The cottage where Gonzalo was recuperating was one of eight identical cottages between an abandoned business and an alley that ran south toward Mexico. Gonzalo's right foot was gone; how exactly, he couldn't remember. Philip, the strange little man who had nursed him back to health, had found him bleeding on the street in downtown San Diego, unconscious. There'd been an explosion, and only Gonzalo's fire retardant properties had saved him from major skin burns, Philip said. Philip was growing him a replacement foot, but it wasn't ready yet, and Gonzalo was still ill.

He was often feverish. He would dream only about the most horrible things. He dreamed of a cyborg woman with fiery hair running on two bloody stumps away from the airport, down straight empty roads into the city. He dreamed of prison guards peeing through holes in the fence around a construction site, where some enormous consciousness was being built that would feed on human pain. He dreamed that he was wandering through a world in which humanoid creatures no longer felt anything except a vague desire to be looked at. In the dream, he was trying to find a boy or a girl. He was trying to find a garbage dump. He was trying to find human emotion. He needed to feel alive.

One afternoon he woke to see Philip closely examining the wires emerging from his stump.

You've acquired a computer virus in your cyborg mechanism, Philip told him. It's quite something.

It was as if these words were coming from a great distance, and Gonzalo thought that if he could make it to that place the words came from, far far away, then he would finally weep.

If you can't get rid of it, just take out the machine parts, said Gonzalo. I'll be human again.

No, he won't let me. He told me so.

He?

At first I thought he was bluffing, Philip said. But no. He could inflict some serious damage on your biological parts if he wanted to.

He?

He identifies male, not sure why. His name is Eeshoo.

It seemed to Gonzalo that he was trapped inside a dream, while out there in reality somewhere, Philip communicated with invisible forces. Philip received all kinds of messages. It was some sort of message from the underground that had led him to Gonzalo's body in the first place. He spent much of his time printing up a variety of texts on actual paper--news stories, science articles, poems--and cutting them into pieces, along with scraps of paper he found on the street, flyers, advertisements, the scrawled magical rantings of schizophrenics, messages that never arrived at their intended destinations. He recombined the fragments, and claimed that in this way he received communications from the future and from the past, although he couldn't always distinguish which was which. He was also a scholar of sorts, whose specialty was the history of alien abduction narratives from the 1960s to the present day.

Eeshoo's been helping me with some of the technical issues of constructing your foot, Philip told him. George has been helping me with others.

