. At times it was like heaven.

The Chinese expected me to die. Nobody comes back from the oriental smallpox. When I finally recovered they had a resurrection celebration. I had been raised from the dead. Some of the older missionaries figured that this crisis would cure me of my liberal ideas. I guess they were disappointed. But ever afterward I was convinced that God had spared me for some special task.

I was sure that God's task for me would be in China. It would be to educate young people who would lead the way in building a new China--a progressive China infused with Christian values. Two of such young people were my students James Liu and Stephen Wang. I made it possible for them to study at Bluffton and Bethel Colleges in America. They were the first leaders from any Mennonite overseas mission field to come and study in America. What a tragedy it was that World War II and the Communist Revolution kept them from having full and productive careers. Whatever God's plan for China was, it didn't seem to mesh exactly with mine. Of course, the whole story is not yet told.

In 1925 Hazel and I came home for our furlough with a definite plan. I would get a Ph.D. degree and we'd return to teach at a university in China. We'd be able to prepare Chinese Mennonites there for church work. But I got caught in the big modernist-fundamentalist storm of the 1920s, and it kept me from getting back to China. That old "Daniel Explosion" at Bethel was just the first in a whole series of fires that never seemed to go out.

I guess some of the conservatives gave up on me when I went to the University of Chicago. Chicago was a dangerous school because Chicago made it a practice to think. The Chicago profs believed God had made man's mind as well as his body. We should use our minds creatively. Sometimes our mind's discoveries will contradict old doctrines. Long ago people believed that the earth was the center of the universe, that the sun revolved around the earth. And they quoted the Bible on it too. Old orthodoxies die hard.

In Chicago I discovered the idea of human creativity. Cod is the ultimate creator, of course.God created us his own images owe would be creators too. Once you know God's will, once you understand the Bible, then you have a guide for living creatively.

The word went out. "Ed Kaufman is infected by liberalism. Ed Kaufman is a modernist. Ed Kaufman shouldn't be allowed to go back to China. Some people even tried to get the mission board to forbid me to do itinerating among the churches.

The opposers didn't have any evidence against me, and they sometimes grabbed onto some very stupid arguments. In one church in South Dakota, after I finished speaking about China, the preacher got up to contradict me. I had said China was a sleeping giant; she would one day rise to play a major role in civilization. This preacher said, "Kaufman does not understand Biblical prophecy. The Bible says the dark-skinned people of the earth are under the curse of Ham. That includes the Chinese. China will not rise. China is under a curse." Of course that is nonsense. The Bible says no such thing. But that preacher was so afraid of modernism that when he tried to attack it he got into something a whole lot worse.

For my doctoral dissertation at Chicago I wrote about the rise of the Mennonite missionary movement. It was published as a book, with the help of the conference mission board. The fundamentalists tried to find fault with this too. A copy from one of them later came to the Mennonite Library and Archives at Bethel. I have it here. [He gets it from the shelf.] Here's what he wrote on the inside cover:

"Very significant is the fact that a Chicago University man should have a hand in this book. . . . That place is a hotbed of modernism . . . the sinister teaching of the book is cleverly and secretly woven into the whole book, sometimes by a mere word, question mark, sentence or occasional paragraph. . . . It's a shame the mission board ever backed this. A poisonous volume, not fit for Christians who cannot quickly discern modernism." [He slams book shut.]

How do you argue against something like that? The man knew I was a modernist for sure, but I was so clever and secret about it that he couldn't find real evidence of it! It's got to be dangerous. You can't even see it!

The truth is I was a progressive, not a modernist. I believed orthodox Christian teachings, and I accepted the authority of Scripture. I yearned for a chance to meet my accusers and put them down hard. But in my better moments I also knew that a big confrontation wouldn't do any good. I never was brought to a church trial, like happened in some Protestant denominations. Anyhow, I had a lot of support among the more enlightened members of the mission board and in the churches. The times cried out for confident builders, not frightened critics.

Some people say we should forget these old disputes, cover them over and not let the younger generation find out about them. I disagree. Where there is life there is struggle. This generation will have its own battles to fight, and they can do it a lot more intelligently if they know where they have come from. The only problem is if we aren't prepared to tell them.

As it turned out, my chance to build came in America, not in China. Bluffton College in Ohio wanted me. The seminary board needed a president for its new school in Chicago. And then Bethel College, my own alma mater needed a new president. Three times I turned down that job. I wanted to go back to China. I finally gave in after my fellow missionaries, especially P. A. Penner, the senior missionary of our conference, urged me to take the job at Bethel. He said that if the church was to have an ongoing mission it would depend on training Christian workers at places like Bethel College. Today I know he was right. Today it seems more clear, even why I survived smallpox in China. God had work for me at Bethel College.

I'll tell you more about the Bethel story after another short break. After that Fred will soon be here. Don't go very far away.

