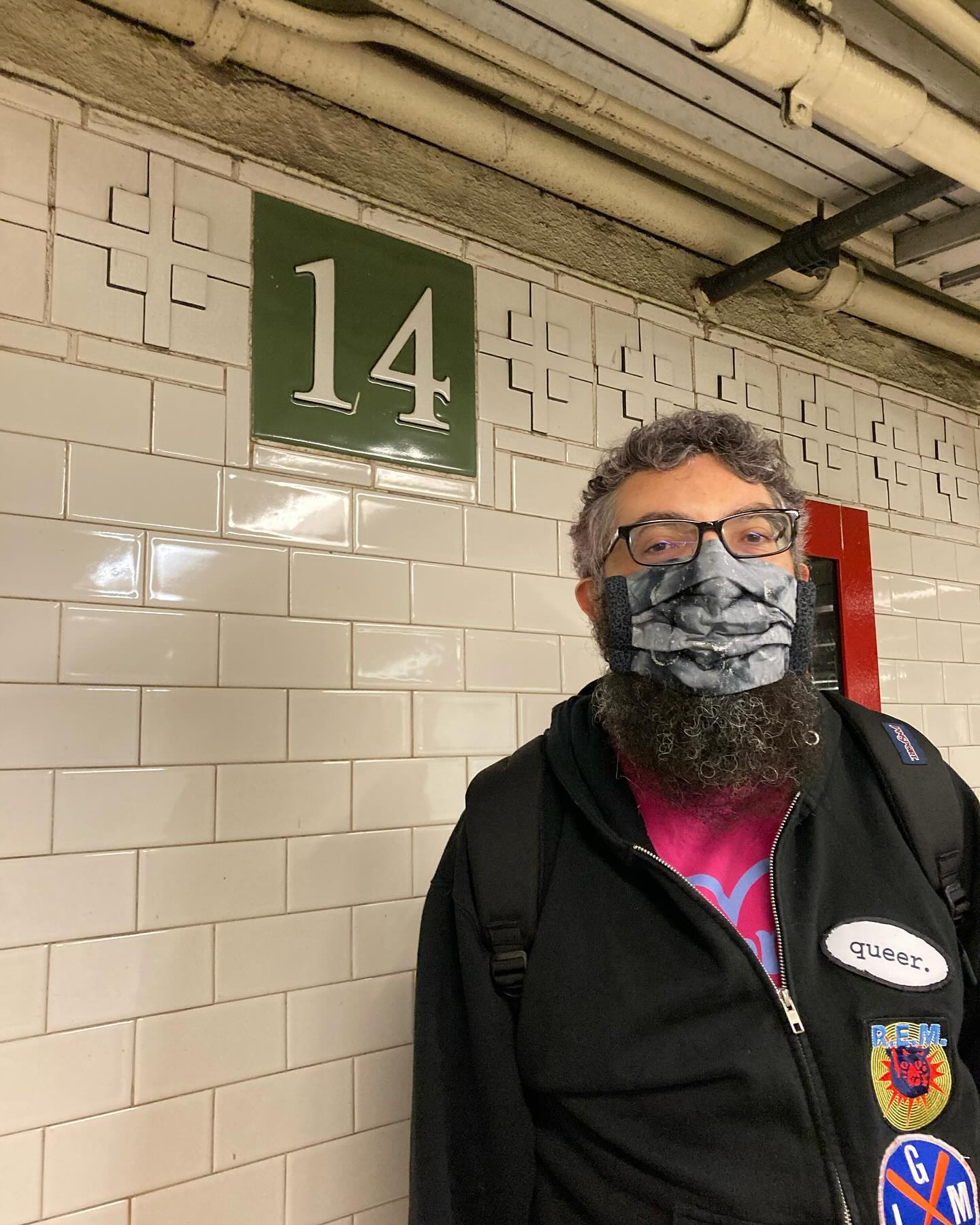

As soon as I walked out of the tattoo parlor on 10 July 2018 I posted the above photograph on Facebook (i.e., documenting my documenting, and when this essay goes online I will share the link on Facebook, continuing the documentation spiral) along with the caption "New tattoo! I've been thinking about getting one for a while, and living under a government that wants to silence me as a queer person of color made me decide to get a design that makes both of those parts of myself explicitly visible."[1]