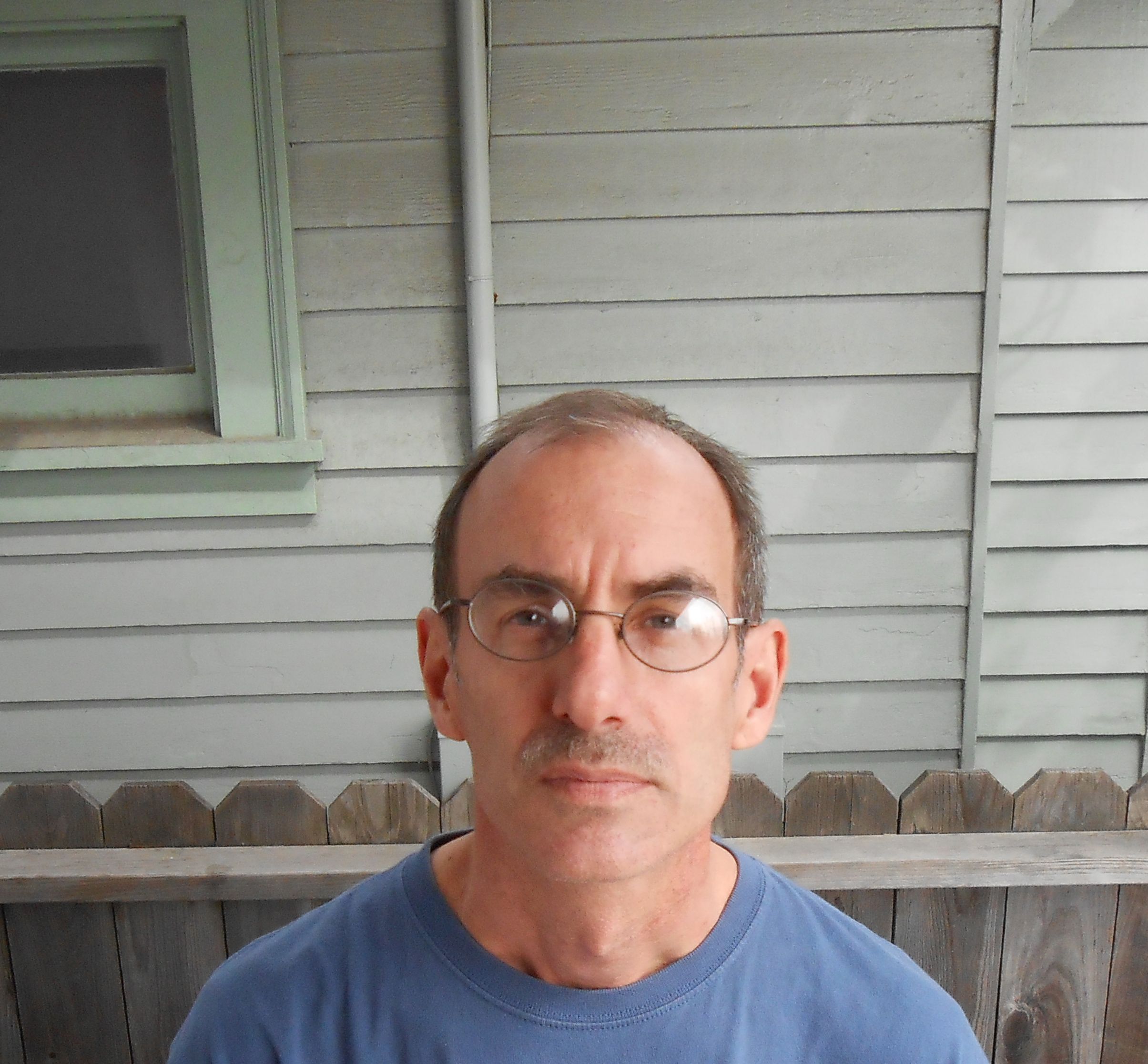

George was one of the neighbors. Gonzalo had watched him coming and going. There was something about him, something solitary and strange, something that made Gonzalo want to buy him an ice cream and ruffle his hair, despite the fact that Gonzalo was sixteen and George was probably three or four times Gonzalo's age. It was hard to tell these days.

It'll be ready by morning, Philip promised. The foot.

Philip tinkered with the lumpy thing floating in its vat of blue liquid, the blob of flesh and wires that was supposedly going to enable Gonzalo to walk again. It looked more like a root vegetable than a foot.

Who is Zeke Yoder? asked Philip.

Zeke Yoder? How do you know about Zeke Yoder?

Philip shrugged.

You were talking about him in your sleep.

Philip went back to the blobby foot as if he didn't really care about the answer. Gonzalo picked a book from his bedside and thumbed through it. It was called Aliens & Anorexia, seemingly another one of Philip's research books about alien abduction narratives of the late twentieth century.

Just like in his dreams, Gonzalo wanted to find a boy and a girl and a garbage dump. He wanted to find a portal. This was his mission, but it was more than that. He needed to find himself or lose himself, to find the heart of mystery or give it up forever, to find love or destiny or annihilation. Why else be alive?

The cottage was full of books, but also maps. Maps of the Arctic Circle, Novaya Zemyla, Iceland and Greenland, maps of Bolivia and Chile, a map of the city of Fez, maps of the Sahara and the Atacama deserts, a map of Madagascar, a map of the Guatemalan jungle and the sites of Mayan ruins, maps of San Diego, the Torrey Pines Reserve, Peñasquitos Canyon and Rose Canyon, Chula Vista and Imperial Beach, a map of North Dakota, a map of Iran, a map of Mexico, a map of Baja California, a map of Tijuana with a smudge of a blank spot of surprising width on the northeastern edge of the city: the municipal dump.