LIVING CREATIVELY Part III

In 1932 before I took over as president of Bethel College I had a long talk with Henry Peter Krehbiel. He was a newspaper man and a critic of Bethel. "Young man, I can make or break you," he started our conversation. "I broke Kliewer" (the president before me), "I broke Kliewer and I can break you too."

He probably could have. Three years earlier Krehbiel led a movement to reorganize Bethel into a Bible school. They came within eight corporation votes of getting control. Bethel hung in the balance between a broad-minded Christian liberal arts college, and a narrow-minded fundamentalist Bible school.

"Young man, what do you think about lodges and secret societies?" Krehbiel grilled me.

[decisively] "I'm not a member and I don't plan to be one,"I said. "I'm against secrecy. I favor openness."

[HPK] "What's your position on the ecumenical movement?"

[EG] "If we Mennonites have something to teach the other churches, let's teach it to them. But let's keep our own distinctive heritage and tradition."

[HPK] "Do you teach the higher criticism?"

[EG] "I teach the Bible as God's Word. I think we should study the Bible with the best historical and literary tools we have. The more we study the Scriptures, the more their essential truth will be vindicated."

He didn't argue with me. I could tell that he wanted forthright and decisive answers. He wouldn't respect weakness. So I took the argument right to him.

"Mr. Krehbiel, with all we Mennonites agree on, isn't it time for us to start building together rather than tearing each other down?

"We agree on the need for Christian education, don't we?" [EG indicates that HPK approves with nod of head.]

"We agree on the importance of overseasmissions. [agreement]

"We agree on a strong peace witness. [agreement]

"We agree that the church needs strong new leaders. [agreement]

"This is why I asked to see you. I am going to start an aggressive movement to get Bethel College moving again, and I want your support."

Well, Krehbiel wouldn't commit himself at that first meeting. Some time later I gave my first public presidential report on the state of the college at the Alexanderwohl church. When I was done, H. P. Krehbiel stood up to make his comments. He was so famous as college critic that everybody hung on his words. You could have heard a pin drop in that sanctuary. He cleared his throat, paused for effect, and finally said, "After all we've been through, I'm thankful to God that Bethel finally has a president who tells us really where Bethel College is at, where it should be going, and what we have to do to get it there." Well! That was the first turning point in my presidency.

H. P. Krehbiel was on my side. Kliewer later told me, "He's sick and tired of fighting. He wants to get on the water wagon too."

I inherited a financial crisis. Bethel had a hugedebt. Every building and piece of property on the campus was covered with first and second mortgages, and for the last $12,000 borrowed each board member had to sign as personally responsible. The whole country was in a depression in those years. We started a bunch of new programs to restore confidence: Bethel College fellowship groups in the churches; a college farmand dairy to provide work for the students; a reorganized curriculum and school calendar. Later we were able to start a new building program--a Memorial Hall which was the biggest project on campus since the administration building fifty years before. People can see bricks and mortar. We could pay off the debt while doing something new.

One of my programs cost a lot of good will among the faculty. When we were cutting expenses to the bone, we asked the teachers to donate ten percent of their salaries to the school. When they agreed, we just deducted the amount from their monthly payments and gave them tax credit statements as well as votes for college corporation meetings. In those years the corporation gave one vote for each hundred dollars donated.

One teacher asked, "Is this program voluntary?""Everyone is cooperating," I said. "If you don't want to cooperate, I'll start looking for your replacement. This is a matter of Bethel's survival. My salary is being cut in just the same way." Sometimes I heard about faculty dissatisfaction through my own children, Gordon and Karolyn. One time Gordon heard that the monthly teacher checks were being delayed when the account was low. "Don't you have any respect they for your teachers?" Gordon shouted at me. "Don't you care that they have grocery bills to pay? Do you enjoy treating people like dirt? You ought to hear what they're saying about you." Well. I didn't become college president to win a popularity prize. But maybe Gordon helped me get the checks out a little sooner than planned that time.

To build up the college dairy herd we asked farmers to donate cows. Livestock didn't bring too much during the depression anyhow. Of course the donated animals weren't always top quality. I remember one time going over to the barn at milking time and looking up the record where the boys put up how much milk each cow was giving. These fellows had put up names for each cow--but not names like Flossie and Bossie. They chose the names of bosomy Hollywood starlets--Greta Garbo, Mae West, Betty Grable. The boys knew I was looking at those names. They just kept their heads down and milked old Mae West and the others like nobody's business. Nobody said a word. I guess they had the same thing on their minds as my grandson Fred with his picture. Maybe college students don't change much from one generation to the next.

This little Bethel College bank was an idea a lot of people liked. It's a replica of the administration building. Get our people to drop coins into here, and it's like investing in Bethel. [He shakes the bank.] Listen to that noise; it must be a good start for the "on to Bethel" Club. I wanted to have little children all over North America shaking these little banks.

