Reprinted from Mennonite Quarterly Review 93, no. 3 (2019): 428-31.

As its prefatory “Note on the Novel” states, Miriam Toews’s Women Talking is inspired by the rapes that occurred “Between 2005 and 2009” in a Bolivian Mennonite colony and then resumed in 2013 even though the original perpetrators were imprisoned. The book takes place in June 2009 as women from two families who have been chosen as representatives for all of the colony’s women discuss whether or not they should all leave the colony as a response to the violence against them. The decision must be made quickly so that if they choose to go they can do so while the men are in “the city” trying to get the rapists released on bail (5). The novel consists of the minutes from the women’s deliberations broken up into five chronological chapters which span the two days of the meeting.

The minutes are being taken by a man, August Epp, because the colony does not teach its women to read or write. Toews takes some poetic license here as, according to the Mennonite Encyclopedia, Bolivian Old Colony Mennonites educate girls through “the age of 12.”[1]August is an outcast because he is single, because he is bad at farming, and because his parents were shunned when he was a child so he has just recently been allowed to return to the colony. He has also served prison time for stealing a horse that a cop was mistreating at a protest (143). The colony’s men hate him, which is why the women trust him not to tell the men about their conversation. Although the women will be unable to read the minutes, they want them taken so they can be “an artifact for others to discover” (51). The women recognize the importance of witnessing to their experience; they recognize that their voices are valuable even though the men teach them otherwise. Similarly, Women Talking itself acts as a witness for the real-life women who were attacked. Therefore, whether the women’s illiteracy in the novel is factually accurate or not is immaterial because its function is to symbolize the gender-based oppression both they and their real-life counterparts endure.

The novel begins with three illustrations (clouds over a field, a Mennonite woman and man facing off in a knife fight [!], and a horse’s behind; see Figure 1) that correspond to the women’s three possibilities: “1. Do Nothing. 2. Stay and Fight. 3. Leave” (6).

Due to their lack of education the women know that “The only certainty [they]’ll know is uncertainty” if they leave because they do not know where it is possible for them to go (53), but the alternative is that they will have to forgive the rapists or be excommunicated if they refuse. I will refrain from discussing the plot further so as not to spoil its conclusion, which, to Toews’s credit, is suspenseful and satisfying even though readers know from the very beginning what its small list of possible outcomes encompasses. The eight women in the conversation each become vivid as individual characters through their words.

Toews is the premier Mennonite writer working today, and Women Talking solidifies this status. Its nomination for the 2018 Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction, Canada’s highest literary prize (it lost to Sarah Henstra’s The Red Word), shows that it is an important literary accomplishment, period, not only an important Mennonite literary accomplishment. It is an aesthetically beautiful book that treats its difficult subject matter (and it is difficult, especially the first half, to the point where there were times when I wondered whether I would be able to finish it) with grace and kindness. While it is similar to Toews’s other Mennonite-related books (Swing Low, A Complicated Kindness, Irma Voth, and All My Puny Sorrows) in that it includes subjects such as suicide, the search for selfhood, and humor-infused anger about Mennonite repressiveness, it explores them in non-repetitive ways. It is an instant classic. Anyone interested in Mennonite thought should read it, scholars and laypeople alike.

But Women Talking is even more significant for its argument about the current state of Mennonitism in the Americas than for its aesthetic accomplishments. Despite its Governor General’s loss it is Toews’s most important book, surpassing her 2004 winner A Complicated Kindness because of how, even though it is fiction, it is also a theological statement about Mennonites’ continued hypocrisy regarding pacifism, as we claim that war is wrong while we continue to tolerate domestic violence against spouses and children. In the novel, many of the rapists are family members of the women, and aside from the rapes themselves, there are numerous stories of men abusing women physically and psychologically. Mennonite literature has a long history of examining this issue, with writers such as Di Brandt and Patrick Friesen documenting it in their work from the 1980s. It is incredibly damning of the Mennonite community that instances of it are still available for Toews to write about. While the book takes place in Bolivia, and thus it might be tempting for North American readers to dissociate ourselves from the troubles there, the same misogynist spirit that led to the rapes is present in actions such as some Mennonite theologians’ continued insistence on using John Howard Yoder in their work despite his extensively documented history of sexual predation. In other words, Toews’s novel implicates all of us Mennonite men in this hemisphere. Rather than being concerned about the issue of writing about a Mennonite group that she is not a part of, Toews’s choice to do so claims that all of us who use the term “Mennonite” to identify ourselves in some way have an obligation to be concerned with each other. The novel thus acts as a call for unity as we work to eradicate the violence in our Mennonite community.