There were odors Gonzalo would never forget. Heaps of trash undulating in the heat. Nothing was stable. Children suffocated sometimes, when the garbage shifted and tumbled on top of them.

It was just before dusk on the day that Disposable Hill rumbled and then collapsed. Manolito screamed. Gonzalo couldn't locate the source of the scream. He was sure that Manolito was buried in the rubble, and he raced through new, mushy paths created by the collapse to find him. Right there in the center, where the hill had once stood, however, was a tunnel sloping down into the earth; it seemed to whirl; it seemed to be rotating; it seemed to be breathing, alternately releasing a cool, fetid wind and sucking air into the depths of the earth.

It seemed to be speaking. Gonzalo stood frozen, trying to understand what it was saying, whether it was the tunnel itself speaking or some creature deep within the earth.

All there is is time, he thought maybe it was saying.

The carnival is never-ending, he could have sworn it said next.

Come, take a ride, he was absolutely sure he heard.

He was terrified. He was six years old.

San Diego was foggy and tropical. Gonzalo had been delirious for weeks now. In that time, San Diego had become the site of a massive government crackdown. Curfews and checkpoints and soldiers everywhere, Philip told him. Gonzalo would watch enormous machines glide through the sky; the sky itself was the color of a machine that might travel into space. Gonzalo had nothing much to do except stare out the window at the sky and the occupants of the other cottages as they came and went, while Philip tinkered with the foot. All of the cottages were occupied except the one next door. It had burned in 2022, and had been boarded up ever since.

Leahbelle was out there somewhere. All Philip had been able to tell him was that she hadn't returned to the camp in the cactus garden. Gonzalo's motorbike was still there; nobody had bothered it.

Gonzalo wondered if the motorbike was under surveillance.

Gonzalo's palm tingled. He looked down, and where the digital readout would have normally told him the time and temperature, there was a message: I'll get the motorbike for you—Eeshoo.

This message from his virus was disturbing on several levels.

You can read my thoughts? Gonzalo asked.

Gonzalo's palm tingled again.

Your thoughts are mine, too, it said.

While Gonzalo was trying to figure out what that meant, and trying to figure out just how violated he should feel by this invasion of his mental privacy, his palm tingled again.

Your thoughts and feelings are like my atmosphere, it said. I breathe your thoughts and feelings. I can't separate them from myself.

Philip was doing something to Gonzalo's foot with a tiny drill the size of a toothpick. There was a smell of burning plastic. His palm tingled.

For example, I'm in love with Zeke Yoder, too, Eeshoo said, even though I've never met him.

Gonzalo blushed.

Well, it wasn't like it was a secret from anyone but Zeke. Probably even Leahbelle had figure it out, just before the bomb hit. It was just about the saddest thing that had ever happened to him, Gonzalo thought.

Just you wait, Eeshoo told him. Things can get a whole lot sadder than that.

And now this.

I can't live this way with you, Gonzalo thought.

You'll have to, said Eeshoo. We're symbiotic.

Gonzalo's sleep regulators had been damaged in the explosion, so Philip gave him something to help him rest. He dreamed, but couldn't remember anything when he woke. It was the middle of the night. He was sure that he heard someone or something moving around in the vacant cottage next door.

He hobbled to the window. His palm tingled.

Too big to be rats, said Eeshoo.

Big enough to be people? asked Gonzalo.

Just the size of a nightmare, said Eeshoo.

A couple of creatures, defying the curfew, strolled through the courtyard. They paused to fondle and kiss. It was so dark that Gonzalo couldn't tell what kind of creatures they were. They reminded him of his family, maybe because they were dimly lit shadows themselves or maybe for some other reason he couldn't make sense of, buried in the back of his mind.

Gonzalo's memories of his mother were dim, and he wasn't even sure what other family members he'd had back there in Tegucigalpa. There was a room and a door that led to another room and several people, some of them children. Brothers and sisters or just roommates? He could remember the terror of electric fences, the buzzing of drones, the explosions throughout the city, but not one human face except maybe, probably, his mother. Her name was Luna, Luna Vega.