The tattoo resulted from an experience earlier in the summer. In mid-June 2018 I went on a Mennonite Central Committee-sponsored Arts Learning Tour to the Arizona-Sonora border. When I got home, I could not stop thinking about it: the trip infused my dreams almost every night and made it hard to concentrate on tasks during the day. I felt displaced; I felt helpless about being so far away from the border where bodies are needed for the resistance; and I missed the community of fringe Mennonite artists that the tour created. I needed a way to document my feelings, and since traditional writing was not working, I decided to get the tattoo.[2] This felt like an appropriate genre because of its visibility and, frankly, because of the pain it entails. I wanted a way to feel the turmoil going on in my head in my flesh as well.

Although the MCC tour focused on the U.S.-Mexico border, more broadly it raised questions about the place of Latinxs in U.S. society.[3] My Latinx identity does not require me to consider issues of "illegal" immigration because Puerto Ricans currently have U.S. citizenship. However, when one of the activists who spoke with the group, Maria Padilla, called the U.S. government's border policies "ethnic cleansing," I knew her term also applies to the slow death being perpetrated on Puerto Rico by the current administration's continued refusal to repair basic utilities or offer other substantial forms of aid after Hurricane Maria. Thinking about these two sites of violence, I wanted to symbolically put my body on the line as a form of protest because I could not (and cannot currently) be in either place.

Each element of the tattoo signifies radicalism. As queer theory teaches, queerness is a political stance, not just a sexual preference. Consequently, I chose the word "queer" rather than "bisexual." I chose the flag to represent my Puerto Rican identity because of the flag's history as an anti-imperialist symbol. After it was designed in 1895, the flag was illegal during the last few years of Spanish rule and remained illegal under U.S. rule until the mid-twentieth century. "Boricua," the Taíno word for a Puerto Rican,[4] also has anti-imperialist implications. Thus, the word does more than simply differentiate the uncolored flag from Cuba's. By combining these three elements, the tattoo archives resistance, political solidarity, sex, and hope as a joyful marker of parts of my identity.

Of course, the tattoo's design misses a third major part of my identity, my Mennonitism.[5] One might argue that the plain aesthetic which preferred an outline of the flag to a color version of it is a result of my Mennonite upbringing, but it is fair to ask why I did not choose a design that made this element of my identity more visible. One practical reason is that I am not sure what an explicitly Mennonite tattoo would look like. Would it be a portrait of Menno Simons? Goshen College's motto "Culture for Service"? Something from the Martyrs Mirror?[6] Perhaps the unintelligibility of the Mennonite in the tattoo genre indicates something about the worldliness of marking the body.

However, the more important reason that the tattoo is not explicitly Mennonite is that I do not feel persecuted as a Mennonite,[7] and I wanted a design that openly celebrates membership in groups that the current government wants eliminated. Now anytime I wear short sleeves my body is a testimony that resistance exists and will not be quieted. As Mennonites well know, sometimes one consequence of testimony is violence. My tattoo's visibility may also work in negative ways. If the current administration starts systematically hunting down U.S. citizens whom it deems objectionable in the way it currently hunts immigrants, I will be easy to find. Getting my tattoo in the current political climate is a little like a sixteenth-century Anabaptist getting a tattoo that reads "ask me about my second baptism" or "infant baptism is for sinners," so maybe there is a hint of problematic self-martyring going on, in which case the tattoo is super Mennonite!