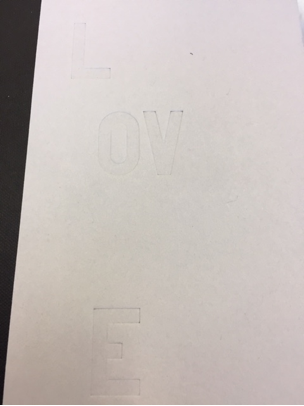

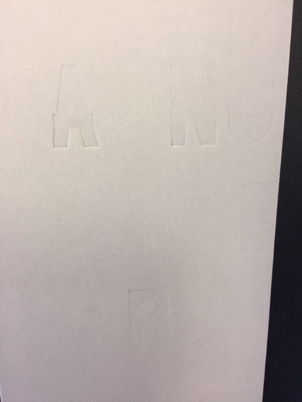

The book has the word “LOVE” embossed in the cardboard of its front cover and the word “ANGER” on its back cover, features that are easy to miss because it is necessary to remove the dust jacket to see them (see Figures 2 and 3).

These words represent Women Talking’s message to the Mennonite community. It is a critique written with the hope that the community will get better rather than an outright rejection of it, simultaneously angry and loving. Ultimately, like the women, it affirms Mennonite ideals of “pacifism, love and forgiveness” (111), arguing that the possibility of change in the community exists. Women Talking is a polemical book--and thus this review may be more polemical thanMQR’s reviews usually are--and it is a necessary one. We would all do well to heed the lessons it teaches.

[1] Gerald Mumaw, “Bolivia,” in The Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, June 2013, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Bolivia#2013_Update, accessed 20 December 2018.

Daniel Shank Cruz (they/multitudes) is a genderqueer bisexual disabled boricua who grew up in the Bronx and Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Multitudes is the author of a book of literary criticism, Queering Mennonite Literature: Archives, Activism, and the Search for Community (Penn State University Press, 2019), and a hybrid memoir/literary critical text, Ethics for Apocalyptic Times: Theapoetics, Autotheory, and Mennonite Literature (Penn State University Press, 2024). With James Knippen, they are the co-author of It Breaks Your Heart: Haiku and Senryu on the 2023 New York Mets (Redheaded Press, 2024). Their writing has also appeared in venues such as Acorn, Blithe Spirit, Failed Haiku, Frogpond, Kingfisher, Modern Haiku, Religion & Literature, Rhubarb, and numerous essay collections. Multitudes also maintains the three Mennonite/s Writing Bibliographies at mennonitebibs.wordpress.com. Visit them at danielshankcruz.com.

Daniel Shank Cruz (they/multitudes) is a genderqueer bisexual disabled boricua who grew up in the Bronx and Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Multitudes is the author of a book of literary criticism, Queering Mennonite Literature: Archives, Activism, and the Search for Community (Penn State University Press, 2019), and a hybrid memoir/literary critical text, Ethics for Apocalyptic Times: Theapoetics, Autotheory, and Mennonite Literature (Penn State University Press, 2024). With James Knippen, they are the co-author of It Breaks Your Heart: Haiku and Senryu on the 2023 New York Mets (Redheaded Press, 2024). Their writing has also appeared in venues such as Acorn, Blithe Spirit, Failed Haiku, Frogpond, Kingfisher, Modern Haiku, Religion & Literature, Rhubarb, and numerous essay collections. Multitudes also maintains the three Mennonite/s Writing Bibliographies at mennonitebibs.wordpress.com. Visit them at danielshankcruz.com.