He had no idea why he left when he was five, whether he left freely or was taken, whether he fled or was sent, whether his mother was alive or dead.

Let's talk about your childhood then, said Eeshoo.

Let's not, said Gonzalo.

He shut off the digital readout on his palm and lay back down. It continued to tingle for a while, but he ignored it, and eventually Eeshoo stopped pestering him. As he drifted into sleep, he thought he heard a tinny little voice saying, I'll find other ways to talk to you if I have to. But maybe it was just a dream or a figment of his imagination.

But somebody or something was definitely banging around in the boarded up cottage next door.

In the morning, Philip gave him a patch on his leg and the leg went numb. The blob actually looked like a foot, and Philip was down there attaching it, while Gonzalo's thoughts raced.

Leahbelle was out there somewhere, on her own. The idea that she might be injured or dead or wandering around insane was too much for him to bear. Zeke Yoder was supposed to have been headed this way. The idea that Zeke might be injured or dead or wandering around insane didn't disturb him nearly as much, and he wasn't sure why. Maybe he didn't believe it. Maybe he loved Zeke, but he didn't owe him anything. Maybe he thought Zeke needed to suffer; maybe he thought his innocence was a kind of force field; maybe he hoped that Zeke had grown desperate enough to need him. The city seemed empty and quiet, but crackling with a lovely sense of dread. The fog had come in and hushed the ominous light with a sultry tropical doom. Why did he love that word so much? Doom.

He felt at home here somehow. So many of the males here were solitary and butch. Like you, he thought. Like me? Am I solitary and butch? Lonesome road, somebody said, or thought. The words appeared directly in front of him as if they were on a screen. So many of the females were coupled and butch. So many of the other-gendered beings were alone and not exactly butch, but sometimes butch, or they moved in and out of groups with boundaries that were always shifting, and who knew what sort of identities they had?

Gonzalo had tried a lot of things out. Still, he was usually alone with his own thoughts, whoever else was in the vicinity. Not anymore, said words on the imaginary screen, and he heard them at the same time.

The foot was done.

As soon as the anesthetic wears off, you could try to walk on it, Philip said.

How long?

Give it fifteen minutes. Don't walk too much, Philip said. Take it easy.

Gonzalo put on some sunglasses, grew some fake hair, and limped into the courtyard. The foot felt okay. He found a board that had been partially pried off the burnt-out cottage, just enough to squeeze in through the broken window. It was dark inside, light only coming in through cracks in the boards and around the edges. It smelled of smoke. He recalibrated his visual mechanism to better see in the dark and paused to let it take effect.

The cottage was charred and empty, with the exception of a small flexi-screen stuck to the wall with living jelly.

If you got a connect, tell them i'm looking for a computer. Tell your connect this guy was making me one but got pulled into the vortex of his own past present and future. It had its own hologram world and you go to new presentation and type in what you want and it would happen. Tell your connect i'm looking for THAT computer and it comes with a manual. Ask your connects. It would do anything and it came with a manual.The guy looked like a pancake and then he wasn't. It had movie tube so you can watch free movies and the computer girls use it to become the movies they watch and vice versa. Girls use it to time travel and change their eye color. Its like a hologram computer. It can get anything in the world done.

The note itself didn't seem that weird to Gonzalo. The rumors of secret computers that you could use to change the future had been circulating forever and had entered the imagination of the drug-addled and schizophrenic fringe long ago. The only question that bugged him was if the note was directed at anyone who might wander into this charred, abandoned building or whether it was directed at him specifically. If it was aimed at him specifically it meant that somebody knew who he was and knew where he was and at least suspected that he was in possession of the computer that Harta had stolen from her brother before she killed him.

