In the spring of 1942, not long after my fourth birthday, I saw my grandpa sitting on the weathered board base of the old Woodmanse steel windmill on the Juhnke farmyard.

I went over and sat beside Grandpa, resting my elbows on my knees like he did. He was chewing on a stem of green grass. We sat silent, facing southward, looking across the yard toward the flowering mulberry tree that stood between the farm house and the chicken shed. The windmill wheel with its curved galvanized blades was barely creaking some twenty-five feet above us. The stock tank was full and Grandpa had turned the hand crank chain to draw the wind vane against the wind wheel so it would stop pumping water.

I wanted a stem of grass to chew on like Grandpa did. Nearby was some grass growing in the wet soil where water fell from the windmill pump spout leading into the pipe that fed the stock tank. I pulled at the grass.

Grandpa looked at me, grinned, and asked, “Are you a little Dutchman?” Then he laughed.

I was stumped. I didn’t have the slightest idea what a “Dutchman” was. Nor did I know why Grandpa laughed. I couldn’t think of anything to say. So I just sat there and looked down in embarrassment.

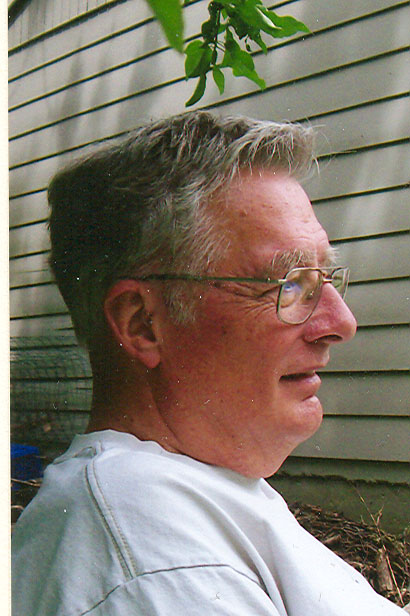

What could I have said? Perhaps I should have asked, “Grandpa, what is a Dutchman?” But I didn’t know how to have a conversation with Grandpa. We never talked. Nor did he play with me. Grandpa was the silent type--an austere, hard-working, sun-burned Mennonite farmer who wasn’t given to warmth in personal relationships of any kind. Maybe he would have answered, “A Dutchman is a German.” He wouldn’t have gone on to explain that “Dutch” means“Deutsch,”and that “Deutsch”translated into English means German.

If I had been really bold, I might have asked, “Grandpa areyoua Dutchman?” To that question he might have responded, “Ja,” without bothering to elaborate. And he would have laughed again.

Unlike me, Grandpa Ernest Juhnke had notlearned to name his identity from his grandfather.All four of his grandparents had died in the OldCountry before the great migration of the 1870s.Grandpa’s orphaned immigrant parents, CarlFriedrich Wilhelm Juhnke and Frances Kaufman,had homesteaded in northern Nebraska. They hadhad four children in Nebraska, and then had movedto south-central Kansas where they had three more.

Everywhere the Juhnkes lived, they were part of aGerman-speaking, pork-potatoes-and-kraut-eatingimmigrant community. They were Germans in America.And that, I suppose, is why Grandpa laughed at his own question. Living on the boundary of alternative ethnic identities always produces humorous ironies. German words and English words get scrambled in funny ways. Language getsupgemixed. New American foods are put on the table in strange combinations with traditional German ethnic foods. Fruit jello is served alongsidekäse peroggi.German-American newspapers juxtapose Abraham Lincoln and Otto von Bismarck as political heroes. No wonder that a grandpa looks at his grandson and imagines how the next generation will put together their Germanism and Americanism.

Perhaps Grandpa laughed because he lived on another boundary that his grandchild would have to negotiate. He was a Dutchman who had married aSchweizer. Grandma Alvina was a Swiss—actually a “Swiss-Volhynian.” Before they immigrated to America, the Swiss-Volhynian Mennonites had moved from Switzerland via the Palatinate to central Europe on paths several hundred miles to the south of the Juhnke homeland in Farther Pomerania. The Swiss-Volhynians spoke their own German dialect that was barely understandable to the Juhnke Dutchmen. The Juhnkes had picked up a kind of low German dialect on their wanderings from the Netherlands to Farther Pomerania. When the Juhnkes married into the transplanted Swiss-Volhynian Mennonite community in America, they had to adapt toSchweizerways of talking, eating and behaving. Ernest Juhnke was culturally co-opted by the MennoniteSchweizers, but he never forgot that he was at heart a Dutchman. And he took delight in the thought that his grandson might beat the odds and turn out in some ways to be a Dutchman too—if also partlySchweizerand partly American.

Today I am a grandfather myself. I have spent a career teaching American history. I now wonder if Grandpa’s question to me in the spring of 1942 had anything to do with the fact that the United States and Germany were at war. German identity in 1942 was a badge of shame. German-Americans were trying to hide their national/ethnic identity, not to make it known. Was Grandpa’s laughter a little nervous, given the patriotic American anti-Germanism that was so strong in Kansas?

Probably not. More likely, Grandpa’s question and his laughter were celebrative. What he really meant was, “Grandson, are you going to be like me?” He laughed because he instinctively understood that I both would--and would not--be like him. He laughed out of delight that his own life and contradictory identities would somehow live on into the coming generations.

Never underestimate the power of a timely, well-stated question. Under the windmill in 1942 Grandpa asked if I was a little Dutchman. At age twenty, in 1958, I went to Germany in part to look for an answer to that question. In the next generation, my two children studied in Germany. Even today, at age seventy-two, I feel the tug of Grandpa’s question whenever I chew on a stem of green grass.