Some of the new ideas I brought along from the University ofChicago--like the quarter system for our college calendar. Other ideas I got from a summer seminar for young college presidents which I attended that first year. We got the jump on other colleges in the state in more than one way. For example, we were the first school in Kansas to offer the graduate record examinations.

The big goal for Bethel was to get accredited by the North Central Association. None of the Mennonite colleges were accredited at that time, and it took us five applications to get the job done. We practically memorized those North Central books. There were seventy-two different measurements we had to meet for accreditation. We had to build up endowment, improve faculty, develop the plant--everything. I sent five senior faculty back to university to get Ph.D. degrees. We started the Mennonite Library and Archives to be a strong research center. We got Charles Kauffman to bring his natural history museum from South Dakota to Bethel. We raised endowment money.

I sent a telegram home from the meeting in Chicago when we finally got accredited. When I got off the train at Newton, the students were at the station to meet me. They hoisted me up on their shoulders and carried me a block or two into town toward campus. They were shouting and singing, "Maroon and Gray oh fairest colors, hail to thee we e'er shall sing." It was some celebration.

In those days the president of the college taught classes. My most important course was called "Basic Christian Convictions," something all seniors had to take before graduation. The capstone of the course for each student was a personal "credo," a statement of their own religious beliefs. The challenge was to teach young people to think--not what to think, but to think. What a joy it was to see the formation of mature Christian conviction. As long as they were honest and vigorous seekers, I never worried about them. Education is creation, not indoctrination.

Every era has its challenges. We had barely gotten out of the depression when World War II hit us. War is always tough for pacifists, especially if they have a German accent and the war is against Germany. When the war started in '41, a Rotary committee from town came in to talk with me--a couple of lawyers and others. They said, "Now look here. You've been around the world and know how things are. The Mennonites are isolated, still in the woods, and we don't expect them to understand why America has to fight its enemies. But we don't think you'll let the conscientious objector business keep you from supporting America. Why don't you come down off the fence?"

It was time to speak plainly. "I want to thank you men for coming to see me about this. I respect your views. Bethel needs your friendship and support. But if you think I'm on the fence, there's only one side for me to get off. That's on the Mennonite side, with my religious heritage." They just couldn't understand how an intelligent and decent man wouldn't fight for his country. I stayed in Rotary, but the war drove a wedge between us.

Things really got hot after one of our good students, a fellow named Lawrence Templin, wrote an article in the college paper favoring non-registration for the draft. The faculty advisor should have stopped the article, but it got printed for some reason. Then the threats started coming, some in anonymous telephone calls, some in the mail.

"Get rid of that student or we'll come out with tar and feathers."

"Straighten out or you'll never get support from Newton again."

"Let Bethel College declare itself!"

I had Lawrence move out of the dormitory and stay at my house several nights for his own safety. The faculty and administration put out statements saying that anti-registration was not the college position. We posted all night guards to discourage the rabble-rousers from doing something drastic. Gradually the thing blew over.

The war experience was tough, but it also showed what kind of stuff we were made of. There were new chances for service. I was proud of the way our Bethel College graduates took leadership in the Civilian Public Service camps. Mennonites always have a special mission in wartime.

Where would mankind be today without the creative, independent, and crusading thinkers? Somebody must dare to dream of a world without war, and pay the price of living that way. Somebody must dare to dream courageously of a society which will guarantee to all people greater opportunity for education and employment. Somebody must dare to dream that Jesus' kingdom can transform the world we live in.

That's what Christian mission and Christian education is for. That's what I gave my life to.

[Doorbell rings.]

There it is. That's Fred. You say a prayer for me as I talk to my grandson. And for yourself when your opportunity comes to pass on the faith to your next generation. Goodbye.

- THE END -

Some discussion questions to follow "Living Creatively":

- Do you remember E. G. Kaufman? What memories do you have of his work, his teaching, or his preaching?

- How do you pass on values to the next generation?

- Was the fundamentalist-modernist conflict a serious one? Was Kaufman biased in his reporting of the issues? Have those conflicts been resolved?

- Was Kaufman right that the liberals and the conservatives had more agreements than disagreements?

- Do you think Kaufman did the right thing in tearing down his grandson's picture? Was he perhaps sorry he did it?

- What is your image of overseas missionaries? Progressive or conservative? Broad-minded or narrow-minded?

- How do you assess Kaufman's aggressive style of leadership? Would it be successful today?

- Do you agree that the next generation should hear about all the conflicts of this generation? Shouldn't some things be forgotten?

- Kaufman claimed he gradually changed from conservative to liberal. Was he correct in this self-assessment? Do most people do this, or do most become more conservative?

- Do you think Kaufman will be successful in communicating what he wants to get across to his grandson?