He climbed back outside and limped down to Park Avenue. The abandoned business had once been called The Crypt. The sign, in Gothic lettering, still hung out front. He limped south down Park to the cactus garden in Balboa Park, where he observed his motorbike from a distance. Then he continued through the park and the shantytowns, showing Leahbelle's picture to a few people he knew he could trust based on their underground tattoos or augmentations. By the time he made it back to the cottage, he was exhausted and in pain. He collapsed into bed, feverish again. His body hadn't quite accepted the new foot yet as part of itself. Philip tinkered with the foot, taking suggestions from Eeshoo. He soaked the foot in some sort of chemical wash.

I constructed a primitive robot to retrieve your motorbike, he told Gonzalo. It should be on its way.

What if they're watching it?

It'll park the motorbike by the communal laundry room across the alley out back. Even if its under surveillance, they can't pinpoint your exact location.

Something beeped.

It's back there now, said Philip. We'll let it sit for a day. See what happens.

Gonzalo had more dreams. In the dreams, everything interesting was happening underground. Love affairs and revolutions and elaborate lectures about the future. Gonzalo was taking notes, but when he looked at what he'd written, it was just a blur. Somebody was sitting next to him, a little squiggle of a cartoon, like the old-fashioned microbe emoji. He recognized him right away. Eeshoo winked at him and Gonzalo woke up.

It was late morning. Philip was watching some ancient film and taking notes.

The UFO Incident, he told Gonzalo. A seminal text from 1975. It marked a shift in alien abduction narratives, a shift that dominated the form for decades.

How's that? asked Gonzalo.

The idea of lost time, of an alien interest in human reproduction, the image of the "Grays," large-eyed creatures who were half surgeon, half neutered baby. This was a marked shift from the aggressive or benign invaders of the 1950s whose concern was primarily nuclear technology.

Philip grew increasingly fervent as he expounded on his research.

The genetic engineering craze of the twenties changed everything, he said. During the "phantom twin"epidemic, the idea took hold that there was another dimension, an exact replica of ours, and that our doppelgängers were invading from there. More and more, people experienced their phantom twins as alien torturers. Meanwhile, as we began to visibly mutate, so did our aliens. The idea of a more evolved species that was static and big-eyed seemed quaint. The idea that the form of the Grays was a kind of conformist costume over infinitely varied bodies underneath couldn't save the image. More and more, the images of the aliens resembled images of our own species a few years in the future.

Gonzalo's hand was tingling.

Have you checked out the motorbike? he asked Philip.

I was going to, said Philip. Came across a dying rat back there by the recycling bins. Gave me the creeps.

A dying rat.

Looked at me with those little eyes. So sad, like a little furry man. One of the feral cats must have mauled him. Maybe you should move him to a safe spot so he can die in peace. Or put him out of his misery.

Him, said Gonzalo. How do you know it's a male?

Awful big rat, said Philip.

Gonzalo had a bad feeling. He set it aside for the moment.

What if there is another dimension? he asked. Not an exact replica, but another world interwoven with this one. With portals that can take you back and forth.

The portals, of course, said Philip, and he waved his hand as if it was irrelevant.

Gonzalo limped out the back door of the cottage into the alley behind it and looked around. Some sort of mutant was digging through the recycling dumpster, cursing and laughing.

What is it? he asked Eeshoo.

Turn the readout on, said a voice in his head.

Gonzalo waited until the mutant had finished collecting the scraps he wanted and wandered further down the alley, and then edged over toward the dumpster. He could see it already from some distance, a grayish shape that was visibly alive sprawled next to the door of the laundry room. Its little foot was twitching.

It was definitely too big to be a normal rat. It was looking right at him as if it recognized him or had a message for him. It was clearly dying, but there wasn't any blood or obvious wound that Gonzalo could see. It looked kind of peaceful.

Gonzalo had seen people die before.

Did you come to find me? asked Gonzalo. Did Pazuza send you?

The rat just stared at him. He couldn't tell if it understood or if it was already beyond understanding.

He turned his digital readout back on.

Pick it up, Eeshoo told him. Hold it for a minute.

Gonzalo cradled the rat in his hands. It had the sweetest face and it looked at him with such a great sadness and a sense of peace. He could feel it breathing. He could feel its little heart beating.