Joking aside, one unexpected happy consequence of the tattoo is that I see my body differently now. The design challenges me to live up to the ideals that it represents, so emotionally I feel bolder, and I also love looking at it, which, in combination with the necessity of several weeks of aftercare, has caused me to pay much more appreciative attention to my body than I usually do. I still struggle mightily to unlearn the negative attitudes toward the body that the church gave me (e.g., although it is illogical I still cannot bring myself to join a gym or engage in any kind of regular exercise routine because it feels too prideful), but the tattoo has been a good reminder to enjoy my body and to think of it as an active work in progress. As part of this enjoyment, three weeks after getting the tattoo I got a second one, inscribing the last three lines from the 1855 version of Walt Whitman's Song of Myselfonto my other arm as a reminder to celebrate the body as exuberantly as the poem does.

[1] https://www.facebook.com/danielshankcruz/posts/10155259698916627.

[2] It is a happy turn of events that the tattoo has led to this essay.

[3] This is in part because, of course, Mexicans are not the only ones who attempt to cross this border in what the U.S. government considers "illegal" ways. People from other Central American countries, most notably Guatemala, often attempt to cross, and, as we learned on the tour, it is not uncommon for Europeans to fly to Central or South America and then attempt to cross into the U.S. on foot, some walking from as far away as Brazil.

[4] It now often connotates someone with Puerto Rican heritage living in the U.S.

[5] See Daniel Shank Cruz, "On Postcolonial Mennonite Writing: Theorizing a Queer Latinx Mennonite Life," Journal of Mennonite Writing 9, no. 4 (2017): https://mennonitewriting.org/journal/9/4/postcolonial-mennonite-writing-theorizing-queer-la/?page=5#all, which discusses my attempts to integrate all three of these identities.

[6] At least one person, Benjamin L. Corey, has a Dirk Willems tattoo. See https://twitter.com/BenjaminLCorey/status/714817081192161281. My thanks to Julia Spicher Kasdorf for bringing Corey's tattoo to my attention.

[7] Unfortunately, though, the two identities included in the tattoo are persecuted by institutional Mennonitism to various extents; the tattoo is a statement of defiance in both secular and Mennonite contexts.

Daniel Shank Cruz (they/multitudes) is a genderqueer bisexual disabled boricua who grew up in the Bronx and Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Multitudes is the author of a book of literary criticism, Queering Mennonite Literature: Archives, Activism, and the Search for Community (Penn State University Press, 2019), and a hybrid memoir/literary critical text, Ethics for Apocalyptic Times: Theapoetics, Autotheory, and Mennonite Literature (Penn State University Press, 2024). With James Knippen, they are the co-author of It Breaks Your Heart: Haiku and Senryu on the 2023 New York Mets (Redheaded Press, 2024). Their writing has also appeared in venues such as Acorn, Blithe Spirit, Failed Haiku, Frogpond, Kingfisher, Modern Haiku, Religion & Literature, Rhubarb, and numerous essay collections. Multitudes also maintains the three Mennonite/s Writing Bibliographies at mennonitebibs.wordpress.com. Visit them at danielshankcruz.com.

Daniel Shank Cruz (they/multitudes) is a genderqueer bisexual disabled boricua who grew up in the Bronx and Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Multitudes is the author of a book of literary criticism, Queering Mennonite Literature: Archives, Activism, and the Search for Community (Penn State University Press, 2019), and a hybrid memoir/literary critical text, Ethics for Apocalyptic Times: Theapoetics, Autotheory, and Mennonite Literature (Penn State University Press, 2024). With James Knippen, they are the co-author of It Breaks Your Heart: Haiku and Senryu on the 2023 New York Mets (Redheaded Press, 2024). Their writing has also appeared in venues such as Acorn, Blithe Spirit, Failed Haiku, Frogpond, Kingfisher, Modern Haiku, Religion & Literature, Rhubarb, and numerous essay collections. Multitudes also maintains the three Mennonite/s Writing Bibliographies at mennonitebibs.wordpress.com. Visit them at danielshankcruz.com.