He felt something else, as if some slight energy was passing between the dying rat and his hand. The rat closed its eyes. A moment later, it was dead.

Gonzalo thought he should bury it or something.

Just leave it, said Eeshoo. Something will eat it.

What happened? asked Gonzalo.

I helped it die, said Eeshoo. And I found out why it was here. You've got to get out of here.

Now? said Gonzalo.

Now.

The motorbike was out of the question. Better to catch a ride with George, said Philip. I'm sure we can work out a trade.

A trade, thought Gonzalo, and for a moment he wasn't sure if the phrase came from himself or from Eeshoo, if the image of all the things one might trade to another creature came from himself or from Eeshoo. Food, sex, drugs, ecstasy. Shelter, medicine, tenderness. You could trade a performance or a song, an animal or a child, a virus or a ride. Like so many times in his life, Gonzalo had nothing to trade but his charm and his willingness to take risks other people wouldn't want to. His charm, he thought, but again he wasn't sure if the sarcasm was his own or Eeshoo's.

Now that he was leaving, San Diego seemed the most beautiful place, and he didn't want to go.

George picked him up on the corner. The truck was as ancient as his motorbike. An off-Grid vehicle, it ran on gas. Gonzalo didn't ask where George got the gas.

George was old, totally old, old enough to be Gonzalo's grandfather, but looked more like he'd be Gonzalo's older brother. It was more than the usual chemicals, processes, and genetic alterations that kept his hair black and lustrous, his skin smooth and shiny, and his eyes focused. He didn't have that aura of artificial wonder, the telling loss of interest, the forced chatter about the most recent cultural artifacts. He really seemed like a slightly crazy little boy, a boy with a good heart who was still trying to make sense of the bewilderment life had presented him.

By the time they'd driven the city streets south through downtown and the Logan Barrio into National City, it was clear that George's bewilderment primarily concerned his daughter Violeta. George had been devoted to Violeta, although he and Violeta's mother had grown to dislike each other intensely. They'd separated when Violeta was young, and Violeta was stuck in the middle of their disputes forever after. When she was nineteen, Violeta disappeared.

Well, of course I still knew more or less where she was, George told Gonzalo. She was still connected to the Grid, and I could usually pay the fees to pinpoint her location. Portland, Vancouver, Billings. Then south to El Paso and across the border. I lost track of her while she was in Mexico. Then suddenly she was in Iowa City, and she gave me a call.

Iowa City, said Gonzalo. I stayed around there for years.

George didn't seem to hear him.

Dad, she said. It's me. She told me that she missed me. I guess I cried, said George. I didn't understand it. Why wouldn't she come home to San Diego?

The streets of National City were immersed in a bluish fog that seemed to seep out of small holes along the curbs. Nobody walked the streets.

Gonzalo's palm tingled. He'd forgotten to shut Eeshoo off. They drove in silence.

Gonzalo thought that you had to allow for silence, whenever it happened. There was so little silence. Not enough silence.

Quiet men, thought Gonzalo. What was it about quiet men?

Then she disappeared, said George finally. Really disappeared. Vanished without a trace.

It was almost impossible for a living person to vanish without a trace. Gonzalo kept this thought to himself.

That was ten years ago, said George. I'm sorry, she said, but she knew where things were headed and there was nothing to be done about it.

She knew where things were headed?

She was a special girl, said George. She could see things sometimes. She knew things ahead of time.

She could see different paths through time, suggested Gonzalo.

Different paths or just one, said George. I don't know.

There's a checkpoint up ahead, said Gonzalo.

No worries, said George. It's my cousin.

It was a young guy with buzzed hair and bright blue-gray eyes. Gonzalo smiled and he smiled back, and then he chatted with George about various family members on this side of the border and the other, and then he said, I'm here until five today, and then he smiled at Gonzalo again.

They drove a few more blocks, and George pulled over in a motel parking lot.

We've got to wait a half hour, he said. They shut down the checkpoint at Plaza and L and move it to Palm. That's our opportunity.

They're short-staffed, said Gonzalo.

It's a leaky boat, said George. No way to plug all the holes. We shoot down L to Sweetwater then out east and through some old parking lots south to E Street. Chula Vista's easy. They move the checkpoints to keep people off guard, but of course I've got inside information.

Your cousin, said Gonzalo.

I'd stay away from that one, said George. Nothing but trouble.

Gonzalo wondered if his attraction was that obvious. But maybe the cousin was the obvious one.

He might show up here in a minute, said George. If he liked your face enough, and I'm pretty sure he did.

What did Philip tell you? asked Gonzalo.

Nothing. It's better that way. I don't need to know why you want to cross.

Okay, good.

Lots of people want to cross. Why wouldn't they? Nothing but poverty and war here. Make your way to the land of opportunity.

There was a bitterness in George's tone that Gonzalo thought was related to his daughter.

What was she doing in Mexico? he asked.

Making her way in the world. Smuggling, I think. Here he is, said George.

Sure enough, there was his cousin, heading toward them across the parking lot.

He stood outside Gonzalo's side of the truck just grinning. Gonzalo wondered if he should be suspicious or afraid. Really, wasn't this cute young guy his enemy?

I wanna show you something, the cousin said. In the storeroom.

The storeroom.

The motel's storeroom. I've got a key.

We have to go soon, said Gonzalo.

We've got time.

The storeroom was full of spare towels and hologram converters. It was cramped, but that wasn't a problem. They were both flexible and accustomed to fitting in small spaces when they had to. Gonzalo knew how the cousin would like it, he didn't even have to ask. When they were done, Gonzalo lit up a cigarette. The cousin laughed.

You really are a rebel, he said.

This is the only time I do it, said Gonzalo.

Like most of us.

The cousin took the cigarette from him and took a puff.

Don't you get tested?

Sure, but they don't care about traces of nicotine.

What's your name anyway?

Alex.

Gonzalo was aware of the time passing, and that he would most certainly never see Alex again. He felt a strong affection and a certain hostility, and a need to make some sort of contact, no matter the risk.

How can you work for them? he asked.

You see how it works, said Alex.

No, I don't get it.

I mean it's not just my job. George makes his living, too. Other family members, and the traffic just keeps moving. We're all working on the same side, really.

Not true.

You want to be my enemy.

The government's really killing people. Real people, real death.

Is death real?

Gonzalo couldn't quite keep track of everything he was feeling. It was as if everything had dissolved and was still dissolving, and he knew that he could just let it go: the things he believed, the stories he told himself about who he was and what he was doing. He could sense Eeshoo judging him. Judging him how exactly he wasn't sure, but definitely judging him. Maybe his virus was a romantic. Maybe Eeshoo thought he was betraying his love for the pure and innocent Zeke Yoder by hooking up with Alex.

The singularity's gonna destroy all of us but the rich, Gonzalo said.

You gotta see the big picture, said Alex.

I see the big picture. The picture I see is huge.

Death isn't real, said Alex. Death doesn't matter. Death is like the goal.

Gonzalo had always been immersed in these conversations. He'd been born inside these conversations, he was pretty sure, and he wasn't sure if he needed to break out or tunnel deeper inside to figure out what was real or what he should bother doing in time and space.

Kill yourself if you want, but don't kill me, he said.

The idea is to burn and blacken the planet, said Alex. Burn it up on our way out, so that a new form of consciousness can emerge from the ruins. This is a chrysalis. This is just an egg. What comes out of that egg is the real singularity, and none of this revolution shit is slowing down that operation one tiny bit. The Grid doesn't matter.

Alex leaned in and kissed Gonzalo hard, then stepped back and laughed.

It's alchemical, he said. This shit-hole is nothing special. This shit-hole is fuel.

Gonzalo figured that most people only believed in the things that excited them. He wasn't sure about himself.

It's Earth, said Gonzalo. It's home. It's my home.

Oh yeah? Some home. You like it here? For real?

In this storeroom? said Gonzalo. Sure. But it's time for me to go.